10 Easy Molecular Gastronomy Tricks To Elevate Your Home Cooking, According To A Chef

Molecular gastronomy is generally recognized as the meeting of science and culinary arts. It's the realm of mad hatter fine dining chefs such as Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck and Grant Achatz of Alinea, and its intimidating name, scientific approach to cuisine, and demanding culinary precision make it something rarely considered for home cooking. At Tasting Table we even shared a warning from Albert Adrià, brother of Ferran Adrià and creator of El Bulli's famous liquid olive spherification, who advised against even trying molecular gastronomy at home because the equipment is too specialized, and the skill required is too advanced for most home cooks. However, this isn't necessarily the case.

In 2024, I completed a master's degree in Culinary Arts, Innovation, and Kitchen Management at the European University of Hospitality and Tourism in Sant Pol de Mar, a village in Catalonia. Given the school's proximity to Roses — the location of El Bulli, the restaurant that put molecular gastronomy on the map back in the early 2000s — it's no surprise that molecular gastronomy featured heavily in the syllabus, and I was fortunate enough to study and practice a wide range of molecular techniques, from cooking with liquid nitrogen to creating my own spherifications. Following this, I gained experience in Michelin-starred kitchens in Europe where molecular gastronomy techniques were used to surprise and delight customers. In this article, I'll explain some molecular tricks that require little specialist equipment or culinary mastery to pull off at home.

Reinvent A Dish With Deconstructed Plating

The concept of deconstruction in cooking involves identifying the component elements or flavors of a well-known dish, then presenting them in a way that is different and original to how the dish is typically served. There are plenty of unusual examples of deconstruction in the world of fine dining, such as Grant Achatz's Peanut Butter & Jelly, which turns the familiar flavors of jelly, peanut butter, and bread into a playful amuse bouche where a grape with the stem left attached is coated in peanut puree then wrapped in brioche. The result is decadent and creative, but with a similar flavor profile to a classic American PB&J sandwich.

There is no reason why you can't introduce deconstruction to your home cooking to reinvent well-trodden classics as something new and intriguing. A lasagna, for example, can be reimagined as a deconstructed lasagna soup with similar ingredients to a typical lasagna. What's more, the deconstructed version takes less time to prepare, is filled with all those delicious tomato, cheese, and pasta flavors and textures, and requires just one pot, therefore saving on washing up.

Many desserts can easily be deconstructed, too. A traditional British trifle contains layers of raspberry Jell-O with sherry-soaked sponge cake, custard, and whipped cream. However, you could present this as a circular sponge cake sat in a tangy sherry wine reduction, topped with a layer of set Jell-O, with dots of thick custard and whipped cream on top. Voila: Your trifle just became a showstopping "trifle cake."

Make Delicious Powders With Just Your Oven

Beyond simply rearranging elements on a plate, one technique that's popular in molecular gastronomy and more broadly fine dining is creating potent flavored powders. Not only is this technique relatively straightforward to do at home, it is incredibly versatile, and can help you cut down on food waste by turning unwanted offcuts and leftovers into delicious, long-lasting, and flavor-packed powders.

The concept is simple: Select an ingredient, dehydrate it (fine dining kitchens usually use a dehydrator to do this, but setting your oven to the lowest setting will achieve similar results), then once it's completely dry and brittle, use a blender to turn it into a fine powder. If you're being fancy, you can even pass the powder through a fine sieve to make sure it's a perfect fine dust.

Powders can be used in savory and sweet dishes to give an extra whack of flavor. I have made powders from shrimp heads and shells, dehydrating these and then blending them into a dust that I used to coat peeled shrimps lightly cured in a sweet and sharp lime blend. The result is a bite with the unique texture of cured prawn, combined with the shrimp stock flavor of the prawn dust. Citrus peels can also be turned into a potent powder that works for both sweet or savory dishes. However, because they contain lots of natural oils, you'll first need to boil them in water multiple times to leach out the oils.

