From Agave To Your Glass: Everything You Need To Know About Making, Drinking, And Actually Enjoying Tequila

CORRECTION 2/24/25: A previous version of this article stated that gold tequila is a type of añejo; gold tequila is made by blending blanco tequila with an aged tequila, therefore it cannot be categoritze as añejo.

Rapidly growing in popularity, it seems tequila has once and for all shaken its '80s image as something drunk solely by spring breakers and hard-partying musicians on a bender. And while it's now much more common to see a tequila flight or high-end bottle on the shelf at a trendy bar — meant to sip, not shoot — there is still a bit of mystery surrounding exactly how the spirit is made and how to drink tequila for the best experience. (Believe me, there is a wrong way to drink tequila.)

While I have never outright disliked tequila, I usually order mine in cocktail form and only recently started to discover just how much the spirit has to offer. With a few tastings under my belt (and a few nicer tequila bottles stocking my home bar), I was thirsty to learn more. And as luck would have it, Patrón invited me to visit its distillery in Jalisco in Mexico for a master class on all things tequila.

Common tequila myths you shouldn't believe

First, let's get some common misconceptions out of the way: Tequila is not vodka that's been flavored and (sometimes) colored. It's its own unique spirit distilled from blue Weber agave. And while some bottles of tequila may be "cheap," it's not cheap to make. Agave must grow for around 10 years before it's ready to be harvested and can only be farmed in specific regions of Mexico to be used in tequila production.

Tequila does not have more alcohol than, say, gin, whiskey, or vodka, and despite what Anthony Bourdain might have believed, it is not more likely to give you a hangover, either. (If you're looking for something to blame, turn your attention toward the way — or volume at which — you're drinking the stuff.)

Is tequila the same thing as mezcal? It's complicated ... or maybe not. Opposite of what you may think, all tequila is a form of mezcal, but not all mezcal is tequila. This is because mezcal can be made from multiple types of agave, while tequila can only be made using one kind.

The basics: What is tequila?

Tequila production is closely regulated by the Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT). There are five official varieties of tequila that all start in the same place: an agave field in the states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Nayarit, or Tamaulipas in Mexico. From there, the agave is processed using a few different methods, which impact the final taste, aroma, color, and body of the spirit. Although some brands will "cheat" a bit with additives to make the tequila they're selling seem more similar to a higher-end bottle, they are ultimately the same product. There are a few signs to tell if there are additives used, which we'll dig into later, but for the most part, you can trust your gut. If it seems too good — and cheap — to be true, it probably is.

As stated above, tequila is made with blue Weber agave only. There are two standards for tequila: mixto (which is made with a minimum of 51% agave; the other 49% can be distilled from anything, though it's often sugarcane) and 100% blue Weber agave (which must contain less than 1% of other ingredients).

What is agave, really?

Though it may look similar to aloe, agave is more closely related to asparagus. There are over 200 varieties of the succulent, with 75 of those being grown in Mexico, and one — blue Weber — used in the tequila making process. Agave is grown by farmers who are often in contract with specific brands. The farms must register with the CRT, which keeps track of how many plants each has, the location of these plants, and the location of the farm. Any agave not registered cannot be made into and sold as tequila.

Agave farms are located in the highlands or the valleys, which have different soil and climates. Like wine grapes, agave has a natural terroir that is impacted by where it's grown. For example, the soil in the highlands is made of iron oxide-rich red clay. Not only does this give the earth its vibrant hue, but it also adds acid, which, in turn, creates sweeter agave.

Most agave plants are created through asexual reproduction, not grown from seed. This is because it takes longer to allow an agave plant to flower and drop seeds than it does for the plants to reproduce on their own. (Flowering agave plants are also unsuitable for tequila production because the flower saps the sugar while growing, resulting in bitter tequila. If a flower begins to grow, it is cut off.) The mother plant shoots off little pups underground, and after two to three years, those smaller plants are dug up and replanted in their own space, ready to start creating pups of their own.

Agave is grown for 10+ years before harvesting

Agave plants are harvested by jimadors, who pass their knowledge down through apprenticeships. The heart of the plant is the part used to make tequila. (If you need a visual, think of an artichoke.) The agave must be fully grown before it can be harvested, which takes on average 10 years: two to three as a pup, seven or more to mature in their own space. Replating and harvesting agave must be done by hand, as the hearts' size can vary greatly.

There are a few cues the plant is fully mature: The bases of the leaves begin to turn yellow, and the leaves in the center of the plant are shorter than the exterior ones. Jimadors also measure the plant's sugar using a refractometer, the same way sugars in hard cider and wine are tested. To do this, they count down three spots in a spiral and extract a sample. If the sugars are at the right level (industry standard is 15-18 brix; Patrón's average is 25, and Jose Cuervo's is 20-30), it's ready to harvest.

