What US School Lunches Looked Like Through The Decades

Though cafeterias, trays, and lunch lines are now ingrained in the memories of anyone who attended school, school lunches are a relatively recent invention. In fact, the school lunch experience is only about a century old. It's undergone significant changes since its inception, including purposed-based cafeterias for eating, kitchen staff, and menus that offer a variety of choices to young students.

The evolution of what lands on the plate has changed significantly too, as have all food trends in the last 100 years. What began as community stews and soups evolved into meatloaves and plates of chipped beef as the U.S. moved through the Great Depression and WWII rationing. Then, the rise in burgers and tacos on the school lunch menu eventually gave way to fast food companies like McDonald's taking over cafeteria offerings altogether in response to steep federal budget cuts to school lunch programs in the 1980s.

In the last 20 years, in the face of growing health concerns like childhood obesity, school menus have been revamped in hopes of returning to their original purpose of providing healthy, nourishing options to the next generation. If you've ever wondered how tater tots, square pizza, or other items became such a mainstay of school cafeteria foods or wondered why school lunches in the U.S. are so different than what's offered in other parts of the world, read on to see what school lunches looked like over the past 100 years.

Free or subsidized school lunch programs began as individual city initiatives

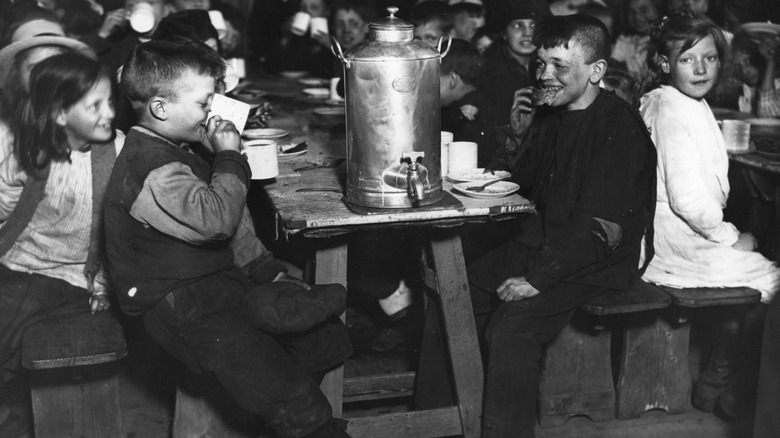

Before the early 1900s, most children lived close to school and went home for lunch. During this period, lunch was considered the main meal of the day rather than something to be rushed through or skipped altogether. Those who lived in more spread out or rural areas would bring a cold packed lunch to eat or ingredients to be put towards a communal stew using the school's kettle, which would be eaten on-site by all who contributed. During this time, school cafeterias didn't exist, so lunch for those who remained at school would be eaten at each student's desk.

However, as industry and commerce grew, mothers increasingly worked outside the home, parents began taking jobs further away from the house, and more children were forced to remain at school during lunchtime. This resulted in an increasing demand for a school-based lunch program to meet the needs of communities nationwide.

Boston and Philadelphia first implemented such programs

Fueled and funded by organizations like the Women's Education and Industrial Union, beginning in 1894, Philadelphia began serving students hot meals known as "penny lunches," including hot soup and crackers.

In 1910, thanks to the home economics department, students needing lunch at Boston's Trade School for Girls would be provided with more elaborate offerings. Lunches included items like celery soup with croutons, stuffed tomatoes, apple shortcakes, and baked beans with brown bread. Meals were prepared by girls enrolled in the school's home economics or domestic science program, proving to be a valuable system for both sides of the experience. The Boston-based program's success grew, eventually supplying and supporting eight local schools from the one kitchen, which distributors would then deliver.

These home economics classes became the driving workforce behind the city's school lunch program, providing hot meals to elementary schools every three days a week when class was in session. On the days that classes didn't meet, sandwiches and milk were on offer instead.

Local volunteer organizations ran school lunch programs for many years

School lunch offerings ranged based on the backing and popularity of volunteer-led organizations, whether it was the Women's Education and Industrial Union or the New York School Lunch Committee. This meant any program was subject to whatever local volunteer-based resources were available rather than federal or even state-level support.

In Pinellas County in Florida, the school lunch program relied on ingredient donations from parents to create a communal stew for students. In New York, the lunchtime meal often consisted of pea soup, lentils or rice, and a slice of bread. Desserts and sides cost extra, like rice pudding, stewed fruits, or candied apples. In rural Wisconsin, students would bring in pint jars filled with foods like pasta, soup, or cocoa, which teachers would place in buckets of water above the stoves that heated the classrooms.

