12 Best Ways To Use Koji

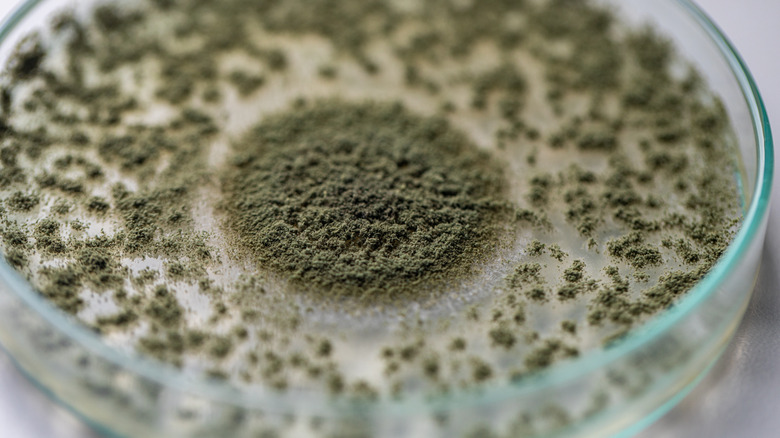

You know koji; you just don't know you know koji. Koji is a strain of a fungus called Aspergillus oryzae, and it's used for many different culinary purposes ranging from marinades and sauces to alcoholic beverages. If you have soy sauce in your kitchen, you have koji in your kitchen. If you have miso in your kitchen, you have koji in your kitchen. If you have mirin or sake or many other common beverages or condiments that trace their origins back to Japan, then you already are familiar with koji. There are even koji-based charcuterie boards.

Now you just need to learn how to use koji in your kitchen. To do so, it helps to understand what it is that makes koji so good. As KQED explains, the answer is one word: umami. Per Modern Farmer, koji bumps up the umami in whatever it touches and makes everything taste even more like itself. As the New Gastronome says, koji effortlessly elevates food. It's almost like cheating, only it's not.

Dry-age beef with koji

With all the well-justified focus on the freshness of ingredients in our cooking, it would not be out of line to ask why anyone would want to age beef in the first place. It's a good question to which there are good answers. The reasons we dry-age beef — and the reason dry-aged steaks are more expensive — are twofold: a deeper flavor and a more tender texture.

Dry-aging beef is a similar process to that used in aging a good cheese. As explained by Steak School, large pieces of meat are left in a carefully controlled environment to pull moisture out of the meat and allow bacteria to form in such a way as to render the flavor profile of the beef more robust. It is, essentially, a controlled decomposition that occurs over the course of weeks or months.

It is possible to dry-age beef at home, but it takes both a lot of time and, as Art of Manliness points out, a lot of work. Fortunately, though, koji can ride to the rescue. As Popular Science explains, rub a steak with crushed rice koji — which can be purchased at almost any Asian (but particularly Japanese) market — and in two days, the powerful enzymes in the koji will tenderize the meat, turning it into something that has many of the qualities of a steak dry-aged for 45 days.

Marinate proteins and more in koji

One of the easiest ways to start your koji journey is to use it as a marinade. Shio koji is just rice koji from your local Asian market mixed with salt and water then left to ferment for a week at room temperature. Or you can buy prepared shio koji.

Shio koji is an excellent marinade for just about any protein. An hour-long marinade for beef is good, but three to four hours is better. Shio koji shines on chicken, whether thighs, breasts, or a whole bird, though soy-based shoyu koji makes for a great brick chicken. Shio koji may be at its best, though, with seafood. Shio koji on steelhead trout brings out the fish's natural sweetness. However, it has an entirely different effect when used as a marinade for grilled mackerel, taming the naturally aggressive flavors of the fish. Or marinate sea scallops in shio koji, searing them with butter and then pair them with a ginger-scallion sauce.

But it's not just proteins that benefit from spending some time up close and personal with koji. As noted by SFGate, mushrooms are already high in glutamate (as in the MSG component), and that makes them a nearly perfect candidate for a koji marinade, whether with shio koji or using miso. A quick trip to the grill and those little doubled-down umami bombs could either be the star of your meal or a very worthy side dish. Much the same could be achieved by cutting firm vegetables like broccoli, sweet potatoes, or even eggplant into bite-sized pieces, marinating them in koji, and skewering and grilling them.

Swap koji for soy sauce in your stir fry

Stir-frying is a Chinese-based cooking technique that has become something of a dish (or class of dishes) on American shores. The basic parameters of the dish as well as the technique are fairly well understood. As Cooksmarts explains, stir-frying is typically done in a wok over high heat with a small amount of oil. One key, per Better Homes & Gardens, is that the vegetables and proteins need to be cut into evenly tiny-sized pieces so they cook at the same rate.

