12 Foods That Resulted Out Of Wartime

As Napoleon (or was it Frederick the Great?) said, "an army marches on its stomach" (via Oxford Reference). That doesn't mean soldiers slither around everywhere like snakes. Instead, the saying attests to how little you can accomplish with an army that isn't well-fed.

Food and war have always been intrinsically linked. If you're moving enormous groups of people through foreign territory, you'd better have a good plan about how to feed them. The problem of how to keep troops fed has inspired many culinary breakthroughs over the years. You'd be surprised by how many common dishes started out as soldiers' rations.

That's not the only way war leads to developments in food culture, either. As much as war affects soldiers, it perhaps impacts civilian populations even more. It's a sad fact that conflict often leads to food shortages, whether because of rationing or simply because fighting disrupts food production. However, people's will to survive is strong, and the ingenuity of hungry civilians has led to the creation of many wartime dishes that later went on to find widespread acceptance Read on to discover some popular foods that either were invented or popularized during wartime.

Budae Jjigae

The origin of this spicy, meaty dish is obvious from its name — at least if you know Korean. Budae jjigae translates to "army stew," and it's often called "army base stew" in English. It was created during a difficult time in South Korean history after the end of the Korean War in 1953. The war took a toll on the country, and in the aftermath, food shortages were widespread. It was very difficult to find meat to cook with. One of the only sources of animal protein was U.S. military supplies smuggled from army bases. These mostly consisted of preserved meats like Spam and hot dogs (via BBC Travel).

Although the history of the dish isn't entirely clear, one widely-accepted origin story is that it was first cooked up by Heo Gi-Suk, a woman who ran a fish cake stall close to a U.S. army base. She made stir-fries with leftover meat sourced from the base, but one day a customer gave her the idea to turn the meats into a stew instead. Thus, budae jjigae was born.

There are as many variations of budae jjigae as there are cooks preparing it. It marries Korean ingredients like anchovy broth, kimchi, chili peppers, and ramen noodles with American imports like Spam, hot dogs, and even sometimes canned baked beans and American cheese. Although it started as a dish born of necessity, it is now a beloved part of Korean food culture.

Wacky cake

What's so wacky about wacky cake? It doesn't have strange secret ingredients — quite the opposite, in fact. The thing that makes wacky cake strange is what it lacks: eggs, milk, and butter (via Contingent Magazine).

Wacky cakes originated as war cakes. They were born during the tough times and scarcity of the World War I era when food rationing made certain ingredients difficult to come by. Instead of butter, they use oil, and plain water subs in for milk. Although World War I ended, the recipes for these cakes never went away, and they became popular whenever economics or war made homemakers have to try to put dessert on the table with limited resources. The war cakes were rebranded as Depression cakes and then finally became wacky cakes during World War II.

Although most American households have no problem sourcing milk, butter, and eggs these days, wacky cakes are still worth making. They're quite easy to put together (no laborious creaming of butter and sugar is required), and they just happen to be plant-based as well.

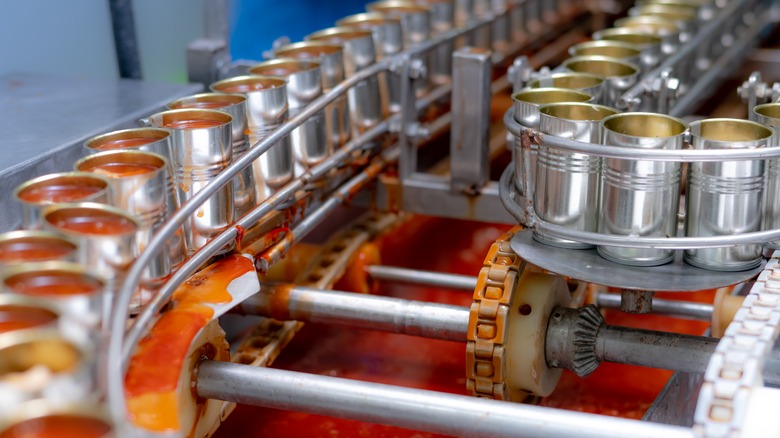

Canned food

Canned food is shelf-stable, easy to transport, and doesn't need to be cooked — all good attributes for military rations. It's no wonder then that the modern canning process was invented as a way to feed soldiers. In 1795, France was mired in conflicts across multiple continents, and the government decided it wanted to spur innovation in food preservation technology by awarding a 12,000-franc prize to encourage inventors to figure out how to keep food fresh (via History).

It took a while, but in 1809 a man named Nicolas Appert finally developed a technology worthy of claiming the prize. He figured out that sealing food inside an airtight jar and cooking it for long enough at a high enough temperature would make the food inside the jar shelf-stable for as long as the jar remained sealed. Per Britannica, a British inventor, Peter Durand, began using Appert's method to preserve food inside of iron cans just a year later. His canned goods supplied the British Navy in the 1800s.

