10 Times Coffee Was Banned Around The World

Let's face it — it's hard to imagine a day without coffee. It starts the morning off right and gives that boost many people need to start their day. And with so many different types of coffee available, our caffeine fix has endless possibilities.

No one knows when coffee was first discovered, though there is a legend about a goat herder in the Ethiopian peninsula. According to the National Coffee Association, the story goes that Kaldi, a goat herder, saw his animals eating berries that kept them up all night. He told a local abbot of his discovery; the abbot brewed a drink from the berries. To his surprise, the drink gave him the energy he needed to stay alert through his long evening prayers. He shared the drink with the other monks, and tales of the miraculous drink began to travel.

While the legend is probably just a good story, the National Coffee Association says coffee was cultivated, traded, and enjoyed in the Arabian peninsula by the 15th century. By the 16th century, coffee made its way to Persia, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey. It was brought to Europe and America (then still under British rule) in the 17th century, where it quickly grew in popularity.

Despite this worldwide love for "the wine of Araby" — or maybe because of it — rulers throughout history have attempted to ban coffee, coffee houses, and the trade of coffee beans. Lucky for everyone, none of those bans worked or lasted very long.

Mecca (1511)

An article in Business Insider says that in the early 16th century, Sufi Muslims drank coffee, which they called "qahwa," to help them stay away during evening prayers. Coffee houses, known as Kevah Kanes, opened shortly thereafter, giving men a place to gather and talk (via the Kent & Sussex Tea and Coffee Company). Some of what they spoke about encompassed politics, which didn't sit well with a governor of Mecca named Khair Beg.

In 1511, Beg closed all coffee houses and imposed severe physical punishment on anyone caught selling or even drinking coffee. But the ban didn't even last the year. The Sultan of Cairo, Al-Ashaf Qansuh al-Ghawri, was a coffee drinker himself. At that time in history, Cairo ruled over Mecca, and the sultan overturned the ban. In fact, he did a little more than that, at least when it came to Beg himself. In 1512, Beg was found guilty of embezzlement. The sultan put him to death.

Mecca (1535)

Many types of Middle Eastern java, such as Khawlani coffee, have been cherished for over three centuries. But that didn't stop the people in power from trying to ban it again. The death of Khair Beg didn't fix coffee issues in Mecca. In 1535, another attempt was made to ban the drink. This time, it wasn't about politics. It was about religion. Coffee houses originally began as places for religious meetings and conversation. But religion wasn't the only topic of those conversations. The men who gathered there also discussed philosophy and politics. Muslim clerics weren't exactly pleased about that.

Islamic law, sometimes called Hanafi Law, was the rule of the land, as it still is in some parts of the Middle East today. At the time, coffee might have been subject to a bit of a translation problem. In the fifth chapter of the Quran, the sacred book of Islam, verse 90 forbids the drinking of "intoxicants." In 1535 Mecca, some Muslims believed that coffee was an intoxicant, just like alcohol. Thus, they tried to ban it under religious law. But their efforts failed. Coffee continued to be enjoyed in Mecca and would soon make its way to the rest of the world.

Turkey (1536)

The Middle East was very proprietary about its coffee. After all, that's where the cultivation and trade of it began. During this time, the Ottoman Empire ruled from over the Middle East. The realm was sometimes called the Turkish Empire, and the powers that be were not about to let the world forget why it was considered such a kingdom. Why would they, when Turkish coffee tastes so good?

In 1536, according to an article in the New York Times, the Ottomans wanted to keep a very tight grasp on coffee and its commerce in particular. At the time, the still-new coffee trade represented a large portion of the Empire's income, and they wanted to have a monopoly when it came to coffee trees. So, the government outlawed the export of fresh, fertile coffee berries from Yemen, where the trees were grown. All harvested berries — coffee beans are actually berries — had to be either partially roasted or steeped in boiling water. By doing this, the berries couldn't be germinated outside of Yemen. The plan worked, too. The export ban lasted until the 1600s.

Rome (1590s)

Coffee and Italy are very intertwined. In fact, Italy is so proud of its coffee that it wants Italian espresso to be given UNESCO status as a symbol of Italian heritage. Surely, the Italians would never ban coffee! Maybe not now, but in 1590s Rome, some religious Italians gave it a try. Good thing Pope Clement VIII was around to keep it from happening.

When Clement was Pope, members of the Papal court wanted him to condemn the beverage. They called it "Satan's Drink" because of its origins in Islamic countries. Legend has it that Clement refused to do so until he tasted the diabolic brew. Popular religious website Aleteia explains that things didn't quite go the court's way once Clement had a taste. It's said that his response was, "This Satan's drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it!" Legend has it that the Pope even baptized the beans, cleansing them of any demonic influence.