Despite more than 40 cities across the nation working to establish a lunch program to help meet the growing need for such support, without national support and structure, these programs were at the mercy of each area's resources. They lacked consistency and substantial nutrition at times. Moreover, the responsibility to provide nourishing hot meals increasingly fell on the shoulders of home economics teachers and students, eventually evolving into systems and setups that would shape the modern-day cafeteria.

The Great Depression played a part in transforming school lunches

The Great Depression, the steep downturn that wreaked havoc on every aspect of the American economy from 1929 to 1941, has, unsurprisingly, played a significant part in shaping the American food system. Many defining food trends, from convenience foods to the popularity of meatloaf, resulted from this time of scarce resources and funds, including the American school lunch. Nutrition requirements also became fundamental in supporting war efforts, with potential soldiers rejected from joining the military if there were indications of malnutrition, as was often likely. During this period, Recommended Daily Allowances, or RDAs, were created to guide school lunch efforts.

A government initiative was also created to help boost the country's agricultural industry and support farmers whom the effects of the Great Depression had also hit. The Department of Agriculture offered to purchase any surplus of crops or products that farmers weren't able to sell, including meat and dairy from farmers. Many of these supplies were then used as resources for school lunch programs.

While the financial relief and the reduction of wasted goods were benefits, they distinctly shaped what went onto the plates of school children, with meals being dictated by what needed to be used up rather than necessarily what was a nutritional, balanced, and sound meal. This national legislation eventually put plans into motion that would support the National School Lunch Act.

In 1946, the National School Lunch Act established a nationwide program

By the early 1940s, a nationally recognized school lunch program had already been established in each state due to growing needs. However, WWII affected the amount of funding and the available workforce to support the programs, leaving the programs vulnerable. So too was the unreliability of supplies. Though purchasing surplus goods from farmers was initially a good idea, they were often unpredictable, arriving without warning and unable to be used at the last minute or needing refrigeration beyond the school's capacity. The USDA responded by producing a meal planning guide for schools with ideas and recipes on how to turn the excess ingredients into lunch, including dishes like chipped beef, Spanish rice with bacon, and a pork-based hash brown that became known as scrapple.

In 1946, President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act. The act provided official legislation for funding and recognized the importance of feeding school children. For the first few years, lunch programs still relied heavily on subsidized produce. Simultaneously, cafeterias, first established to serve factory workers too far away from home for a midday meal, became a muse for the school-based cafeteria aiming to provide the same space and service but for school children. These restaurants often served fast, low-cost foods including burgers and spaghetti, with slices of pie or cups of Jell-O for dessert. They were perfect models for schools, allowing for efficient service for large groups of people.

Private food companies sought lucrative contracts nationwide

In raising the "Baby Boomer" generation, named appropriately after a surge in births following WWII, an increasing amount of supplies was needed to meet the heightened demand from the new generation of school children. Such demands included more protein-rich foods to compensate for lost time and calorie deficit during the years of food rationing. This increase in protein saw foods such as cheese meatloaf, ham and bean scallops, and sausage shortcakes landing on cafeteria lines and trays nationwide. Even desserts now contained proteins, including foods like yogurt or cottage cheese alongside a serving of orange and coconut custard.

It was around this time that private companies started to get involved in what were previously government-funded initiatives. Not only were demands on the rise but so were potential earnings. Branded lunchboxes, depicting popular characters from national television shows from Mickey Mouse to Gunsmoke, also began appearing in cafeterias, thanks to children who brought a packed lunch. There were many different ways to capitalize on this captive audience. School lunch, whether packed or purchased, became a mainstay in many schools across the country.

In the 1960s, pizza and other regional foods were added

Given the nationwide expansion of school lunch programs, menus were no longer just for targeted communities. Variety was needed to appeal to a wide range of ethnicities and backgrounds. Items like pizza, enchiladas, tacos, or chili became commonplace on the weekly menu. So, too, was a rise in convenience foods like fish sticks or catch-all items like peanut butter and jam sandwiches or meatloaf and mashed potatoes, which had remained on the menu since their post-Depression rise in popularity.

Once more, feeding hungry children wasn't only seen as a responsibility and duty as a nation. It also became an incentive for the growing commerce which supported the farming industry. School lunch became a lucrative industry, creating new work opportunities by staffing cafeterias and continuing to boost revenue for privately owned companies. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed what is known as the Child Nutrition Act, a further arm of funding meant to provide and maintain the quality of school lunches extended to low-income families nationwide, and subject to review every five years.