If the agave is fully mature, a jimador will chop off the exterior leaves, which can add methanol and bitterness to tequila. The specific cut they use can vary, as tequila companies have different standards and jimadors prefer different techniques. (At Patrón, for example, all jimadors are trained to do the same cut, shaving off as much of the green parts as possible.) Most producers also limit the amount of red spots a heart can have, which indicate the plant was overmatured.

Brick ovens vs autoclaves: the pros and cons of each roasting method

After the agave hearts are harvested, they're sent off to a distillery. From these batches, samples are taken to test the sugars and look for red spots or other flaws that could impact the final product. This must be done quickly, as agave that isn't cooked after a few days (Patrón says the hearts it uses never sit for more than two) will begin to break down, lose sugar, and can even start growing new leaves.

Raw agave hearts are chopped up into smaller pieces before roasting to guarantee uniform cooking. There are two types of ovens typically used: brick and autoclaves. The distillery chooses which it will use based on its needs. Brick ovens are slower but easier to control; autoclaves are quicker and can process larger batches but are more prone to uneven cooking. Patrón uses brick ovens and shared that each batch of agave hearts cooks for 79 hours; Jose Cuervo, which also uses ovens, cooks its hearts for 36-40 hours; autoclaves can roast a batch of agave in as little as seven.

Milling the roasted agave hearts

Once the agave is roasted to perfection, it's ready to be milled. The sugars of raw agave are too complex to properly taste, but roasting breaks them down into simpler molecules. Undercooked agave has a lighter color (raw looks similar to jicama or sugarcane), isn't very sweet, and is watery. Overcooked agave is syrupy, a little bitter, and doesn't contain much liquid at all. The perfect roast is plump and sweet and has a flavor similar to raisins.

Before milling, the roasted agave is cooled slightly and then shredded. There are two milling methods: tahona and roller. Many companies, such as Jose Cuervo, use just one of the two methods for a batch of tequila (roller is most popular), while others, like Patrón, use a mix of both, as they produce different results. More traditional than roller mills, tahona mills are made of stone, which imparts earthy, mineral notes to the agave. Neutral, metal roller mills deliver a bright, citrusy flavor.

Tahona mills aren't able to extract as much liquid as roller mills (and are therefore less popular) and require quite a bit of upkeep. Patrón's stone mills last three to four years before needing to be replaced and take two hours to mill a batch of agave. The wheel is made of hand-carved volcanic stone, and the base is river stones. While milling, employees scrape down the sides (like you would a mixing bowl) to make sure the agave is fully milled.

Roller mills last longer than tahona and are easier to fix if a part must be replaced. The process is exactly what it sounds like: cooked agave is sent through a series of rollers to extract as much of the liquid as possible.

Odd man out: diffuser cooking and milling

Some companies choose to expedite the process further by using a diffuser, which can replace both the cooking and milling steps. To do this, raw agave is shredded before being added to the machine. Inside, hot pressurized water is pushed against the plant matter to extract the sugar, creating a sweet juice. This step is repeated several times to achieve the desired sugar level.

The diffuser method is considered highly efficient and extracts more liquid than both tahona and roller milling, meaning distillers can use less agave to create the same amount of tequila. So why would companies choose not to use a diffuser? Those who opt for other methods feel tequila produced using diffusers is less complex than that made by roasting and milling the agave separately. Jamie Salas, head of advocacy, agave at Proximo Spirits (Jose Cuervo's parent company), explained the choice to use diffusers for the brand's Especial tequilas as "critical to meet consumer demand at a price point that is accessible." It's worth noting that Jose Cuervo uses roller milling for other tequilas it produces.

The fermentation process

After the agave is milled, it's time to ferment. Like most steps in the tequila-making process, this can be done a few ways and is impacted by which milling process is used. Tahona-milled agave will include both fibers and the extracted liquid; agave that's been roller milled or diffused will only include liquid in the fermentation step.

Fermentation can be done in either traditional pinewood or stainless steel tanks. Inside the tank, the agave liquid (and possibly solids) is mixed with water and yeast. The exact strain of yeast used is proprietary information and is different from company to company, which is one way to help a tequila stand out from the rest. The solids from tahona-milled agave will naturally rise to the top of the tank and create a cap that traps in aromas. Roller-milled agave — which contains no fibers — does not have a cap, allowing it to develop different flavors.

Stainless steel tanks are generally faster. (Jose Cuervo uses the metal tanks and says it takes, on average, 50 to 60 hours for a batch to be ready to distill; Patrón uses a mix of both, with its pinewood-fermented agave taking at least 72 hours.) They're also easier to clean, and they rarely need to be fully replaced. However, some distillers feel there is less control over this process compared to old-school pinewood, giving more room for error.

Tequila is first distilled into three parts: the head, the heart, the tail

The fermented liquid is next put into stills to be turned into pure tequila. Once distilled down, it's mixed with water to achieve a palatable proof. There are two types of stills used for this step: copper pot and column. Many tequilas use both, as they provide different flavor notes to the spirit.

