27 Types Of Ramen, Explained

Those of us who grew up with packets of instant ramen in the pantry are probably pretty amazed by the breadth of ramen's many forms. The origin of ramen in Japan is relatively complex, stemming from a style of noodles imported by Chinese transplants and popularized due to a flux of U.S. wheat brought in for post-WWII food shortages. Inventor Momofuku Ando solidified ramen's fame by developing instant ramen in 1958, ensuring hungry college students and busy executives alike had access to an easy-to-make meal.

Today, these slurpy noodles are swimming in a range of broths that are turned into several different styles. Ramen restaurants spend days simmering bones with dried mushrooms and aromatic vegetables to create the perfect soup. The effort has certainly contributed to ramen's rise in popularity, but it has created some confusion. What do all these ramen terms mean, and how do you use them to pick the perfect bowl? We're here to demystify the different types of ramen you'll want to know.

Kotteri or paitan broth

It's unlikely that you'll see the word kotteri at a ramen restaurant in the U.S., but this opaque broth is one of two foundational broths used to make all soup-based ramen. The menu will likely describe this style of rich and dense broth as paitan (referring to the broth's cloudy, white color) or tonkatsu (a specific kotteri broth made with pork bones). Kotteri has several translations from Japanese, but the words "heavy," "thick," or "dense" are commonly used to describe the ramen broth. Kotteri is made by boiling bones at high heats, which makes the broth opaque in color and gives it a rich, fatty consistency.

Assari or chintan broth

Assari is the second type of ramen soup base. Yamato Noodle Japan describes this broth as "light" or "unsaturated" and notes that it's significantly less dense than kotteri ramen. You may hear assari referred to as chintan, which describes its clear character. This soup is also made with pork or chicken bones but lacks kotteri's white color because it's simmered more slowly over low heat to prevent cloudiness. This process also extracts less fat from the bones, so assari tends to be less filling as well. On a restaurant menu, you may see assari broths served as soy-based shoyu ramen or shio ramen, which refers to added salt seasoning.

Tonyu ramen

Most ramen broths are made with pork or chicken bones, but it's not uncommon to find vegetarian ramens made with charred vegetables or mushroom broth. Tonyu broth is special because it's made with soy milk, a staple ingredient in Asian cuisine. Zenbu Travel puts the origins of this soup at a restaurant called Mamezen in Kyoto and advises that the broth tastes best when made from fresh soybeans. The fresh milk lends a sweetness to the broth while providing a similar buttery character found in opaque, white kotteri broths.

The original recipe from Mamezen mixes soy milk with dashi (a broth made with dried bonito fish flakes and kombu seaweed), while other restaurants will make a vegan ramen recipe. If vegetarian ramen is important to you, it's best to ask before you order.

Shio ramen

Shio is one of the two most popular ways to serve a clear assari broth, and it's the way to go if you want to taste the soup itself. Shio means salt in Japanese, so shio ramen is seasoned simply with salt. One popular version of shio ramen is made with dashi or seafood broth, but that doesn't mean that shio is always a seafood soup. The base assari broth can be made with vegetables, chicken, or pork, but it's important that the broth isn't boiled for long or at hot temperatures so it remains clear.

Shoyu ramen

Shoyu is a clear ramen broth that is similar to salt-based shio, but it's bolder and more heavily seasoned thanks to the addition of soy sauce. While soy sauce originated in China, shoyu is unique because it refers to a Japanese style where soybeans are fermented with wheat that dates back to the 13th century. Shoyu is often added to clear assari broths, but it can also be added to thicker kotteri broths to create bold flavors. This seasoning brings out the salty notes while also adding a deep umami flavor.

Miso ramen

Another popular ramen seasoning is miso, a fermented soybean paste that adds sweet, salty, savory, and funky vibes to any dish. There are three types of miso: white, yellow, and red. White (or shiro) miso is commonly added to your ramen because of its deliciously nutty flavor. Some ramen is labeled as red ramen (or aka), referring to this longer-aged miso that's stronger flavored and quite a bit funkier. It's not uncommon to find miso paired with heat, creating spicy miso ramen, but it's also a popular addition to tonyu broths made from soy milk to add depth of flavor.

