What To Know About Service à La Française, The Historical French Method Of Serving Dinner

A good meal is often an exercise in hedonism. Pairing your favorite flavors together or going back for a second helping are among the great joys in life, but no foodies did opulence quite like meals served à la Française. The now-outdated serving style was characterized by gluttony and excess — an elegant if pretentious display of wealth and social position that also frankly sounds fun to partake in. Service à la Française ("service in the French style") evolved from the practices followed by the households of the nobility in the Middle Ages (500-1500 C.E.), and it was standard mealtime practice 150 years ago. All formal Anglo-American dinners were served à la Française from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s. A classic meal in the style consisted of three courses, and until the 1700s, each course included a sweet treat.

The first course was soup (often a tasting of multiple different soups) and large plates called "relevés" stacked with roasted or stewed meats, poultry, or seafood. Common first-course dishes of the period included pasta, skewered sweetbreads, asparagus soup, pigeon bisque, filet mignon, spit-roasted whole chickens, goslings, and scalloped oysters. Service à la Française is also where the concept of hors d'oeuvres originated, but instead of being served before the meal to stoke the appetite, 1800s foodies were enjoying their hors d'oeuvres in between heavier dishes to break up the courses into more manageable sections. That might be why hors d'oeuvres translates to "outside (the) work."

Blurring the lines between appetizer, entree, and dessert

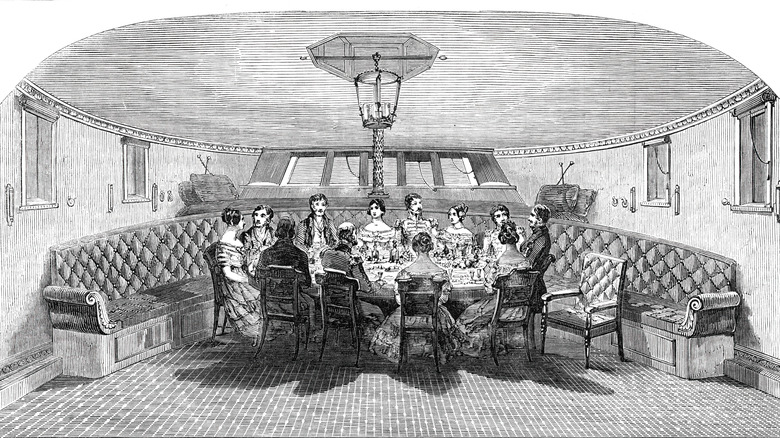

The second course in Service à la Française was the most luxurious and most varied, boasting a wide spread of salads, vegetables, and sweet and savory sides. The tables were set with the physically larger dishes lined up in a row in the center, and the smaller dishes arranged surrounding them symmetrically.

Starting in the 1800s, course two was also the point at which the cooks would bring out the main dish, aka the pièce de résistance, an elaborately designed, skillfully constructed art piece like a crown roast or seafood tower. The phrase "piece of resistance" refers to the idea that dinner guests would've had to cool it during course one to save enough room to dig into the main dish later on.

The third course was a cool-down after the workout: Small sweet bites like pastries and fruits, but also savory offerings like rabbit pâté. This is likely why the etymological origin of the word "dessert" stems from the French "desservir," meaning "to remove what has been served, to clear (the table)." It wasn't until the 1800s that dessert became a third-course thing, but once they entered the confectionery realm for good, foodies didn't hold back. Table spreads included treats from cream puffs to mince and apple pies, pain au jambon (a loaf of ham bread), hot plum pudding, macarons, custard, nuts, bread pudding with raisins, and frosted pound cake.

Idiosyncratic morsels of the era

For all its polished regality, this elevated dining style wasn't immune to period-specific quirks. The only utensil involved in Service à la Française was a spoon, and guests were expected to bring their own knives to dinner, which for male guests was usually a dagger. Knives served double duty for both slicing and stabbing individual bites of food to eat like modern diners might use a fork. At the time, this method was considered the utmost in civility, as forks wouldn't be introduced to France until the 19th century, and the dagger-impaling strategy was still classier than eating with hands alone.

Cutlery wasn't the only thing in short supply, either. Early Anglo-American diners were eating off of bowls and platters, but not plates. Instead, each guest enjoyed their meals off a trencheoir, a hardened piece of brown bread. Still, the elaborate table setting left nothing to want. They were stacked with multiple layers of tablecloths, so after each course, the top soiled cloth could be removed, revealing a fresh one below. The hostess and host were seated at the heads of the table on opposite ends and were expected to know how to carve a whole turkey or handle any other elaborate dish that would require some preparation to be served to guests.

As much a meal as an exercise in self-perpetuating social class

While these meals were seemingly built for sharing, no two plates at a Service à la Française table were the same, and not in a fun creative way. The best cuts of meat, freshest vegetables, prettiest bowls, and rarer ingredients went to the guests highest in the social pecking order. Even during mealtime, folks in 18th-century France were made to be acutely aware of their status.

Also, if more guests were coming to dinner on a given night, cooks were expected not to increase the batch sizes of each dish but to create more of them, cranking out a wider variety of offerings. That meant that not every guest would be able to try every dish, and guests with the highest social ranking got to have first pick. To avoid excessive plate-passing, top guests were seated near where the most desirable dishes would be set on the table.

For as impressive as it was, Service à la Française was also massively burdensome, requiring lots of time, space, and money. By the 1860s, the dominant style of dinner service changed to "service à la russe," which was introduced to Paris by the Russian Prince Kourakin. Still, traces of the old French style remain alive and well via the official Service à la Française (SAF), a recruitment agency that organizes and trains the most talented servers in the fine dining profession – but the hierarchical approach has thankfully remained in the past.