How Booze May Have Helped Keep The Titanic's Pastry Chef Alive

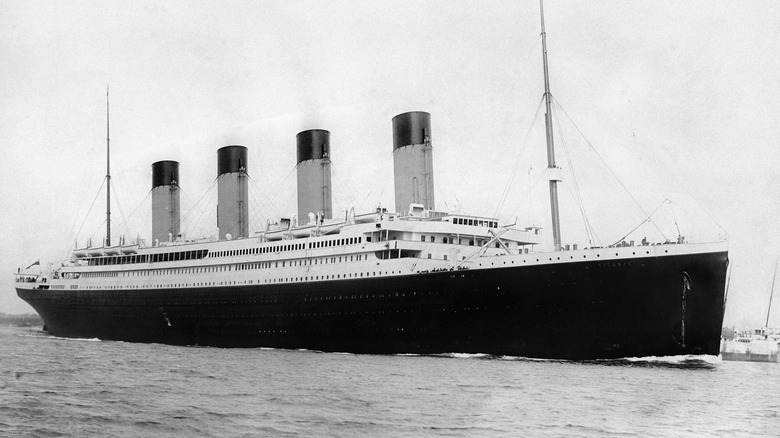

On April 10, 1912, RMS Titanic glided out from Southampton on its maiden voyage to New York. The stately palace on the waves held about 1,500 passengers of all social classes, plus more than 900 crew members (via National Post). On board was Charles Joughin, a 33-year-old Englishman and the ship's chief baker. He and his team crafted breads, cakes, puddings, jellies, and ice creams for passengers.

According to Encyclopedia Titanica, each morning after the sun had risen over the Atlantic, a bugle would blast "The Roast Beef of Old England." This signaled to the voyagers that it was breakfast time. Most first-class passengers then gathered in the white, wood-paneled dining room to eat fruit, oats, stewed prunes, fish, and meats prepared in the state-of-the-art galley kitchen (via Titanic Facts). For dinner, a chicken and banana dish was served to the Titanic's first-class diners. Also on the menu were baked items by Joughin's team, such as cornbread, Vienna rolls, graham rolls, buckwheat cakes (crepes), soda and sultana scones served with fruit conserve, Narbonne honey, and Oxford marmalade.

On April 14, passengers unknowingly sat down to their last meal on the Titanic. That evening, Joughin had devised a first-class dessert menu of Waldorf pudding, peaches in Chartreuse jelly, vanilla and chocolate eclairs, and French ice cream. He may also have concocted the palate cleanser of Punch Romaine, a dish of rum-soaked ice shards that resembled a shattered glacial mass. Just a few hours later, the ship collided with an iceberg. Against all odds, Joughin survived.

Charles Joughin sipped a dram as the ship sank

He gallantly refused a seat on a lifeboat and, in fact, seemed to be in no hurry to leave the ship. Instead, his survival strategy (if he had one), seemed to be based around keeping a cool head — and getting cock-eyed drunk. As outlined by the National Post, Charles Joughin was in his bunk when he heard the sickening crunch of the iceberg collision. He then mobilized his team. They took bread and biscuits from the kitchen to stock the lifeboats, then he returned to his cabin for a stiff drink before returning to throw people — sometimes forcibly — into boats.

It's possible that Joughin was aware that there weren't enough lifeboats for everyone on board, so he was resigned to staying on the ship. At any rate, by the time the decks had been emptied of safety vessels, he continued slinging back whiskey in his cabin, watching as water seeped into the room. He then waded up to the main deck and, when the Titanic split in half at 2:20 a.m., stood at the rail beneath the stars as it sank. Once he hit the icy water, he paddled in it for hours before the light of dawn revealed an upturned lifeboat. After swimming over to it, he waited until he was rescued by another boat.

Did 'Dutch courage' save Charles Joughin?

But how exactly did Charles Joughin survive when so many others panicked and drowned after hitting the freezing water? After all, alcohol lowers your temperature (via Patient), so surely the drinking would have put him in a worsened position?

It seems that as well as being brave and cool-headed, Joughin was also extremely lucky. According to hypothermia expert Gordon Giesbrecht (via National Post), he hit a sweet spot where the water, at a temperature of 28 degrees Fahrenheit, was cold enough to cancel out the effects of the alcohol. If anything, the liquor probably helped him, making him calmer so that he didn't panic and start flailing around when he hit the sea. He was able to wait out the first 90 seconds of shock that the body enters when landing in an icy ocean, then treaded water until he was rescued. Plus, as he was possibly among the last to leave the ship, he had to spend less time stranded at sea.

You would think that Joughin would have had enough of ships after the Titanic. But according to The U.K. National Archives, he went on to join the merchant navy, then worked as a baker on troopships during World War I. And although he didn't talk to many people about the tragedy, he went down in history as the drunken pastry chef who stood on the ship as it sank — and lived to tell the tale.