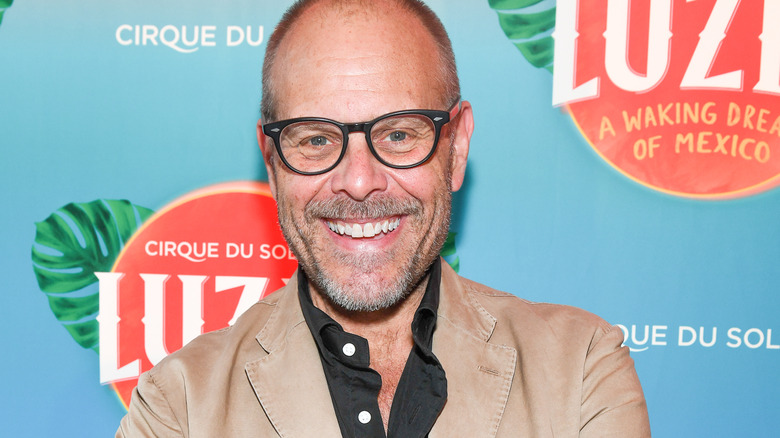

The Seasoning Myth Alton Brown Can't Stand

According to Alton Brown, jumbo shrimp is an oxymoron. If you parse the culinary term, you'll get what Brown means. "Jumbo" means large, while "shrimp" means really small, and yes, it refers to extra-large shrimp (another oxymoron), but, as Brown told Tasting Table in an exclusive interview, the two words spliced together make no sense. Another culinary term that Brown detests is "dry brine," because, as he stated, "There's no such thing." Such a bold opinion does give one pause, as dry brining is often preferred over wet brining for certain cuts of meat. Brown, however, is nothing but exact, and he insists that the more correct term for what is called a dry brine is a "cure."

It's easy to confuse the two, as they have similar components: salt, spices or seasonings, and, oftentimes, sugar. According to the USDA, the ingredients for a cure also include potassium nitrate and nitrites, which add the characteristic color and flavor to certain meats, like ham, and prevent the growth of harmful bacteria. A dry brine and a curing mix are applied identically by rubbing the salted mixture directly onto the meat and then refrigerating it for a specific number of hours. So despite the slight difference in ingredients, it's clear that Brown is right in calling a dry brine a cure. But Brown also thinks the term "wet cure" is inaccurate because its effect on meat is totally different from what a dry cure does.

The reasons why a cure is better than a brine

The technique for a so-called "wet cure" is the same as brining a turkey. As Brown noted, a brine exchanges seasoned liquid with the water in the animal's protein cells and thus keeps the meat juicy. Despite popular belief, adding flavoring to a brine, like seasonings, herbs, and spices, actually does very little if anything to flavor the meat, and in effect, you're simply over-saturating the poultry, which affects its taste and texture. Certainly, brining a turkey has a lot of fans, but what's good for the bird isn't great for the beef, especially a pricey holiday rib roast or prime rib when you want a crispy browned sear that can only come from properly curing the beef.

The only way the Maillard reaction works is by removing all surface moisture from the meat, which is what a liberal sprinkling of Kosher salt does. The salt pulls out the meat's moisture, and by a chemical reaction, the meat's muscle dissolves, which then allows the salted juices to be reabsorbed, rendering a naturally flavorful roast and a moisture-free exterior that's ideal for searing. A cure isn't just for beef; with a little baking soda added, it works wonders in creating snap-crackling roast pork skin and chicken or turkey skin. So ditch the fancy foodie terms that irk Alton Brown and never call a cure a dry brine again.