The Boston Tea Party Myth You Should Stop Believing

America might run on Dunkin', but there was a time when Earl Grey would have been a more common pick-me-up in most corners of the U.S. of A. In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, inhabitants of the original thirteen colonies came to view tea as both a daily necessity and an important social custom, as afternoon tea drinking offered a means to hospitality and camaraderie (per The Met).

The Museum of the American Revolution reports that early Americans picked up the habit around the 1720s when the English started importing tea to the colonies from China, and roughly half of colonial households owned a tea set by the middle of the eighteenth century, according to "The American Plate: A Culinary History in 100 Bites." It wasn't until around the Revolutionary War that patriots switched to coffee to distinguish themselves culturally from their British counterparts (per PBS).

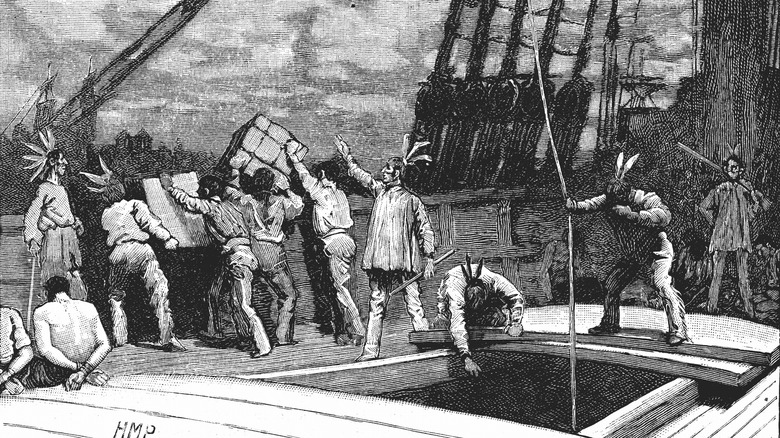

Tea drinking famously came to a head after the Boston Tea Party of 1773, when American rebels dumped 45 tons of tea from the British East India Company into the Boston Harbor, destroying about a million dollars worth (in today's value) of merchandise (per Time). But the reason behind this fiasco is often woefully misremembered.

The Tea Act made tea cheaper

You may vaguely recall something about the Tea Act of 1773 from middle school history class. You might remember that the Boston Tea Party participants trashed all that tea because the Tea Act raised taxes on tea in the New World. But this isn't true!

The Tea Act actually made tea cheaper than it was before by giving the East India Company a monopoly on importing tea to the colonies (via UShistory.org). The East India Company was a massive trading company that made money selling spices, cotton, silk, indigo, opium, and tea throughout the British Empire (per Britannica). And according to History, The Tea Act allowed the East India Company to ship tea directly to the colonies without first stopping in England. This meant that they no longer had to go through middlemen who jacked up prices for the consumer, and they no longer paid an additional tax while going through the mainland.

Here's the tea: This might sound like an overall good thing for tea drinkers in the colonies, but Time reports that it cut out wealthy colonial middlemen and smugglers (John Hancock among them) who feared for their profits now that the Brits could ship tea directly to consumers. So it was less about "no taxation without representation" and more about individuals looking out for their own self-interest.