Tonkotsu ramen

If there's one type of ramen that's absolutely taken off in the United States, it's this one. You can find this dense kotteri ramen broth on almost every restaurant menu. Costco even briefly sold Tonkotsu ramen kits. According to Tokyo Ramen Tours, tonkotsu is said to be invented by mistake: A ramen maker in Fukuoka (a prefecture on Japan's Kyushu Island) accidentally let his pork bones boil for too long. It made the broth cloudy and fatty but full of rich, porky flavor. His customers loved it, and the rest is history!

Tori paitan ramen

Tori paitan is the chicken version of pork-forward tonkotsu that was invented in Osaka (via Kororo Media). This opaque kotteri broth style is made by boiling chicken bones until the liquid becomes rich and creamy. This white chicken broth is just as thick as its porky cousin, except with a deep poultry flavor. Because chicken bones are smaller and have less density compared to pork bones, they break down in a fraction of the time. As a result, tori paitan is less time-consuming to make while still resulting in a powerful burst of flavor.

Mentsuyu or tsuyu ramen

Mentsuyu (also called tsuyu) is more popularly used with soba noodles, but it is often added to ramen. This Japanese sauce has many uses, including as a side sauce for tempura, or glaze for meat, seafood, and vegetables. Tsuyu can also be used as a dipping sauce for chilled noodles, or — in the case of ramen — as a soup base.

Tsuyu ramen is made by combining sake, mirin, soy sauce, kombu seaweed, and dried bonito flakes. As a shortcut, the first three liquids can be added directly to dashi, which is a broth made of kombu and dried fish flakes. Homemade or store-bought mentsuyu can be diluted in water or broth, adding a lightly sweet flavor that's simultaneously umami-forward. The concentration of bonito flakes makes the ramen broth almost taste meaty.

Mayu or ninniku ramen

There are two main ways to add garlic to ramen, and they're both delicious. The first is with mayu, which refers to as black garlic oil or burnt garlic oil. It's not actually made with black garlic; here, raw garlic is cooked over low heat until it's almost burnt and turns black. The result is a lightly bitter but very complex oil that pairs perfectly with rich kotteri ramen broths.

If the pungent bite of raw garlic is your thing, look for ninniku ramen. These bowls contain a condiment called ninniku-dare, a mixture of grated raw garlic and pork fat. The garlic contributes a spicy edge to ramen soup while the pork fat mellows it out, adding a nice unctuousness that's especially welcome in clear, light assari broths.

Spicy ramen

There's no singular way to make ramen spicy, but these bowls all have one thing in common: They bring the heat! Some use a delicious sauce called yuzu kosho, a flavorful blend of fermented chili, citrus zest, garlic, and salt. It's citrusy and floral, but the spice is unmistakable. Other ramen shops use straight chili peppers or even hot sauce like sriracha, but it's more common to see spice added with chili oil.

Rayu chili oil is a popular choice, a sesame oil-based spice that contains chilies, garlic, green onions, ginger, and other spices. You may also see mala chili oil on the menu, a "numbing" oil made with Szechuan peppercorns.

Yuzu ramen

Not to be confused with the spicy yuzu kosho, yuzu ramen is light and delicate thanks to the addition of yuzu citrus juice. Yuzu is one of the main ingredients in ponzu sauce, and it's sour and tart but bright and refreshing. Imagine if someone crossed a mandarine orange with a Meyer lemon. The most common way to find yuzu flavoring is when it's added to light assari broths, like shio or shoyu ramen. The brightness complements the clear soup and brings out the salinity in the broth.

Curry ramen

Curry ramen is a fusion of Japanese curry and ramen noodles. It's more of a homemade meal than a restaurant item. That doesn't mean that you won't see it on a menu at American ramen restaurants, and you'll probably love it if you gravitate toward these two dishes individually.

In case you're wondering, there's a difference between Japanese curry and Indian curry. Japanese versions are more like a stew and aren't as heavy on spices. They tend to be sweet, thick, and hearty, and the sauce really does taste great when tossed with ramen noodles.

