15 Chinese Egg Dishes You Should Try At Least Once

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Eggs are a staple of cuisines around the world for a reason. They're accessible, affordable, and pretty easy to cook. Plus, there's so much you can do with them! Boiled, scrambled, fried, souffléd — not to mention the hard work eggs do when giving structure to baked goods or emulsifying sauces. The incredible egg, indeed.

It comes as no surprise that eggs feature heavily in Chinese cuisine. Researchers have long believed the domestication of the chicken occurred in Southeast Asia, India or China (the earliest chicken remains were excavated in central Thailand and are estimated to be around 3,500 years old) and where there are chickens, there are eggs.

There are dozens of traditional and American Chinese dishes that highlight eggs, from century eggs to egg foo young, and they're all worth a taste. Chef Calvin Eng — chef and owner of Bonnie's in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and author of the upcoming Cantonese American cookbook "Salt Sugar MSG" — walked us through some of his favorites. From dishes his mom makes to Chinatown must-tries and even some egg dishes you might have to go to China to taste, these are the egg dishes from China you've got to try at least once.

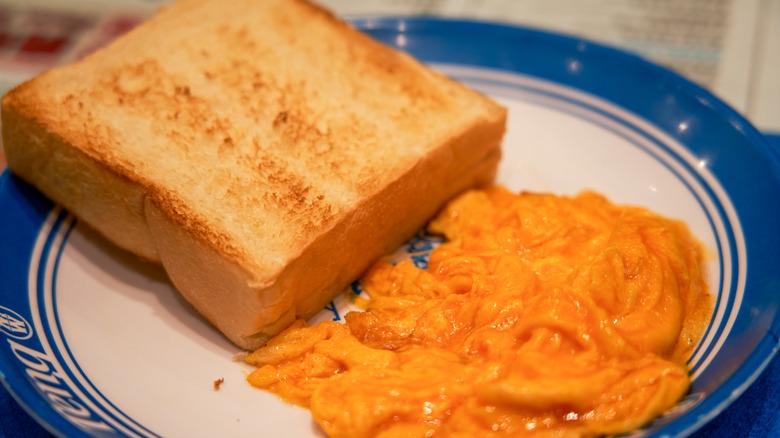

Tomato egg stir fry

We've all been there. It's time for dinner, and you open the fridge to find ... nothing. There's no moment more perfect for a couple of eggs. Add some tomatoes and serve it over rice, and you've got yourself a meal.

Tomato egg stir fry, or jia chang cai, combines soft-scrambled eggs with acidic tomatoes, a pinch of sugar, and aromatics (scallions, garlic, and ginger are popular, as is Shaoxing wine). This home-style dish is also served in cafeterias and some restaurants, and is a sweet-sour-savory dose of nostalgia. The secret is to scramble the eggs until they're just barely set, remove them from the pan, and then cook the tomatoes and aromatics. Once the tomatoes are ready, you then add the eggs back to the pan to finish cooking and marry the flavors.

Egg foo young

Egg foo young is a Chinese American classic, and is a staple on menus at Chinese restaurants in the United States. While the exact origins are unclear, an omelet-style patty of eggs and chopped vegetables topped with brown gravy has major Midwestern appeal.

Unlike a French or American omelet, the eggs in egg foo young are pan-fried into a browned, crispy patty. Wok cooking creates almost a deep-fried effect, allowing the eggs to puff up and turn golden in the oil. A combination of ingredients, including chopped chicken or shrimp and vegetables, adds texture and flavor to the eggs.

And you can't forget the gravy. Unlike the flour-based gravy you'd find ladled over chicken-fried steak or a plate of biscuits, this gravy uses cornstarch as a thickener. Combined with water, sesame oil, and soy and oyster sauces, the brown gravy is glossy and viscous, adding an extra savory note to the dish.

Golden fried rice

This list would be incomplete without fried rice, but no fried rice highlights eggs quite like golden fried rice. While eggs are a common fried rice ingredient, golden fried rice is different.