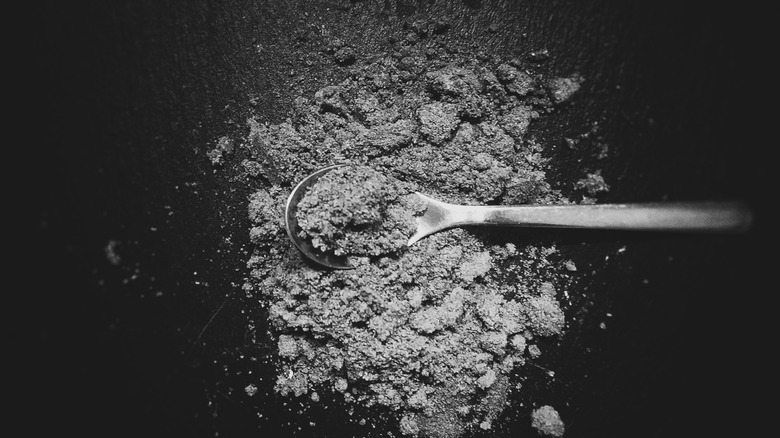

Elevate Dishes With Vegetable Ash

Not too dissimilar from the process for making powders, vegetable ash can have a dramatic visual impact when used cleverly, and in moderation it can add depth and complexity to dishes, making it a worthwhile technique to employ at home. Best of all, it's easy to make and is a perfect way to turn leftover vegetable peelings into a shelf-stable, bible-black ash. Simply put your vegetable peelings into a hot oven in an oven-safe pot or tray covered with a lid or aluminum foil, and leave them until they've dried and blackened completely. Carefully pass the blackened peels into a blender and blitz, then pass through a fine sieve to make sure the texture and size of the ash is consistent.

While training at Aponiente, a 3 Michelin-starred restaurant in Andalucía led by "the chef of the sea" Ángel León, I helped prepare a dish called "cephalopods roe," a creamy onion sauce with a dollop of flavored tapioca and squid ova served in a bowl dusted with a thin layer of onion peel ash. The plating makes the dish look like a sketch from a biology textbook, with the black-speckled ash layer creating a frame for the unusual, powerful flavors of the main components. At home, use a tea strainer to dust a plate with ash, part-stir a pinch to softened butter before setting into an ash compound butter, or mix a little with salt and use it as a steak rub.

Make Faux Caviar From (Almost) Any Liquid

Faux caviar is a well-known molecular gastronomy technique that's frequently used in fine dining restaurants around the world. It involves turning a flavored liquid into small, firm caviar-sized balls thanks to the addition of agar agar. This technique differs from Albert Adrià's famous liquid olive spherification because faux caviar is solid, whereas the reverse spherification method employed by Adrià for his liquid olive creates a gel membrane with a liquid center. However, fake caviar is thankfully much easier to carry out at home: All you need is a flavored liquid of your choice, cold vegetable oil, and agar agar powder.

To make faux caviar, first put enough vegetable oil into the freezer to fill a tall beaker or glass. This will chill the oil, but it won't set. Next, weigh a flavored liquid, pour it into a small pot, then add 1% of the liquid's weight in agar agar powder to the liquid and bring it to a boil, stirring well. Keep it boiling for one to two minutes, then remove from the heat and allow it to cool a little, before using a pipette (a sauce bottle with a nozzle will do) to release droplets of the liquid into the cold oil. The lower temperature causes the liquid-agar mixture to set in drops that gather at the bottom of the oil. Uses include soy sauce caviar for elevated sushi, balsamic caviar for a salad, or fruit caviar for a dessert.

Create Flavorsome Gels With Agar Agar

The wonders of agar agar don't end with faux caviar. This inexpensive and vegan gelling agent is particularly useful in creating edible gels, a fine dining staple. Gels are particularly useful for elevating plating, allowing you to present what would normally be a solid food or a runny sauce in a smooth gel form, which is perfect for dotting onto plates with a piping bag. You could reimagine a pan sauce for steak as meaty gel dots, or top a cake with dots of perfectly structured lemon curd or raspberry gel.

The process for making gels from agar agar isn't overly complicated. As with faux caviar, you first need to create a flavorsome liquid. For example, an olive gel starts with a strained liquid of blended olive (black or green, depending on your preference) mixed with a little of the olive's brine. Then add 1% to 2% of the weight of the liquid in agar agar, mix well and bring to the boil for one to two minutes. Here's where things vary from faux caviar: Instead of dripping into cold oil, leave it to cool and set in the fridge. Once it's fully set, put the firm, gelatin-like gel into a tall beaker and blend well with a hand blender. It will magically change from a hard gel into a soft gel! Pass this through a fine sieve once more to make sure it's a consistent texture, then scoop into a piping bag and use.

Make Edible Flavored Air

Soy lecithin is an interesting culinary ingredient with a variety of applications. You'll often see it included in the ingredients of store-bought chocolate and baked goods, as it helps to extend shelf life and can make chocolate more malleable and easier to work with. It's also an excellent emulsifier, so you can use it in your kitchen to help make sure your homemade mayonnaise binds together perfectly, or even to make a vegan mayonnaise since eggs contain lecithin, which you can replace with vegan soy lecithin instead. You can also use soy lecithin at home to turn fatty liquids into edible flavored air, a truly molecular bit of culinary magic.