Another critical element of stir-fries is the stir-fry sauce. Typical stir-fry sauces tend to include soy sauce, chicken (or vegetable) stock, aromatics like ginger and garlic, oil (often including sesame oil), vinegar (often rice vinegar), a sweet element (like sugar or honey), and sometimes a heat element (like chili garlic or sriracha sauce). But stir-fry sauces are more a theme upon which there are many variations than they are recipes written in stone.

Any stir fry sauce using soy sauce necessarily involves koji since soy sauce is made using koji. But to take your stir fry to the next level, exchange koji — whether shio koji or shoyu koji — in place of the soy sauce in your stir-fry sauce. Doing so can only boost the umami deliciousness of the dish.

Serve amazake

When most Westerners think Japanese beverages, it is probably sake, a rice wine, that first comes to mind. As Japanese Food Guide points out, though, perhaps amazake should be up there too. This low-alcohol, or even entirely non-alcoholic, beverage dates back many centuries. Amazake really took off in the Edo period (1603-1868) and is now known as a "drinkable IV."

Like sake, amazake is made from fermented rice. But unlike sake, as Japanese Sake explains, amazake has a porridge-like texture and a minuscule alcoholic content that maxes out at about the level of Western non-alcoholic wines. Amazake is generally made in one of two ways. Koji amazake is made directly from rice koji as-is and is non-alcoholic. But amazake can also be made from sake lees, the leftover by-product from the brewing of sake, as Kokoro explains. This method still results in amazake generally having an ABV of under 1%.

The flavor profile of this twist on sake is distinctly sweet and refreshing. And yet, because amazake is created through fermentation, it has the complexity of an alcoholic drink without the buzz. It is precisely that — the pleasant sweetness combined with the complexity of flavor and the non-alcoholic properties — that makes amazake such an attractive alternative to sake.

Use miso to flavor proteins

Likely one of the most familiar uses of koji is to make miso. Miso is a paste of koji, fermented soybeans, salt, and water. There are, generally, three types of miso (and variations of those): white, yellow, and red. The most popular and common type of miso is the white version, also known as "shiro miso." Yellow miso, also called "shinsho miso," is shiro miso's nuttier cousin. Red miso, or "aka miso," has both a deeper color and a stronger flavor.

While it is possible (indeed fairly easy but very time-consuming) to make miso paste, many store-bought versions are both excellent and easy to acquire and use. Miso, like other types of koji products, can of course be used as a marinade, as in this miso salmon. Slathering miso on proteins is rarely a bad idea and, quite to the contrary, is one of the best ways to amp up their umami.

But miso can also be the vehicle of the cooking itself. In this braised pork belly salad dish, for example, the red miso in all its glorious funkiness is the star ingredient in the braising liquid. Much the same could be done with beef short ribs or oxtails. Indeed, as Know Your Pantry suggests, perhaps there is no better way to cook tofu than to braise it in an umami-rich miso broth.

Create miso soup

The introduction to the world of miso for many, if not most, of us is miso soup at our favorite Japanese restaurant or sushi bar. Miso soup consists of miso paste, tofu, seaweed, and dashi broth (the basic stock of Japanese cuisine). Today, three-quarters of the population of Japan consumes miso soup at least once a day, according to Wa-Shoku.

The origin of miso soup goes back to the introduction of hishio, a soybean and salt concoction, into Japan by China during the Asuka period (A.D. 592-710), per Kokoro. The Japanese subsequently developed hishio into a paste, though it would not be until the 12th century that monks embraced miso paste and mixed it with broth to make the first miso soup, as explained by Sky History.

Like much of Japanese cuisine, miso soup is a wonderfully, elegantly simple dish. Its five ingredients combine over low heat — once miso is added the soup it should not be boiled because it destroys the aromatic qualities of the miso itself — to create a simple, elegant, and subtly but deeply satisfying soup. While miso soup is nearly an essential ingredient in Japanese meals, it can also be a great, quick pick-me-up of a midday snack.

Try a miso cheese

Many vegans say it isn't meat they miss most, but rather cheese, per Vegan Food & Living. There are nut "cheese" products out there, but to many, they make a poor substitute for the real thing. Perhaps they would be better off looking to an older tradition.

According to Soyinfo Center, the Chinese have been fermenting tofu since at least around 1600, as indicated by written references. By the late 1800s, fermented tofu was being made in San Francisco, according to Live Kindly. As Soyinfo Center also points out, fermented tofu was first referred to as "fermented cheese" in a British patent by Li Yu-ying of France.