Fast food became a school lunch menu norm as nutritional requirements slipped

By the mid-'70s, school cafeterias across the country saw a steep rise in offering what could now be considered typical American fast foods. This included weekly burgers, burritos, pizza, fried chicken, tacos, and tater tots that are now ubiquitous to present-day school menus. The popularity of these foods among students only made it easier for the eventual takeover of cafeterias by actual fast-food chains that were just around the corner. It seemed American palates and minds were being trained from a young age that these foods were a regular part of daily life.

Like every other system, the National School Lunch Program, and what foods and funds are on offer, is a byproduct of American history. Funding needs, time, and workforce poverty present during the World Wars and the Great Depression greatly shaped school lunches in the U.S., distinctly differentiating them from many of the meals provided by other school lunch programs worldwide. As more and more fast food items appeared on America's lunch menus, it had an inverse effect on the nutritional value of each meal.

Nutritional guidelines under Reagan classified ketchup as a vegetable

The 1980s brought chaos to the national table, including what was considered an acceptable meal for school children. Ketchup and pickle relish became acceptable so-called vegetables when served alongside french fries or hamburgers. Hamburgers could be cut with a soy filler to stretch the meat further. These new guidelines also included reducing the quantity and quality of food requirements. An acceptable lunch serving for a six-year-old was whittled down to half a piece of bread, half a cup of fruits or "vegetables," and one ounce of meat. This would be barely enough to sustain a toddler, let alone a child three times the size.

Now seen for the ridiculous and cruel excuses that they were, the cuts and lowering of nutritional requirements were a response to a $1 billion axe taken to the school lunch program, which provided lower-income families with subsidized school meals. This was met with other excuses, including the USDA echoing similar sentiments by claiming that school lunches only needed "minimum nutritional value," providing the perfect opportunity for the tsunami of fast food operations that would soon take hold.

By the '90s, fast food franchises took over cafeterias

Just in case the ketchup-as-a-vegetable issue wasn't enough, by the mid-90s, the government waved through a new era of nutrition-less school lunches. With the ever-growing popularity of fast food throughout the country, school cafeterias became an untapped market. Corporations like McDonald's were granted permission to set up franchises inside lunch halls, creating both a financially viable lunch program for many schools that were struggling to keep theirs going and a new generation of loyal customers. It was considered a win for everyone (except for the health of the kids).

Holy Cross High School in San Antonio was the first to link up with McDonald's and franchise inside the school gates, with many others soon to follow. Concessions revamped menu items to ensure they met the minimum nutritional requirement, which had fallen to such low standards that it wasn't much of a stretch.

Vending machines were also increasingly prevalent at this time and were equally good money-makers for schools. Even packed lunches contained a range of convenience foods devoid of nutrition, from Gushers to Squeezits.

Campaigns to improve school lunches took hold in the early 2000s

By early 2000, it was evident that the health of America's youth had suffered at the hands of cafeteria-invading fast-food chains and the policymakers who let them inside. More than half of all U.S. schools have either junk food-distributing vending machines, fast food franchises, or both. Unsurprisingly, childhood obesity rates skyrocketed in a way that officials couldn't ignore.

Under the Obama administration, a new Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was signed into legislation. The act hoped to address the quality of school lunches, improve their nutritional value, and provide support to understand food insecurity issues better. It was coupled with other exercise initiatives to improve the overall health and school environment. Celebrity chefs like Jamie Oliver also become involved in campaigning for better school lunches both in the U.S. and the U.K.

During this time school lunches were slightly revamped to include more fresh fruits and vegetables, adding vegetable toppings and sides, and items like turkey hot dogs to the standard fast food offerings. Though the objective was admirable and necessary, these so-called nutritional improvements weren't always successful. Some schools simply reduced the portion sizes to meet the newly revamped national standards.

The future of school lunches remains to be seen

2020 saw unprecedented universal access to a free lunch for all students enrolled in public schools. The waving of school lunch costs helped families from a wide range of economics — a staggering change to the standard three-tier system, which had led to reports of shaming against students with outstanding debt on their accounts. Such students were reportedly subjected to public humiliation, including hot meals publicly dumped by staff in exchange for cold sandwiches for any outstanding debt.

Universal access throughout the pandemic, which helped many families throughout the challenging period, was on borrowed time. It ended just before the fall of 2022, sending families and students back to where they started. As of October 2023, nine states have kept the program running, including California, Maine, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Vermont. Plans for tackling the nutritional components of school lunches and universal access during a global cost of living crisis are no doubt needed. How it will all shake out is anyone's guess.