Intriguingly, can openers weren't invented until decades after canned food became a common part of military rations. Can openers saw their first widespread use during the American Civil War, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Condensed milk

It turns out the roots of pantry staple sweetened condensed milk can be traced back to the Civil War. According to Mcgill University, Gail Borden began experimenting with condensed milk in 1853. Borden was inspired to create a canned, shelf-stable milk product by seeing people contract food-borne illnesses from drinking expired milk (via Lancaster Farming). In the days before refrigeration, condensing milk and canning it was a good way to preserve it. Borden founded his famous Eagle Brand condensed milk company in 1856.

Although Borden's condensed milk solved a real problem, his first forays into business were unsuccessful. Per Mcgill University, his first two factories went out of business, and condensed milk didn't catch on until the American government began ordering it in bulk to feed soldiers during the Civil War. Sweetened condensed milk continued to be popular after the war ended, and the company that later became Nestle was founded as a European condensed milk manufacturer inspired by Eagle Brand's success.

Croissants

Croissants may seem quintessentially French to the average American, but this baked good is actually a relatively recent addition to the canon of French patisserie. According to Smithsonian Magazine, croissants came to France from Vienna and were regarded as a foreign treat in Paris until sometime in the 1800s.

The croissant as we know it today — a pillowy mound of buttery puff pastry — is undoubtedly a French innovation. The French were the ones who figured out how to make puff pastry (and we can all be thankful to them for that). However, the French croissant is a descendant of the Viennese kipfel, which lent the croissant its distinctive crescent shape.

Like many traditional foods, the origin of the kipfel is shrouded in myth and mystery. However, the most popular origin story for this moon-shaped treat is that it was first baked to commemorate the defeat of Ottoman invaders by Austrian forces in 1683. According to the legend, a baker played an important role in ending the Ottoman siege of Vienna. The kipfel memorializes Austria's victory in two ways: It's a baked treat, and its crescent shape is a reference to the design on the Ottoman Empire's flag. In actuality, they existed before this famous military victory, but the story is so widespread in Austria that kipfels are indelibly linked to their supposed wartime roots.

Woolton pie

The original name of this dish, Lord Woolton pie, makes it seem like a fancy gourmet recipe. That impression is strengthened by the fact that the recipe was developed at London's posh (and very expensive) Savoy Hotel by Maitre Chef de Cuisine Francis Latry. However, all is not what it seems with this savory pie.

Lord Woolton (whose given name was Frederick Marquis), served as Britain's minister of food during World War II. Rather than being a luxurious delicacy, Woolton pie was a pragmatic way to get dinner on the table during a time when food in Britain was heavily rationed (via Bromley Historical Times). As a newspaper article from 1941 proclaims, this pie is nutritious and economical. Some people might even have thought it was tasty, though per History Extra, it wasn't exactly beloved.

To make it, you boil chopped vegetables with spring onions and stock extract, thickening the liquid with oatmeal. The 1941 recipe republished by the Bromley Historical Times notes that you can top it with either a whole wheat crust or potatoes. We can imagine that this would be wholesome and filling during hard times, and it would even be vegan if you used vegetable oil to make the crust.

Fry bread

Although in the present day, many people think of fry bread as a traditional Native American food, its history has as much to do with colonization and violence as it does with Indigenous traditions. According to The New York Times, the invention of fry bread is usually credited to the Diné (who you may also know as the Navajo).

Per the Partnership With Native Americans, Navajo people began making fry bread during a time known as the "Long Walk" when they were forcibly evicted from their homeland in Arizona and had to march hundreds of miles to a reservation in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. Far away from their traditional sources of food, the Navajo had to rely on basic commodities supplied by the U.S. government like white flour, fat, and sugar. Thus, the fry bread we know today, a leavened white dough deep-fried in oil and eaten with a variety of sweet or savory toppings, was born.

Although the displacement of the Navajo might not be viewed as a war by some, the U.S. government used weapons of war to eradicate native people from Arizona. Soldiers burned people's homes and deprived the Navajo of access to food and water (via the Smithsonian Institution). For that reason, fry bread holds a complicated place in Indigenous food culture. It can be seen as both a symbol of what was taken from Native Americans and a marker of perseverance during even the toughest times.

Chili

There are a great many origin stories for chili con carne, but it is generally agreed that the dish was popularized in San Antonio, Texas, by so-called "Chili Queens" who ran outdoor food stalls in the 1800s. San Antonio has been a military town for much of its history and many famous battles have occurred there, so regardless of when exactly you believe chili got its start in the city, there's a good chance soldiers were involved somehow.