Making fermented tofu cheese, also known as misuzake, is not difficult, but it is not done quickly. To make misuzake, you need to press a wrapped block of fresh tofu under a heavy surface for about two hours. While the tofu is pressing, mix some miso (and thus koji), vinegar, and sugar. Once the block is pressed, coat the tofu in the mixture and then transfer it to an airtight container slightly larger than the block of tofu itself. Place the container in the back of a refrigerator for at least one week and up to three months.

If the process of making fermented tofu yourself is more than you want to take on, there is no shortage of excellent fermented tofu cheese products out there. Numerous fermented tofu products can be found in most Asian food markets. Try the chili-spiked Chinese version in your next stir-fry.

Make a compound butter with koji

One of the easiest ways to go about elevating even the humblest of dishes is to make a compound butter. It sounds fancy but is incredibly simple. It is, basically, nothing more than flavored butter. To make compound butter, you just whip a flavoring ingredient into softened butter. That flavoring ingredient can be either savory or sweet. Perhaps most classically, it's herbs, lemon, and garlic or shallots.

But the flavoring ingredients can be more complex than that. Ed Lee of 610 Magnolia in Louisville, Kentucky, makes a compound butter flavored much like his kalbi sauce by mixing together soy sauce, sugar, and sesame oil and combining that with garlic, ginger, scallions, and chile flakes as well as softened butter in a food processor to make logs of Korean barbecue compound butter. Just pop this compound butter on a steak or, as Lee does, roasted vegetables.

Compound butter can be a perfect vehicle for the umami flavors that koji and koji-containing products can bring to the party. Shio koji butter would be perfect on a steak. Or try elevating grilled corn with miso butter.

Use koji as a rub for meats

While koji, whether shio koji or shoyu koji, makes for an excellent marinade, koji in other forms can be a great rub for proteins. Indeed, rice koji, perhaps the most basic form of the stuff, can be the cornerstone of an easy and excellent rub for all sorts of different meats. Toss some rice koji in a high-speed blender or food processor (or, in smaller batches, even a spice grinder) and process it to a smooth grind. Rub a steak with the ground rice koji and refrigerate the meat anywhere from overnight to 24 hours. Season the steak with salt, and it is ready for the cast-iron pan, a grill, or your sous vide setup.

Or process the rice koji, salt, and some pepper to a rub. Take a whole chicken and gently separate the chicken's skin from its flesh. Working gently to avoid tearing the chicken's skin, apply the koji rub under the skin and refrigerate overnight. Remove the chicken from the refrigerator and allow it to sit at room temperature for an hour before roasting the bird.

A similar process works well with pork chops. After rubbing the chops with the ground koji, let the rubbed pork chops cure in the refrigerator for three to five days. Rinse koji from the chops and season them with salt and pepper before cooking on the stovetop, grill, or sous vide.

Bake bread using koji

Quite possibly one of the least intuitive applications for koji in the kitchen is bread making. And yet koji is indeed useful in that ancient craft. According to Sourdough Companion, while koji is not used directly in the bread making process, it's used to create sakadane, which has seen use as a bread starter for as long as bread has existed in Japan.

Bread made using koji tends to have some of the characteristics traditionally associated with sourdough. Amongst these are a cheese-like smell and moister crumb, per Controlled Mold. The Koji Fermenteria describes the flavor of koji sourdough bread as somewhat akin to sake.

There is more than one way to use koji in bread baking. For example, you can use amazake to enrich sourdough bread or rye bread. Similarly, you can use shio koji to replace salt in the bread, resulting in a softer interior and crispier exterior.

Turn up the heat with gochujang

Koji is, perhaps, most closely associated with high-end, world-class chefs pushing the envelope of cuisine and, of course, with Japan and Japanese cuisine. But don't sleep on Korea. Korea's gochujang could be described as miso's slightly sweet and angry cousin. It is a chile paste made with, amongst other things, gochugaru (ground red chiles), glutinous rice, barley malt powder, and (as the National Institute of Health points out), koji.

Gochujang is as essential to Korean cuisine as miso is to Japanese. Indeed, Fine Dining Lovers lists gochujang as an essential ingredient for a Korean pantry. It's also been called the Korean version of sriracha. Gochujang is an essential ingredient for many, if not most, components in Korean barbecue, perhaps most notably bulgogi. It is also often an ingredient in the marinade for galbi as well as banchan, that spread of "side dishes" that accompanies just about every Korean meal (per The New York Times). Kimchi fried rice is a classic Korean home for gochujang.

While the world of classic Korean cuisine is replete with dishes including (if not built on) gochujang, it can be used in any number of non-traditional ways. For example, spike mayonnaise with gochujang and pop it on a burger or use it in a lobster roll. Consider making a Korean hot chicken sandwich (think Nashville hot chicken with gochujang). Or you could make your Sunday brunch better by using gochujang butter in the hollandaise sauce for your eggs Benedict.