Constantinople (1633)

Sultan Murad IV believed there was a real danger brewing in the Ottoman Empire, right in the capital city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). Apparently, coffee was contributing to social decay and transgression, and the Sultan wanted it stopped.

The story, according to Atlas Obscura, is that Murad had a problem with public coffee drinking and coffee houses. Like other rulers before and after him, he believed that coffee houses were dens of sedition and dangerous talk. He also knew that members of the Janissaries, a military group that deposed and murdered his brother, gathered in coffee houses. So he decided to put an end to it. A very final end, according to NPR.

National Public Radio tells us that the Sultan declared that anyone found publicly drinking coffee was guilty of a capital offense. That's right. Drink coffee, and you were sentenced to death. It was even said that he was so serious about this decree that he would sometimes even disguise himself as a commoner and wander the nighttime streets of Constantinople while carrying a 100-pound broadsword. If he found a coffee drinker, he'd behead them on the spot.

Surely, his successors were more reasonable, right? Well, not exactly. After Murad IV died in 1640, public coffee drinking no longer resulted in immediate death. First-time offenders merely received a light beating by cudgel, while second-time offenders were reportedly sewn into a leather bag and tossed into the river.

Sweden (1746 and 1756)

World Population Review shows that Swedes are some of the world's highest coffee consumers. It wasn't always this way.

The first Swedish coffee ban was more of a dramatic increase in costs. In 1746 King Adolf Frederick put out a royal proclamation on "the misuses and excesses of tea and coffee drinking." He imposed heavy taxes on both beverages while claiming he was protecting his subjects from caffeine's allegedly dangerous effects.

Per Scandinavia Standard, Adolf's son went further than his father. In 1756, under the rule of Gustav III, banning coffee to protect people's health popped up again. This time, however, it wasn't a simple ban. Gustav III hated coffee and was convinced that it was unhealthy. To convince Carl Linneas (a coffee lover and botanist now known as the father of taxonomy) of the ill effects of coffee, Gustav began what could be considered Sweden's first-ever clinical study (via the National Library of Medicine).

The king took two twins already condemned to death and gave them a choice: die as planned or be part of his "study." He ordered one twin to drink three pots of coffee daily for the remainder of his life. The other twin was made to do the same, but with tea instead of coffee. The king also had two Swedish physicians monitor the health of each. The twins actually outlived the doctors and the king, and the tea-drinking twin predeceased the coffee drinker.

Prussia (1777)

Let's travel east from Sweden and visit Prussia in the 18th century, under the rule of Frederick the Great. Ironically, Frederick did not think coffee was great. But, says the National Coffee Blog, he definitely loved beer.

In order to convince everyone of the merits of beer, Frederick issued an edict in 1777 (via Mental Floss). In it, he stated that he was "disgusted" with his subjects' coffee drinking, as well as how much it was costing Prussia — coffee being an expensive import. Rather, the edict stated they should be drinking beer. After all, "His Majesty was brought up on beer, and so were his ancestors, and his officers." He claimed that battles were won with beer, while coffee-fueled soldiers were less likely to endure the hardships of war or beat Prussia's enemies.

He even wrote to his friends about beer's superiority. In a 1779 letter, Frederick again extolled the virtues of beer and the beer soup he was raised on, insisting that his subjects "can also be brought up nurtured with beer-soup. It is much healthier than coffee."

Frederick's claims of health aside, the more likely reason for his ban was financing. Importing coffee was costly, while Prussian-made beer was cheap. He made coffee roasters apply for a special license, then rarely granted said license. He even hired soldiers to literally sniff out unlicensed roasters. Ultimately, coffee prevailed. When Frederick died in 1786, all restrictions were lifted, and Prussia could once again enjoy its coffee without concern.

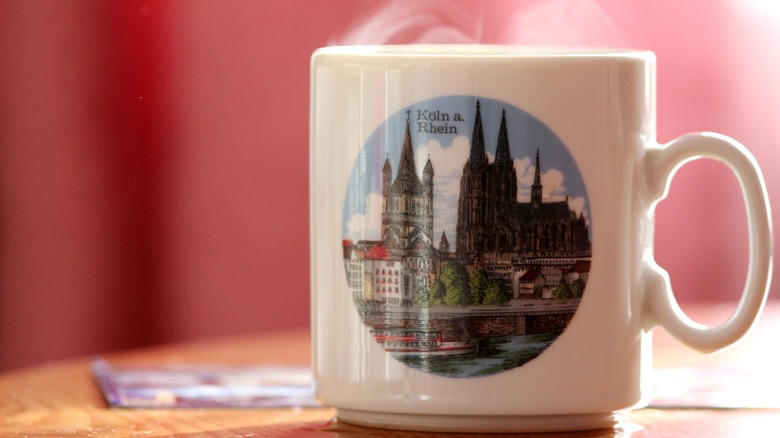

Cologne (1784)

In 1784, news of Frederick the Great's ban on coffee reached the ears of another Frederick, this time a German one: Maximilian Frederick of Cologne.