Each grain of rice has a vibrant yellow hue, but the color doesn't come from saffron or turmeric. The rice is golden because it is coated in unctuous, savory egg yolk. There's no hiding the egginess of this dish!

Cooked and cooled rice is combined with raw egg yolks, stirred thoroughly together until every grain is entirely covered. Then, the rice is cooked in a very hot wok — the key to any successful fried rice dish. The fat from the egg yolk helps prevent the grains from clumping together, but this dish is anything but dry. In fact, in Chinese restaurants, you'll often see golden fried rice plated in a dome shape by packing the rice into a bowl before inverting it onto a plate.

Hong Kong egg scramble

Not all scrambled eggs are created equal, and Chinese cuisine has a plethora to choose from. Chef Calvin Eng sings the praises of the Hong Kong egg scramble, which he first tasted at a Hong Kong cha chaan teng (a tea restaurant or diner). "The eggs were soft and pillowy, custardy and light. They were unlike any other scrambled eggs I had experienced before," Eng describes. He loves the eggs so much, he figured out how to make them himself and even included a recipe in his cookbook.

That unique texture comes from a few extra ingredients that give the humble egg some oomph: evaporated milk (the plain stuff, not sweetened condensed milk) and cornstarch. "The evaporated milk adds a nice bit of fat that gives the eggs a silkier and richer texture and taste," says Eng. The starch is used to make a slurry with water (a common technique for Chinese sauces) that keeps the eggs as light as they look in the pan. Is it scrambled eggs? Is it a custard? You'll have to try it for yourself.

Lu dan

If you've ever enjoyed deviled eggs or egg salad, you know that hard-boiled eggs are an incredible canvas for flavor, and that applies to Chinese cuisine, as well. For lu dan, meaning "braised egg" in Taiwanese, that flavor comes from an umami-rich braising liquid with soy sauce at its base. Lu dan are often eaten as a snack or served over rice or bowls of noodle soup. Some lu dan are made with pork braising liquid for an extra rich (but not vegetarian-friendly) flavor.

Eggs are boiled, cooled, and peeled before being placed in cold braising liquid. A shorter cooking time will result in jammy egg yolks, while longer cooking will give you egg yolks that are more firm — especially when chilled.

The braising liquid is made with soy sauce infused with a variety of spices (think cinnamon, star anise, and Szechuan peppercorns). The eggs marinate for at least 24 hours, giving the outside of the egg a light brown hue and infusing the boiled whites with flavor.

Century eggs

You've probably heard of century eggs, but have you ever eaten them? These eggs are a true lesson in preservation. It may not take an actual century to make them, but it does take a few months from start to finish, all made possible by ash, salt, and quicklime.

Making century eggs has evolved from a matter of preservation to a quest for flavor. The alkaline mixture the eggs are covered in causes the sodium levels inside the egg to rise, darkening the colors and turning the egg proteins into a dense, shining jelly.

The eggy, sulphuric aroma and dark appearance may be a far cry from the scrambled eggs at your local diner, but this delicacy is worth a try. Century eggs are served hot or cold, often with congee or over chilled tofu. The flavor is funky and rich, and often not as intense as you'd expect based on the eggs' appearance. All the more reason to give this eye-catching Chinese egg dish a try. Just be sure to get your eggs from a reputable source, as some producers use lead to speed up the curing process, which is definitely not delicious.

Tea eggs

Tea and Chinese culture go hand-in-hand, and so do tea and eggs. Tea eggs are an on-the-go snack sold by street vendors in China that pair boiled eggs with the tannic flavor of tea. The whites of the eggs are marbled with brown, stained from where the tea leaked through the cracked egg shell. They're as elegant to look at as they are easy to make, meaning you can easily customize the eggs themselves to your liking, like chef Calvin Eng does.

