Ranking 1792 Bourbons From Worst To Best

Despite what the name might suggest, 1792 bourbon is a 21st-century whiskey (the label is a reference to the year Kentucky received statehood). Nevertheless, it has been releasing bottles in the high-rye game for two decades now. The label's roots can be traced to the expert hands of the much-older whiskey legacy at Barton 1792 Distillery, which has operated since 1879. All of which is to say, this American whiskey brand has rye expertise that was a century old before rye even made its back '00s comeback.

Tasting Table attended a recent 1792 tasting in midtown Manhattan to sample its current suite of bourbons. If you're someone who avoids rye because it has so much peppery kick, stick around. You might find yourself delightedly surprised on both counts. If you're someone who seeks it out for precisely those qualities, don't leave just yet either. While this is most definitely a ranking for the common consensus on taste, it comes with some nuanced recommendations. Reality is always more complex than a simple list, and so is this suite of generally high-rye whiskeys, meaning some of you freaky and flashy drinkers looking to expand your bourbon collection may actually prefer a certain style above all the rest.

6. Small Batch

The terms small batch and high rye aren't specific legal criteria, so let's dig into their bearing on the entire ranking. Bourbon Veach notes there's no standard, but the two most workable definitions both mark the non-corn portion of the mash bill as half rye or more. While 1792 has put out a now-discontinued annual High Rye release, Distiller is confident in saying most if not all of the lineup is made from what 1792 itself calls its signature high-rye recipe or at least a few recipes that are all high-rye. Surely it's reasonable to expect a second mash bill if one expression is specifically sold under the name High Rye — reasonable, but unconfirmed.

Finding a mash bill for 1792 is a challenge — not least of all because the brand itself named a cocktail that in a savvy SEO move. By all but one of Bourbon Veach's proposed criteria, 1792 Small Batch is high rye, if Modern Thirst's assertion of 18% rye is to be believed. So 1792 Small Batch is indeed a high-rye bourbon. It drinks rather bitterly, neither as sweet nor acidic as the rest of the line. Its aroma is fruity and herbal: apple, grapefruit, clover, and ... marshmallow? Hunh.

On the tongue, you'll get a nutty oak first, then briefly brown sugar dissolving into chicory coffee. This whiskey tastes like New Orleans; nobody tell its parent company Sazerac. In summary: it's good, but for this list, it's mainly the base for what follows.

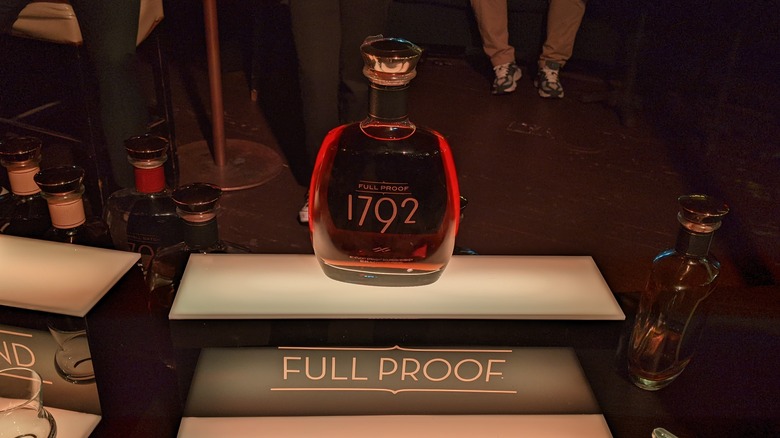

5. Full Proof

Full proof might be a new term to many, and it's all too easy to conflate it with the similar term "barrel-strength," when the final product is the same alcohol by volume as the distillate that went in there to age. The only real difference, Whiskey & Whitetails notes, is full proof is distilled back to the original entry ABV it had going into the barrel for aging. So in that regard, a full-proof bourbon is like the basically good student whose professor nudges their B+ into A territory so they can graduate from Whiskey University summa cum laude. You'll most frequently encounter the term with 1792, Weller, and — say, is this just a Sazerac labels thing?

Anyway, It would be a little misleading to call 1792 Full Proof a smooth bourbon, or at least smooth enough to remark upon, but for the fact that it is hi-test at 125 proof. In that regard, 1792 Full Proof is very smooth for what it is. Just don't walk into this one starry-eyed and dreaming of launching your whiskey-tasting career. It'll get ya if you don't know your way around, packing a kick at every step from sniff to swallow, though its aroma is just lovely, utterly lovely, with fruitiness giving way to a taste profile of cheese and cracker with a bit of grape. It's like 1792 blended up the whole cheese plate and poured it into this one bottle. If you're hardy, this is a rewarding purchase.

