Belgian Vs Regular Waffles: What's The Difference?

We've all heard that the famous Belgian waffles are extra-delicious. In fact, if you ask the average American what foods Belgium is best-known for, they'd likely cite these breakfast staples (along with beer and chocolate). Thinking about the treats conjures dreamy images of thick, crispy cake with generous drizzles of Nutella, piles of juicy fruit, and clouds of whipped cream.

But we can add all those same toppings to the regular old waffles that come out of our irons in the U.S. So what exactly is it about Belgian waffles that makes them so special? As it turns out, it all comes down to the ingredients involved, the method for making each one, and how these differences affect the taste and texture of the final products. Plus, the history of Belgian waffles goes back much further than American ones. A few things changed when these treats Belgian waffles eventually made it to the U.S., leading to the distinction between the two types that you see today.

What are Belgian waffles?

These Belgian treats are widely regarded as the cream of the waffle crop. They're thick, golden, fluffy on the inside, and crispy on the outside. While Belgian waffles are often grouped together under one name in the U.S., there are actually a couple of different types in Europe: Brussels and Liège waffles. We normally think of the former as being the standard Belgian waffles, but you'll also find plenty of the latter in Belgium, which are richer and sweeter than the ones we typically eat for breakfast in the U.S.

According to Belgian lore, the Prince-Bishop of Liège was originally responsible for the tasty creations you see now. Back in the day, he asked for a pastry that included pearl sugar, a unique Belgian ingredient that was new at the time. When the sugar caramelized in the waffle iron, the result was so delicious that the prince spread the word about his new treat throughout the country. In general, though, waffles were enjoyed all the way back in 1604 in Belgium, with Brussels versions popping up around 1874.

What are regular waffles?

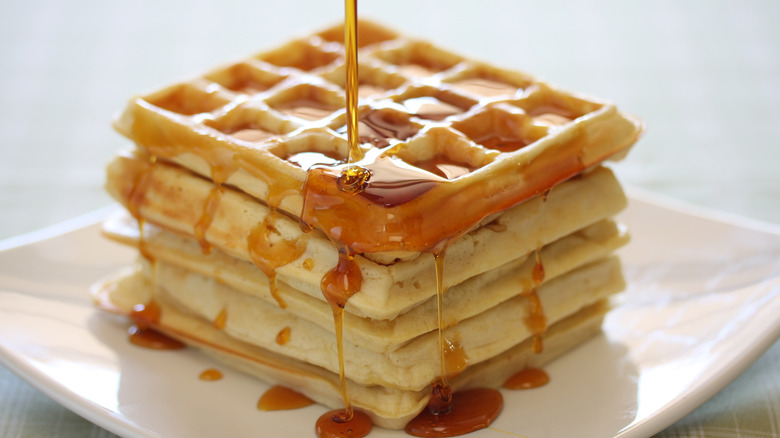

For the most part, the typical American waffle is essentially a spin-off of the Brussels waffle. According to some accounts, they were first introduced in 1962 at the World's Fair in Seattle. However, they didn't really take off in the U.S. until two years later, when the 1964 World's Fair in Queens sold them for just a dollar. The man responsible for the tasty treat at the time was Maurice Vermersch, who renamed the Brussels waffle after his home country, Belgium. Then marketed as "Brussels Waffle: A Bel-Gem Product," the street food was either served on its own or with sliced strawberries and whipped cream — without the maple syrup soak that we see today.

There are plenty of subtle waffle distinctions in the U.S. now, so you may have a slightly different definition of this treat than the next person. In general, waffles morphed from being a street food in Belgium to a breakfast dish, and we've strayed from the simpler European toppings to goodies like the aforementioned maple syrup, chicken, and ice cream. Some say that American waffles need the extra layer of flavor because they're blander on their own, while the Belgian ones are known for being delicious just the way they are.