His mom would buy eggs at a shop in New York's Chinatown for an afternoon snack. "The ones she bought had chalky yolks that turned a pale shade of green from a long soak in the simmering soy-spiced tea mixture," Eng recalls. He would eat the whites while his mom ate the yolks, though these days, he cooks his eggs less so the yolks are bright and jammy instead. After cooking the eggs and cracking the shells, Eng soaks them in a combination of black tea and soy sauce, seasoned with ginger and whole spices.

You could also give tea eggs a Southern twist by turning them into tea-marbled deviled eggs. After soaking the eggs, split them in half and remove the yolks to make a creamy, spiced filling.

Silken eggs

No, it's not tofu. Chinese silken eggs — also called steamed egg custard — is a smooth, velvet dish that looks a lot like flan or panna cotta, though there's no dairy or gelatin here.

The eggs are meticulously beaten with water and salt, then carefully strained to remove any stray egg whites. The mixture is skimmed to remove every last bubble, then is tightly wrapped in plastic to keep stray moisture out before gently, slowly steaming. Toppings and sauces vary — some even have meat or vegetables steamed inside — but the measure of success is always that soft, subtle jiggle and a perfectly smooth top.

For chef Calvin Eng, writing a recipe for steamed egg custard wasn't as straightforward as asking his mom. "She rarely measures ingredients, so her technique for this dish utilizes eggshells to measure the proper ratio of liquid to egg to yield the most velvety-smooth consistency," he reveals. He loves the versatility of the dish, from serving it simply with rice like his mom would to slipping pieces of poached lobster into the custard before cooking.

Egg drop soup

Nothing warms the body and soul quite like egg drop soup, making this a Chinese egg dish you've got to try ASAP (if you haven't already). It's the perfect way to start your meal at a Chinese restaurant, and is also incredibly easy to make at home.

The base of egg drop soup is chicken broth — though you could use vegetable broth to make a vegetarian version at home. A cornstarch slurry is used to make the soup more viscous. But the real star of the show is the egg.

Once the broth is hot and the cornstarch has done its job, the soup is stirred to create a whirlpool in the stockpot. Beaten eggs are then poured into the moving liquid, with the speed of the pour determining how thin or thick the ribbons of egg are.

Egg drop soup is often garnished with scallions, corn, or diced carrot and topped with crispy wonton strips. Choose your own adventure and enjoy!

Dan jiao

Love dumplings? You won't want to miss dan jiao — dumplings where the wrappers themselves are made of egg that is carefully cooked in a hot ladle and wrapped around a pork filling. These bright yellow dumplings resemble gold nuggets, making them a must-have during Chinese New Year banquets in southeastern China to ring in a prosperous year.

Unlike dumplings wrapped in thin and stretchy dough, dan jiao are delicate and particularly tender. They also require meticulous construction, which is why they can be hard to find on restaurant menus unless you know where to look. A heated ladle is heated and greased, then the beaten eggs are poured in. As the ladle cooks the eggs, a scoop of filling is added to the middle before the super-thin omelet is folded to encase the meat.

If you do stumble upon dan jiao at a restaurant (or take on the task of making them at home), you'll be rewarded with eggy dumplings that are perfect simmered in soup. Eager home cooks should seek out a stainless steel wok ladle, like this one from Sunrise Kitchen Supply, for the best results.

Jianbing

What is it that makes eggs such a great breakfast food? Is it how quickly they cook? How versatile they are? How seamlessly they pivot from one flavor profile to the next? The nutritional value in such a tiny package? Whatever the reason, eggs at breakfast are here to stay, and Beijing's popular street food, jianbing, should be on your list.

Jianbing is a thin crêpe made of a wheat or mung bean batter, filled with egg, herbs, hoisin sauce, and crispy wontons. It's a grab-and-go breakfast to rival your favorite breakfast burrito, a symphony of flavor and texture that will start your day right.

Traditional jianbing keeps the fillings simple, but it can also be amped up with additional fillings like sausage, chicken, or even Peking duck. The key is to enjoy it fresh, as soon as it comes out of the pan. This ensures the perfect balance between soft crêpe, crispy wonton, and crunchy fillings.

