José Andrés' Advice For Actually Improving Food Security In Africa

In August, the United Nations reported that more than 37 million people living in the Horn of Africa are facing acute hunger. According to aid agency Welt Hunger Hilfe, acute hunger (aka famine) is the most severe type of hunger and typically emerges due to circumstances like prolonged drought and war. Seven million children younger than five years old are "acutely malnourished" in the Horn of Africa, which spans Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya. At the time, the World Health Organization (WHO) called it "one of the worst hunger crises of the last 70 years."

WHO Incident Manager Sophie Maes says many regions in Africa are experiencing either flooding or drought, making it impossible for food to grow. In May, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported that crop production was 58%-70% lower than average across the Horn, and at least 1.5 million livestock had died as a direct result.

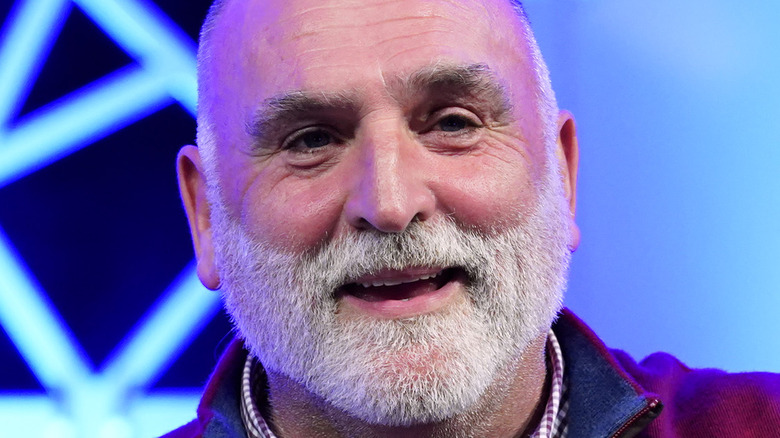

Celebrity chef José Andrés might have two double-Michelin-starred restaurants under his belt, but in 2010 he also founded World Central Kitchen, a nonprofit organization that provides food to first responders and victims of natural disasters across the globe. Most recently, notes ABC News, World Central Kitchen came to the aid of communities in Florida in the wake of Hurricane Ian, and the organization is currently providing consistent aid to Ukrainian consumers whose food access has been limited by the Russian invasion. So when José Andrés offers advice for actually improving food security in Africa, he knows of what he speaks.

Rethinking the approach to food aid

Earlier this week, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation tweeted the statistic that 80% of the food eaten by African consumers is produced domestically within Africa. José Andrés took to Twitter to respond, writing, "That['s] why it doesn't make sense that we keep sending food aid to Africa. We need to invest in systems and technology so the African people cannot just feed themselves but also to create growth and wealth [by] exporting foods."

Ned Rauch-Mannino of the Foreign Policy Research Institute agrees. Earlier this month, Rauch-Mannino listed climate change, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the declining state of the global economy as enemies to world food security, particularly in Africa. But the collateral damage of these combined factors could be just as dangerous as the immediate problem of starvation, says Rauch-Mannino. He says the large scale of Africa's food shortage could prompt "conflict and violence, democratic backsliding and human rights access, and obstacles to sustainable development."

So, what's the solution? Rauch-Mannino says increased food production, accelerated distribution, and lowered supply chain costs are crucial to combating Africa's food crisis. Patrick Youssef, the ICRC regional director for Africa, echoes the sentiment, adding that humanitarian institutions need to "address the root causes of food insecurity, not just the wounds." The ICRC has been working to set up more centers for food distribution and increase public access to seeds and farming equipment. Time will only tell what our combined global efforts must accomplish to make a difference.