Wontanmen or wonton ramen

This type of ramen can be made with any broth or flavoring, but the name indicates that wontons are added to the soup. According to I Am a Food Blog's Tokyo Ramen guide, Japanese wontons are similar to Chinese versions, but their filling-to-wrapper ration is distinct. Japanese versions have less filling, and the wrapper becomes like an extra noodle in the soup. It's common to find wonton added to clear assari broths, like shio or shoyu. The filling could be made from anything, but pork and shrimp seem to be the most common.

Tamago ramen

Tamago is the Japanese word for egg, so tamago ramen comes with an egg in the bowl. Ramen eggs, called ajitsuke tamago or simply ajitama, are usually soft-boiled so the yolk is still runny. The eggs could also be hard-boiled for brief periods until the yolk obtains a jammy consistency. The main reason they're so special, though, is the marinating hack that takes eggs to the next level. After boiling and peeling the eggs, ramen chefs place the eggs in soy sauce. Sometimes, mirin, sugar, or vinegar are added for extra flavor. The result is an umami-rich, lightly sweet egg that's perfect alongside ramen's flavorful broth and springy noodles.

Chashu or kakuni ramen

These ramen bowls refer to a piece of braised pork that's added to the bowl right before it's served. Chashu is one of the most common toppings for ramen. Chashu is made by braising pork shoulder or pork belly in a flavorful combination of sake, soy sauce, and sugar. It can be rolled into a log or braised as a block.

Some ramen shops specialize in kakuni instead. Kakuni, on the other hand, means "square simmered," referring to how the pork is cut into a square before it's braised. It's always made with pork belly, giving it a fatty consistency that melts in your mouth as you enjoy it.

Yasai ramen

Vegetarian ramen-goers love yasai ramen, which is topped with stir-fried vegetables. The type of vegetables added depends on the chef, and we've seen yasai bowls that included mushrooms, eggplant, carrots, bok choy, peppers, onions, bean sprouts, and more. Most ramen menus we've seen feature yasai ramen bowls with vegetarian broths flavored with nutty miso or umami-forward mentsuyu sauce (which can be flavored with dried fish or replaced with mushrooms).

That doesn't mean you can't add yasai vegetables to meaty kotteri broths if you see both on the menu at your favorite restaurant — but that depends on whether the chef allows substitutions.

Tsukemen

Tsukemen is a specialized type of ramen, and it's not offered at all ramen joints (although, it is found at some of the best ramen restaurants in America). Instead of serving the noodles in the broth, the two are separated and the noodles are cold. The broth here is condensed and concentrated to make it extra flavorful.

To eat these dipping noodles, pick up the desired amount of noodles, dunk them into the broth to heat them up, and slurp away. Depending on the restaurant, you may also receive a side plate with braised chashu pork, a marinated ajitsuke tamago (ramen egg), or those swirly white and pink fish cakes.

Abura soba

This dish is quite distinct because it doesn't contain any liquid, a component that seems integral to a good bowl of ramen. According to Myojo, abura means oily noodles, and it's one of several popular versions of soupless noodles. Soy sauce-based flavoring and oil (usually vegetable oil) are poured into the bottom of the bowl. The noodles and toppings are layered on top, and you can add optional spicy rayu oil or vinegar before mixing the components together.

Mazemen or mazesoba

Myojo goes on to say that abura soba evolved to create a bolder, more robust version that combined Japanese ramen with Taiwanese flavors: Mazemen, another brothless ramen dish. It means "mixed noodles," referring to how the noodles are combined with the oil and flavorings before being served. Most mazemen bowls contain thick, chewy noodles, which are flavored with lard or back fat and a tare sauce similar to the flavorings you'd find added to ramen broth. It's common to find an egg yolk on mazemen bowls, and they usually come with spicy ground pork instead of chashu or kakuni.

Hiyashi chuka

It might be too hot to eat soup in the summer, and this cold ramen is the answer. It's sometimes served in a chilled dashi broth, but the noodles can also be served like a salad dressed in a sesame or soy dressing. Hiyashi chuka can be topped with anything, but you'll often find it garnished with summer vegetables. Tomatoes, corn, zucchini, summer squash, or cucumbers are common additions. It can be made vegetarian or served with meaty toppings like shrimp, imitation (or real) crab meat, sliced egg omelet, ham strips, or shredded chicken.