Mooncakes

Every year during the Chinese Mid-Autumn festival, mooncakes seem to come out of the woodworks. While the origins of mooncakes are shrouded in myth, mooncakes are said to have played a role in the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty in the 14th century, when the revolutionaries hid messages outlining their plans in the dense filling.

These intricately molded pastries, which represent unity and good luck, are traditionally filled with a dense, sweetened paste of lotus, nuts, or seeds wrapped around a salted egg yolk — the yolk symbolizing the autumn moon. The exterior is a thin, delicate pastry topped with a shiny brush of egg wash. Mooncakes are a combination of sweet and savory, with richness from the egg yolk center.

The most eye-catching aspect of a mooncake is its appearance. The salted egg yolk is wrapped in filling, then surrounded with a thin dough wrapper. Each cake is then pressed using a mold, giving each mooncake its ornate shape and pattern.

Liu sha bao and nai wong bao

Much like a runny egg yolk is the highlight of a perfectly fried egg, an egg yolk-based filling can turn a normal steamed bun into a star. Liu sha bao and nai wong bao are two such buns; must-try items on any dim sum restaurant's dessert cart.

Liu sha bao, known as a flowing sand bun, has a sweet and savory filling made of salted duck egg yolk, custard powder, butter, milk, and sugar. When you tear the bun open, you're greeted with a vibrant yellow filling that is equally creamy and gritty due to the combination of custard powder and crumbled egg yolk. The molten center is reminiscent of Hong Kong-style French toast, a dish that chef Calvin Eng features on his restaurant's brunch menu. "In Hong Kong, it's super common to find the middle layer hollowed out and filled with peanut butter or Ovaltine spread," Eng describes. His cookbook features a version with a liu sha bao-style salted duck egg custard filling.

Nai wong bao is liu sha bao's less gritty cousin. The filling uses fresh eggs, and is creamy but more solid than the runny interior of liu sha bao. Both require some patience to make, as the dough needs to proof properly and then be carefully steamed. No matter which you choose, these baozi are delicious ways to end your dim sum meal.

Daan tat

If there's one thing you'll spot in the case of every bakery in Chinatown, it's daan tat, or Hong Kong egg tarts. These palm-sized treats feature a flaky pastry filled with golden custard that's reminiscent of Portugal's pastel de nata, though there are a few key differences.

First, daan tat has a smooth and shiny top, unlike the dark blisters on top of pastel de nata. Second, daan tat's custard filling is more eggy, whereas the custard in a pastel de nata is accented with vanilla and cinnamon. Third, the crust itself. For daan tat, the laminated pastry is traditionally made using lard or shortening instead of butter. The dough is layered with an oil dough (a combination of fat and flour) instead of only fat as you'd see in a European-style puff pastry dough. The crust is more tender and crumbly, versus the crisp and flaky crust of a pastel de nata.

Daan tat are the perfect single-serving dessert for the end of a dim sum meal (at about 3 inches across), but they're also a portable treat. Next time you spot Hong Kong egg tarts at a Chinese bakery, grab one to go and eat it as you walk down the street — no fork necessary.

Steamed sponge cake

Steaming is probably not the way you usually make a cake. Baking? Yes. Water bath? Sure. But do you even have a steamer that can hold a cake pan? (If all you have is a folding steamer basket, a flat stainless steel steaming rack that fits in your biggest pot will open up a whole world of steaming for you.)

Back to the cake. Chinese steamed sponge cake is a fluffy, spongy cake often served as dessert at a dim sum meal. It's egg-based, just like angel food cake, but it uses the whole egg instead of just egg whites so the flavor is more rich and the texture more moist. Chef Calvin Eng loved making this cake as a kid. "I made a version of this cake so often that my grandma at one point had to firmly request that I stop making it for her," he recalls.

Some recipes also include a levain to give the cake extra lift. You can spot the difference by looking closely at your slice. If it is striped with air pockets, that's a sign of fermentation. Uniformly fluffy with no bigger bubbles? That's baking powder.