According to Texas Monthly, one of the chili origin stories with the most compelling documentation comes from 1813. It also serves as the starting point for Tex-Mex cuisine. In the early 1800s, San Antonio (and Texas as a whole) was still ruled by the Spanish monarchy. A group of rebels that included Spanish Mexicans, French Creole people from Louisiana, and people of English descent wanted to change that, so they raised an army and conquered San Antonio. After taking the city, the rebels executed their royalist prisoners after lying and saying they would keep them safe.

The violence understandably angered San Antonio's residents, who refused to feed the invaders. However, one woman from a royalist family fell in love with a rebel soldier, and together they started a restaurant where she cooked Mexican food for the rebels. That woman, Jesusita de la Torre, is credited as the first San Antonio Chili Queen.

Spam

Per Time, Hormel started making Spam in 1937. That was just in time for the product to become an important part of the U.S. military's rations during World War II. It became especially prominent in the Pacific theater, and Spam entered the diets of people living in places like Guam, the Philippines, and Japan where U.S. troops were stationed. In many regions in the Pacific, the war had totally destroyed domestic food production, so rations of Spam from the U.S. became an important survival tool right after the war. Sometimes the U.S. basically forced people to eat Spam, as was the case with Japanese-Americans who were fed Spam in WWII-era internment camps.

Much like fry bread for Native Americans, Spam's history in the Asia-Pacific region is complicated because it was introduced during a time of violent hardship. It is in some ways a symbol of the reach of American colonialism. However, it is undeniable that cooks in Asia and the Pacific islands have found many delicious ways to insert Spam into their own cuisines. There is budae jjigae from Korea, as well as Hawaii's Spam musubi, Singapore's Spam curry, Spam sisig from the Philippines, and Spam macaroni soup from Hong Kong, just to name a few (via The Guardian). Spam has proven to be the ultimate shape-shifter, blending in with flavors from across the globe.

Bagels

The bagel origin story probably falls into the apocryphal category, much like the origin story for croissants. In fact, the conflict that purportedly gave us bagels is the same one that the kipfel story commemorates: the defeat of Turkish Ottoman forces by Austria in 1683 (via The Atlantic). There's also a story that cappuccinos were created as a result of that conflict, so we have a lot to thank 17th-century Austrian soldiers for (via Smithsonian Magazine).

While kipfels were supposedly a tribute to the heroics of a Viennese baker, according to The Atlantic, bagels commemorate the bravery of Jan Sobieski, who was the king of Poland and Austria in 1683 and led the troops that defeated the Ottoman invaders. Sobieski was a famous equestrian, and the round shape of a bagel is, at least per this story, supposed to look like a stirrup. At least this tale is supported by etymology. The German word for stirrup is beugel.

Whatever the true origin of bagels is, this round, chewy bread spread across Eastern and Central Europe, gaining popularity in Poland and Russia. The famous New York-style bagel that we Americans know and love is the product of Jewish immigrants from these regions who arrived in the U.S. in the early 20th century.

M&M's

The origin legend of M&M's traces back to the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. Per MoMA, candy magnate Forrest Mars, Sr. went to Spain during the war, and that's where he first saw people eating chocolate pellets covered in a candy shell. The candies were good for soldiers because the sugar coating prevented them from melting.

However, it must be mentioned that Mars was living in England at the time he made his purported Spanish Civil War discovery. England already had a very popular candy-coated chocolate confection: Rowntree's Chocolate Beans, which had been produced since 1882 and were renamed Smarties in 1937 (via the BBC). Smarties and M&M's are basically the same kind of candy, so it seems very possible that Mars' "invention" was just a Smarties ripoff.

Even if M&M's didn't actually come from the Spanish Civil War, they played a big role in wartime anyway. When they were first produced in 1941, they were exclusively sold to the U.S. government as part of soldiers' rations. Mars started selling M&M's to the general public only after the war had ended, according to History.

Energy bars

In Anastacia Marx de Salcedo's book "Combat-Ready Kitchen," she makes the case that modern protein and energy bars came about as the result of decades of U.S. military-funded research (via Popular Science). The predecessor of the modern protein bar was the Logan bar, also known as Field Ration D. These chocolate bars were manufactured by Hershey to be used as calorie-dense emergency rations during World War II. Of course, regular chocolate melts easily and tastes good enough that soldiers might not wait for an emergency to eat it, so Hershey created a special kind of chocolate that resisted melting and didn't taste all that good (via Hershey Community Archives).

Per Popular Science, after the Logan bar experiment, the U.S. government funded research into "intermediate moisture foods" that would have a soft, chewy texture while being shelf-stable. As a result of this research, Pillsbury received a military contract to produce Space Food Sticks, a chewy, nutritionally-dense energy bar. Throughout the '70s, versions of this product fed NASA astronauts and were sold to the public. Although the original Food Sticks were eventually discontinued, they paved the way for modern energy bars like the PowerBar (via General Mills).