Tantanmen or tantan ramen

If you love spicy Szechuan noodles, you should absolutely try tantanmen, also called tantan ramen. This Japanese version turns the Chinese restaurant favorite dan dan mein into a brothy bowl, swapping out the original's thick sesame paste sauce for a broth infused with similar seasonings.

Some tantanmen bowls start with broth that's flavored with mentsuyu, but we've seen several recipes that use soy milk, oat milk, or almond milk to create a creamy consistency. A flavorful (and often spicy) ground pork mixture is an iconic topping for tantanmen bowls, and the dish won't have the same dan dan character without it.

Tokyo ramen

There are several different regional ramen specialties, and they've become so popular that you may see them on restaurant menus across the world. Tokyo is a major center for ramen restaurants, so it's no surprise there's a Tokyo-style ramen. If you see this on a menu, you can expect curly, wide noodles served in pork or chicken broth that's seasoned with shoyu (Japanese soy sauce). Dashi broth is often added to the mix, giving the soup a smoked fish and seaweed character. Tokyo ramen is often compared to Yokohama ramen, which is similar, but it has a heavier broth, less dashi influence, and more meat.

Sapporo ramen

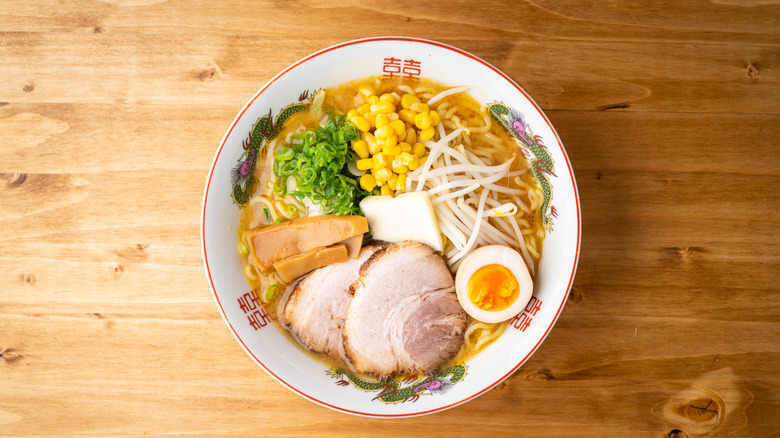

Sapporo is located in Hokkaido, the northernmost prefecture in Japan, and it's said to be the birthplace of miso ramen. This regional specialty features thick noodles specifically designed for miso. The broth is made from pork, chicken, or fish and is seasoned with red miso paste to give it a full-forward, umami character. It's bold and rich, and it's typically garnished with a pile of sweet corn. You'll know it's true Sapporo ramen if it contains a slice of butter, making the soup extra rich.

Hakata ramen

Tonkotsu ramen was invented in Fukuoka, so it's not surprising that the prefecture's Hakata district has a regional specialty based on this pork bone broth (via Zen Pop). This ramen is all about richness, and the broth is fatty and milky white from the long, hot boiling process. Hakata ramen can include seasonings like miso, salt-based shio, or soy-based shoyu, but it's generally left plain to let the porky flavor shine through. You'll find the noodles here are thinner and straighter than typical ramen noodles. They're also served al dente, starting out a little crunchy and softening up in the broth as you eat.

Onomichi ramen

The Onomichi-style ramen originated at the Shukaen ramen shop in Hiroshima Prefecture. Although the original restaurant closed in 2019, the ramen style lives on, and the combination of ingredients used to make it gives this dish a unique flavor. The broth is seafood-forward thanks to the use of dashi and the addition of fish from the local Seto Inland Sea. Before serving, it's seasoned with shoyu and topped with a pork back fat called seabura to give it a rich finish.

Ramyeon or ramyun

Instant noodles have become big business in Korea, so much so that they've spawned their own regional category of ramen. So, what's the difference between ramen versus ramyun (also spelled ramyeon)? According to the Korea Herald, it's all about whether the ingredients are fresh, so Koreans call the bowl "ramen" when it's served in a restaurant and made with fresh noodles and ingredients.

While ramyeon can be found outside the home, it typically refers to homemade versions made with oil-fried instant noodles from the grocery store. Ramyeon can include fresh ingredients like eggs and green onions, but it's more common to see it made with instant broth packets and freeze-dried vegetables.