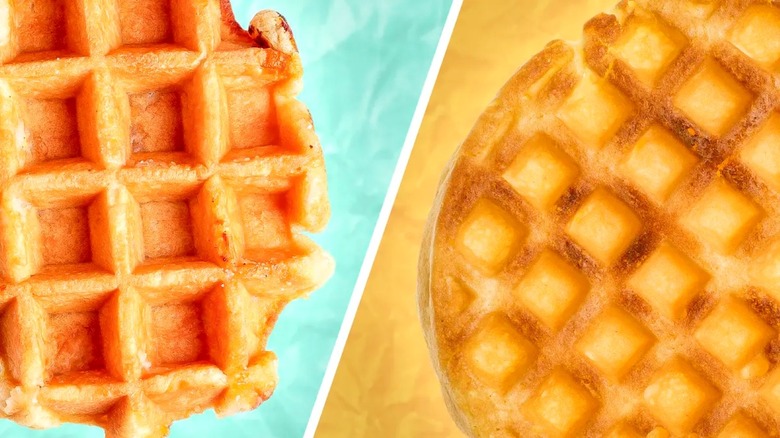

Brussels waffles have deeper pockets without all of the American toppings

If we're strictly looking at the difference between Brussels waffles and American ones, the former will almost always have deeper pockets than the latter. As any waffle-eater knows, this is ideal for trapping any toppings inside the cake so that they don't drip off the surface. And since these treats were originally eaten with your hands in Belgium as a street food (as opposed to the fork and knife typically used in the U.S.), deep pockets were crucial for minimizing the mess.

But how are these heftier waffles made? With seven inch waffle irons that contain deeper grooves. Typically circular in shape, these wide devices yield thicker results (with a standard waffle thickness of one and a half inches) — and all of that space leaves plenty of room for a fluffy interior and a crispy exterior. American irons, on the other hand, have shallower indents that result in thinner cakes overall. And yet, all that extra depth to hold toppings isn't normally used in Belgium the same way it is in the U.S. In Europe, these snacks usually stick to butter, powdered sugar, and fruit as their accompaniments, and they're frequently consumed in the afternoon rather than the morning.

Brussels waffles use yeast and a batter that sits overnight

Aside from the deep pockets and thicker width, both types of Belgian waffles deploy different ingredients than their American counterparts. Although Brussels versions are larger in size, they're also lighter and airier than regular diner waffles, and these qualities occur thanks to the yeast in the batter. Once this ingredient has been incorporated, you can let your mixture sit for either an hour or overnight, although classic Belgian bowls tend to go with the latter. Some recipes also deploy egg whites, which only add to the fluffiness of the final product. Before mixing them into your batter, you'll want to beat them until they show stiff peaks.

On the flip side, American versions don't require yeast, nor does the batter sit overnight. Instead, they generally use baking powder for leavening purposes and may even include fun components like chocolate chips and fruit mixed into the waffles themselves. While you can let your bowl sit a little before whipping out your iron to make these American treats, you can also just dive into cooking straightaway. And in general, Belgian waffles take a little longer until they're done (up to six minutes), while American ones only need about two minutes until you can dig in.

Liège waffles use brioche dough and special pearl sugar

While Brussels waffles are the closest Belgian version to what we eat in the U.S. today, we'd be remiss not to go over the unique characteristics of Liège waffles as well. Unlike the Brussels treats, these ones are more commonly consumed for breakfast. They're also sweeter and more dessert-like, with a hexagon shape illustrated in their original name: "Gaufre de Liège," in which "gaufres" refers to bees' honeycomb.

Like Brussels waffles (but unlike American ones), these treats incorporate yeast in the batter. However, they use a dough that's more similar to brioche than an American waffle. And the key ingredient here, as we mentioned earlier, is pearl sugar (or sometimes caster sugar).

As opposed to the finer grains we usually see, pearl sugar comes in larger nibs and can even add crunch to the soft texture of a waffle. But it's main purpose in Liège treats is to caramelize when it comes into contact with the waffle iron, creating crispy bits of golden sweetness and a crunchy exterior. Since they are consumed as a dessert, Liège waffles typically get a little more dressed up than their Brussels counterparts. You still won't usually see them with maple syrup like in the U.S., but you may find goodies like Nutella and cookie butter to drizzle over the top.