The American President Credited For Bringing French Fries To The US

Venture into an American restaurant or pub these days, and you're likely to encounter classic offerings like burgers, hearty sandwiches, and pulled pork or BBQ. While the pillars that support the concept of "American cuisine" are as arbitrary as they are ubiquitous due to the nature of the United States' cultural melting pot, to dig a little deeper into popular foods considered quintessentially "American," we are perhaps best guided by statistics. According to PBS News Hour, Americans eat as many as 50 billion hamburgers each year, at an average of three patties per week. But what would these indispensable favorites be without their best-loved side dish, the omnipresent, alcohol-absorbent french fry that we eat 4.5 billion pounds of per year via Grit)? And how did it become such a staple in the United States?

It may surprise you to learn that the answer reaches back almost as far as the birth of the country itself, to a time when American leadership was looking for European allies who shared a mutual disdain for Great Britain (via the U.S. State Department). France was an obvious candidate, although it had its own revolution brewing under the reign of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. During this time, the king was fed excessively opulent meals, featuring extravagant dishes using the most sought-after ingredients. Culinary biographer Thomas J. Craughwell relates that this stood in stark contrast to the majority of French citizens, who rejected the crown's wasteful excess and turned instead to simple, yet refined, cooking practices that one American president would fall in love with.

Which Founding Father brought french fries to America?

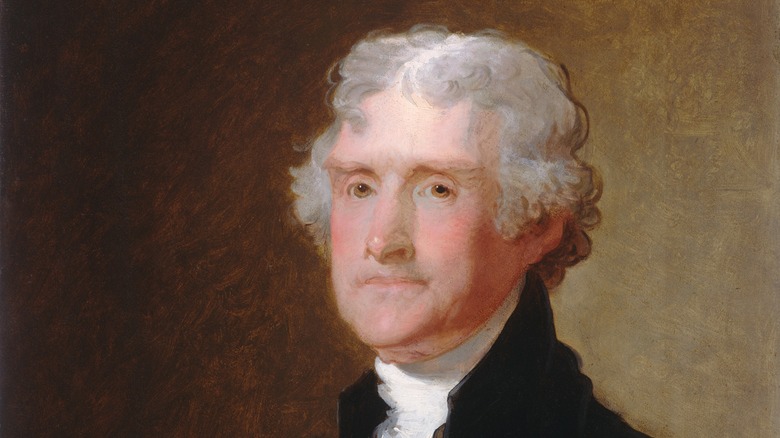

The president and Founding Father credited with bringing french fries to the new world was none other than Thomas Jefferson — quite the gourmand, food enthusiast, and experimental gardener in his home state of Virginia. At Monticello, his plantation, he purportedly planted an extensive garden with over 300 kinds of vegetables, notes The Jefferson Monticello, along with orchards of apple, peach, apricot, and almond trees, and experimented with testing various imported plants' suitability to the Virginian climate.

Traveling as a minister to France in late 1784 with his enslaved worker (and later chef), James Hemings, Jefferson later found himself sympathetic to the cause of the French Revolution. In fact, he once commented that "this ball of liberty ... will roll round the world" (via Library of Congress) in reference to the American Revolution less than 10 years before and its worldwide ripple effects. However, the influence between the two countries was not one-sided: It was during his travels that Jefferson was introduced to the simple delights of French cuisine — and adored it so much he arranged for Hemings to train in traditional French cooking while in Paris (via The Jefferson Monticello).

When Thomas Jefferson had his first french fry, though, it was called "pommes de terre frites à cru, en petites tranches," literally translating to "raw, fried potatoes, thinly sliced," according to Craughwell's culinary biography "Thomas Jefferson's Crème Brûlée." In fact, the OED details that it seemingly wasn't until the mid-1800s that they were first referred to as "french fried potatoes" in print, with the term "french fries" arriving the following century.

Jefferson's and Hemings' culinary impact on America

While there are those of you who may be thinking about Belgium's claims to be the source of the french fry as far back as 1680, France inarguably did a great job assimilating deep-fried, potato-y goodness into its own cooking with dishes like steak frites – and it was from France with love that Jefferson and Hemings brought it to America.

There were many other European foods Jefferson adored and introduced to the United States, reveals Craughwell, like crème brûlée and the ever-popular mac and cheese. Whatever "American cuisine" means to you, some of our most popular foods have been brought to us by the merit of other cultures. So perhaps the most "American" quality of the "french fried potato" is its culturally-adaptive nature.

Taken from the original, straight-edge Belgian style to the "small cuttings" popular in 1700s France, the french fry as we know it continues to evolve and meld with other cultural influences — from the dense, comforting, and traditional poutine to chili cheese fries, trendy truffle fries, and more. As it turns out, Americans have been devouring french fries in various forms for hundreds of years; the ones served at Jefferson's Virginia home, as relayed by a relative, were likely cut "in shavings round and round, as you would peel a lemon" (via National Geographic). So whichever way you take your fries, the next time National French Fry Day rolls around in July, be sure to think of the president responsible for introducing his love of French gastronomy to the U.S. — and James Hemings, the man who did his cooking!