How Mortadella Became An Italian Cultural Phenomenon

It is easy to mistake mortadella for bologna, though you wouldn't want to in Italy. It is said that some Italian mortadella makers view American bologna "the way French champagne producers view Ripple — with disgusted pity," per the Tenement Museum. Despite sharing its name with the famous Italian city, the bologna we're all familiar with is a far cry from the traditional, much-loved mortadella of Emilia-Romagna. While the two may have a shared, albeit strained, heritage, mortadella is far more refined and specified than the cold cut you peel out of a plastic bag.

Mortadella, according to MasterClass, is made of "heat-cured pork and fat cubes." The fat cubes come from the throat of the pig and create the signature mottled appearance of a mortadella slice. This fat remains unmelted and tender during the baking process, which is how it retains its cubed shape. Like other meats and foods in Italy, mortadella is a PGI — Protected Geographical Indication — with a very specific set of rules on how it is made, where it comes from, and what exactly can be called mortadella.

From ancient Rome to Sophia Loren: 2,000 years of popularity

Mortadella, according to Vice, has been a staple of Italian culture since ancient times, historically used as part of the rations that fed the Roman army. By the Middle Ages, over a quarter of Bologna's entire population was involved in the manufacture of mortadella. The predecessor of mortadella's PGI was the L'Arte dei Salaroli, a guild founded in 1242 to protect the integrity and quality of this cherished meat. By 1661, a papal decree created a legal definition of mortadella, solidifying the work of the guild. Creating "fake" mortadella was not a crime that was taken lightly. A shop owned by third-generation mortadella maker Davide Simoni is home to a 1720 decree that details the punishment: "your body will be stretched on the rack three times, you will be fined 200 gold coins, and all the food you make will be destroyed."

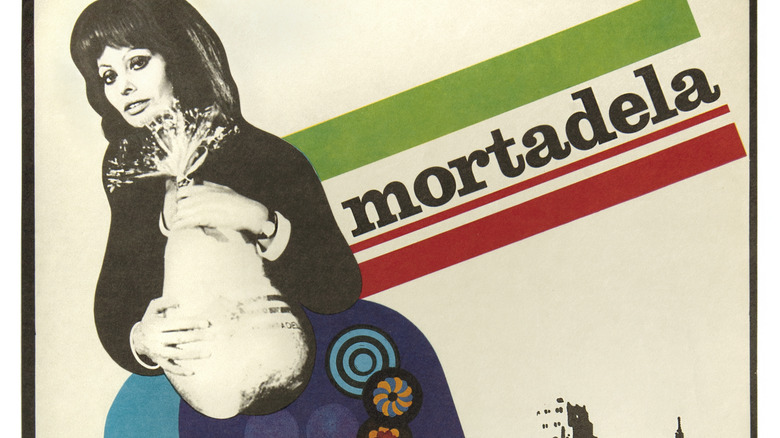

While there is no longer mortadella-related torture happening on the streets of Bologna, the meat is still very seriously beloved. Mortadella is very versatile, it can be ground up and used in meatballs, stuffed into ravioli or tortellini, blitzed into a mousse and served on crackers, or sandwiched between foccacia for a satisfying lunch (via MasterClass). Mortadella is so beloved, Sophia Loren tried to smuggle some past U.S. customs in the 1971 film "La Mortadella," ("Lady Liberty" in the U.S.). How much more iconically Italian can you get than that?