4. Single Barrel

If we're scoring on a scale of one to 10, our first three entrants might really come in around the same level. But out of a hundred, 1792 Single Barrel definitely edges out the previous two bottlings. Its quality is just a little bit better, but more importantly, what it embodies is more fun, albeit stock and standard to bourbons. The aroma is cherry, cranberry, and brown sugar, which is two out of three for every whiskey ever made in America.

Continuing with that tour of the classics, it's so tempting to say 1792 Single Barrel has notes of chocolate, but it's maybe more like carob, mostly brought forward on an astringency that's ...well, it's not witch hazel, but you fill in what an appetizing version of that sensation might be. Then it becomes prevalently oaky, which may even be the cause of that same aspirin-like taste. It has enough body to hold onto the middle spot, but it's a very traditional profile that leans just a bit hard into the rye characteristics that tend to divide people.

3. Sweet Wheat

It's funny, but despite the name, this wheated mash bill is only a sweet bourbon at the first fruity hit. It rapidly becomes herbal and grassy, then gives way to a darker taste that's not quite smoky but more scorch and earthy. Perhaps it's showing the char of its oak-forward personality, which is the one extant note at every stage of tasting this charming bourbon. Anti-oakers shouldn't worry too much, though, as it's more prevalent than overwhelming, and is in fact a testament to what really sets this fellow apart from its wheat-forward counterparts: It's very centrally positioned in what bourbons taste like. More than you'll find in a Weller or a Maker's Mark, Sweet Wheat will appeal to classicists who don't think a bourbon should dip its toes too far beyond the taste of corn.

Outside of the taste, it has sticky, perfectly uniform legs that speak well of its, indeed, wheat-colored presence. As is becoming a theme with 1792, the nose is really exceptional, varying between buttery baked rolls and minty, citrusy sharpness. While it's a steal when it's initially listed as a bourbon under $40, you're more realistically going to find this bottle in the wild for a very pricey $150 and up. Still, a few retailers have it around $70 to $80, which isn't out of the question for a quality sipper like this one.

2. Aged Twelve Years

It's no surprise to find lengthily aged bourbon so high up the ladder. While more age does not always equal better whiskey — particularly in bourbon and rye, which require new oaked barrels and can quickly run up against over-oaking — the folks at 1792 obviously know what they hold in hand and have priced it accordingly. The average price for Aged Twelve Years, per wine-searcher, is around $200, though it may be cheaper at your local liquor store if you're able to score a bottle for retail.

So what do you get for $200? Well, something mighty fine. Tasted without any knowledge of the price point, this definitely shot to the top of the list. But here's the catch: this is most definitely not a bourbon for everyone. This far into the aging, it's got some funky strut that will put a few folks off, while drawing in others who definitely want a tour that steps off the path. It's not for everyone, but it's exquisitely rewarding to those who do. This is really one to try at the bar before purchasing a bottle. If it's your thing, it pays dividends. If not, you'll be happier with the more familiar offerings above.

Right from the piquant, floral nose, this one will challenge you. Then it dips into a briny, nutty flavor. Pair it with a charcuterie board featuring bleu cheese and long-cured salami, or sip it alongside a dry-aged steak. When you order the Aged Twelve Years, tonight is no longer a night for mild flavors or restraint.

1. Bottled in Bond

Bottled-in-bond whiskeys have lately gotten the reputation they deserve, even among bourbon dilettantes, as a reliable way to try a new label under certain guarantees. Still, we'll be the first to say it: It's not always the better bet. If you're ever faced with the choice of Evan Williams green label or the bonded variety, pick the lower proof for flavor and leave the potent white label on the shelf. (Feel free to start slinging your outcries and outrage now, it's fine.)

The point is that the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 safeguards production and distribution, but the final results aren't guaranteed the best. Much of the Act's value is knowing where your whiskey comes from. With that in mind, four years' aging and a hundred-proof bottling will lean to a sweet spot in whiskey production.

All that said: Here's why that reputation remains largely deserved. If quality in a bonded whiskey isn't the rule, it's still a trustworthy tendency. The 1792 Bottled in Bond is the best of the lot on both the nose and the tongue. Inhaling its perfume, you're greeted by a rich and ruby perfume. Let it hit your tongue, and you'll think of salted butter — made odder by the fact that this taste is separate from the texture, which isn't creamy at all. It's the breakout bottle, even priced at about a Benjamin. If it's cheaper where you live, seize it.