Possibly inspired by Prussia's coffee ban, Maximilian decided to enact his own. According to the book All About Coffee, Maximilian issued a manifesto on February 17, 1784. In it, he expressed his displeasure about the "misuse" of what he called "the coffee beverage." Coffee was no longer to be dealt. If anyone was found selling coffee, they would be fined or sent to prison for two years.

It wasn't just individual sellers who had to worry, either. The manifesto declared that all "coffee-roasting and coffee-serving" businesses had to close and that hotels and "coffee dealers" had to get rid of all coffee supplies. Frederick went on to state that people who worked in houses, especially the women who washed and ironed, were not allowed to prepare or offer coffee, lest they be fined. Officials and people who worked for the government were told to "keep a watchful eye over this decree" or else they would be fined 100 gold florins. And if they tattled on a coffee drinker? That's a cool 50 florins for their pocket.

Coffee was only permitted for one's own consumption in 50-pound lots — too much coffee for personal consumption. In spite of all of this, coffee survived in Germany. Then, according to Ukers, coffee "took its rightful place as one of the favorite beverages of the German people."

Sweden (1794, 1799)

Modern Swedish coffee break culture revolves around the tradition of fika, which loosely translates to "coffee and cake break." It's a social thing so popular that some corporations actually mandate fika time. You can fika a few times a day, if you like, as long as you always do it in company. One does not fika alone.

With coffee culture being such an important part of modern Sweden, it's hard to fathom that this same country has tried to ban coffee five times. Already, we've discussed the first and second, but the third attempt happened between 1794-1796. The Swedish government decided that coffee importing and consumption was a problem (again). So they managed another ban. People still worked to sneak in their caffeine fix, however. For example, Swedish newspaper The Local reports that when visiting Sweden, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley was able to relish dinner and, "with some degree of mystery, ... some excellent coffee."

Swedes could enjoy their coffee without issue after 1796 — until 1799, at least. According to the Scandinavian Economic History Review, strict punishments were imposed for those who defied the ban, including publishing people's names in a public paper. But that list might have served a different purpose — helping people make connections. Coffee smuggling was a big business during the bans. Poor women, in particular, were likely to turn to the black market to survive. The people only had to endure this ban for a few years; the prohibition was overturned in 1802.

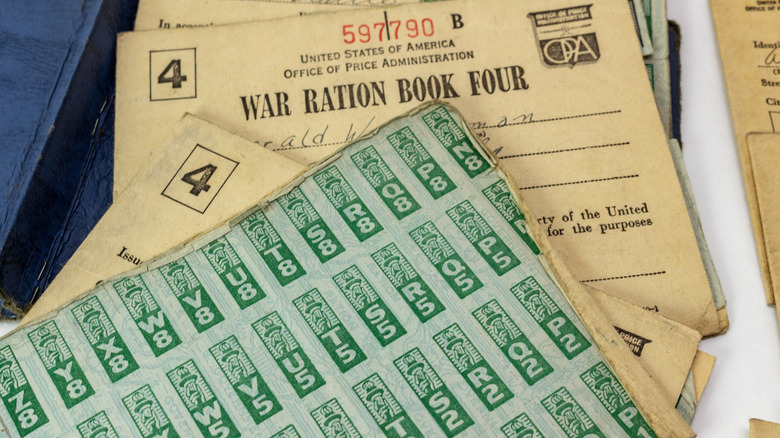

United States (1942)

The U.S. never actually banned coffee, nor did they attempt to. But during World War II, the country definitely had to cut back. And it was because of rationing. Rationing was a way to limit certain consumer goods so important supplies could be conserved. Every American person, including babies, were given points that were used along with cash to buy things like tires, meat, gasoline, cheese, milk, sugar, and, in November 1942, coffee. There was a huge demand for coffee among both civilians and the military. According to The History Channel, rationing was crucial for two reasons: to ensure every American citizen had a fair chance at actually getting the rationed goods and to ensure that priority was given to supplies the military needed during wartime.

The National World War II Museum states that American families were rationed one pound of coffee every five weeks, which equals around 34 cups. Even if people could limit their household to one cup a day, there would still be one day in those five weeks without coffee.

Thankfully, U.S. coffee rationing didn't last long. Things were back to normal, at least when it came to coffee, less than a year later, in July 1943. Hopefully, everybody liked it black, though, since milk was rationed until 1945 and sugar until June 1947.