To make an edible cheese air, for example, combine warm water with plenty of strong grated cheese, like parmesan. You can add herbs like thyme to this as well for added complexity. Allow the mixture to steep, so the parmesan (and herbs, if you so choose) can infuse into the water, then strain the mixture. Then add 0.5% to 1% of the weight of your liquid in soy lecithin powder, blend it well with a whisk and heat the mixture again, but don't let it boil. Once warmed to about 140 degrees Fahrenheit, pour the mixture into a tall beaker and blend with an immersion blender, tilting the blender to incorporate as much air into the liquid as possible. A raft of stable, cheesy bubbles will form: Scoop up spoonfuls of bubbles and drop them onto your desired dish.

Make Solid Foams

If you want, you can go a step further and create solid foams without much more complexity than creating edible air. All you need is soy lecithin, a disposable plastic cup, and your freezer. To make solid foams, you first need to create stable air bubbles from your liquid using the process for creating edible air. Once you have plenty of bubbles on top of your soy lecithin-flavored liquid mixture, scoop these into a clean plastic cup. Although the bubbles are relatively stable, it's worth taking care not to disturb them too much as they can still collapse when moved around or compressed.

When you've filled your cup, cover it with plastic wrap and transfer it to your freezer. The soy lecithin should keep the bubbles from collapsing for long enough that they will freeze in bubble form. After about an hour, your bubbles should be frozen solid. You can then carefully cut down the side of the plastic cup to release it from the bubble block, and then cut this into your desired shape for plating. This technique allows you to present familiar flavors in a striking way on the plate, and works particularly well as an element in a creative dessert.

Transform Oils And Fats Into Powder With Maltodextrin

Another fascinating starch powder that's used in molecular gastronomy is maltodextrin, which can turn liquid fats into light, flavorful powders. Maltodextrin can be bought online easily enough, but it's worth being aware that it's an incredibly light powder and, depending on the fat content of the liquid you're trying to turn into a powder, you may need to use quite a lot of it, so it's easy to use it up quite quickly.

The process for making powdered fat with maltodextrin is actually very straightforward. Add a generous amount of maltodextrin powder to a clean food processor, then add your liquid fat on top and blend. It's best to add the fat a little at a time, blending in between. You will see your fat be absorbed into the maltodextrin powder, causing it to take on a more crumbly, sandy consistency. If you're using a colored fat, such as a deep yellow extra virgin olive oil, you will see the powder gradually change color as it absorbs more of the fat. This process can be used to make bacon fat powder, peanut butter powder, olive oil powder, or even white chocolate powder for a dessert. Best of all, maltodextrin melts almost immediately on contact with liquid, creating a magical solid-to-liquid transformation when consumed.

Create Puffed Ingredients With A Microwave

Not all molecular gastronomy requires fancy ingredients and specialized equipment. With a little creativity, a microwave can turn everyday or unwanted ingredients into texturally intriguing "puffed" foods, which will elevate an everyday dish into something a little more fancy. It does this thanks to its ability to dehydrate and heat ingredients rapidly, the same effect which causes corn kernels to puff into popcorn in the microwave.

One of my favorite uses for microwave puffing is oil-free chicharrones, or puffed pork rinds. They're a great way to turn unwanted pig skin from a roasting ham into a savory snack. Remove the pig skin and boil it for an hour or until it's soft, cut or scrape all the fat from the underside of the skin, then dehydrate it in your oven on the lowest setting until it's translucent and completely dry. Once dehydrated, shatter the skin into small pieces, but take care not to hurt yourself as it can be very hard. Pop these pieces in your microwave and heat on full power for 30 to 60 seconds at a time until they puff up, then season them with salt and paprika and serve. The same can be done with rice: Cook the rice as normal, dehydrate on a baking tray in the oven, then puff it up in your microwave for a crunchy puffed rice that works as well on desserts as it does in milk as a homemade cereal.

Cook With A Makeshift Sous Vide

If there's one bit of fine dining technology that can truly elevate your home cooking, it's sous vide. Sous vide is a water bath set to a controlled temperature, which allows you to cook any food that's sealed inside food-safe plastic bags with absolute precision. In professional kitchens, it's common to see expensive commercial sous vide machines that circulate water while maintaining a precise temperature, and food being cooked sous vide is usually vacuum sealed into sous vide-specific plastic bags using a professional vacuum sealer. However, the truth is that all this expensive equipment isn't necessary to cook sous vide at home.

You can make your own makeshift sous vide with just a thermometer, a large pot, and a food-safe sealable plastic bag. Attach your thermometer to the side of the pot, then fill it halfway with hot water. Now add cold water until the thermometer reads the desired temperature. For example, a sous vide at 130 degrees Fahrenheit will produce a perfect, medium-rare steak. Place the steak, some butter, and aromatics into your sealable bag, and slowly lower this into the bath with the opening above the water level. The water pressure will force the air out of the bag, and you can then seal it and attach it to the side of the bath with a clip. After one to three hours, depending on thickness, remove the steak and finish in a hot pan.