For copper pot distilling, the fermented mixture is first placed into a larger still. As it heats, the tequila vapors travel up a tube and into a rounded ball (called an ogee) to collect, separating out the solids and other unwanted parts. Then the vapors travel through another tube and are cooled, causing them to turn back into liquid. Each batch of tequila is separated into three parts: the head (which has a very high alcohol content), the heart (what eventually becomes tequila), and the tail (which contains compounds that can be dangerous to consume). After each distillation, the head and tail are mixed and redistilled to make sure as much of the heart concentration as possible has been collected.

After the maximum amount of liquid is distilled into the heart range, it goes through a second distillation in a smaller still. Before the second distillation, the alcohol by volume (ABV) is about 40 proof; the ideal end result is around 110. Then the tequila is filtered and watered down to what you would purchase as a sliver, or blanco, tequila.

Roller mill-produced tequila is generally distilled in a column still, which produces a purer flavor with less agave notes. (Though it can be distilled in copper stills, as is the practice for some Jose Cuervo tequilas.) The process is much the same, but column stills are faster than copper and can process larger batches.

Sustainability is important for tequila producers

Byproducts of the tequila-making process are recycled in a few ways, depending on the brand. They cannot simply be thrown out because the acidity and other variables in the leftover liquids and solids can throw off the balance of the local ecosystem, spoiling the land and water for future generations. For tequila companies, it's very important to take care of the environment, not only because it can impact the ability to grow high-quality agave, but also because (in many cases) their families and workers live in the area.

Some brands, like Patrón, have a water treatment plant and composting facility on the distillery grounds; others hire an outside company to dispose of the byproducts for them. The liquid byproducts are generally strained, cleaned (Patrón uses reverse osmosis), and repurposed. The resulting liquid is not potable but can be used to water gardens, for cleaning, and other similar tasks. The solids are reused in a few ways: Patrón creates compost and then sends the excess to its contracted agave farmers to use. Jose Cuervo uses the solids to make products like straws, surfboards, and other crafts through its sustainability initiative, The Agave Project.

How long each type of tequila is aged for

Once the liquid has completed the final distillation, it's officially silver/blanco tequila. All other varieties are aged in wooden barrels (legally, tequila cannot be aged in any other material), with the type and amount of time it's aged for depending on the desired outcome.

The most common barrel type is American oak, which can be new or previously used to make bourbon. The size of the barrel will depend on the company, with some producers, such as Patrón, relying entirely on smaller barrels. (Picture a beer barrel table in a pub and you get the idea.) Other tequila brands use a mix of smaller and larger barrels, and some only use larger ones. The smaller the barrel, the more flavor it should impart.

Some tequilas — usually the pricier ones — are aged in other types of barrels, such as those previously used to make wine or cognac. This gives a different profile than the American oak, whiskey, or French oak barrels more often used to age the spirit.

When aging, the CRT inspects each barrel, sealing the cork with a special label. If the seal is broken, the tequila goes back to square one, so to speak, and loses its official age. This guarantees the liquor has not been diluted with a younger, cheaper-to-produce spirit. When master distillers want to taste the tequila to check how it's aging, a representative from the CRT will remove the label, watch them take a sample, and then apply a new label. Some larger distilleries have CRT employees on-site daily (rotating every few months to ensure they stay impartial), while others request one as needed.

Things to look for on the label of your tequila bottle

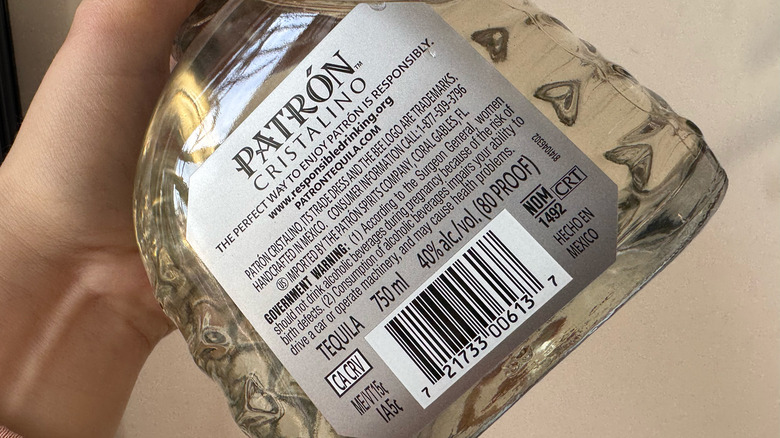

There are a few things to look for on your tequila bottle to make sure you're getting the quality and flavor you're after. First, the type will always be listed (such as blanco, añejo, etc.), as well as if it is a mixto or 100% agave. The label must also tell you if the product has 1% or more additives.

The bottle will have a Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM) number, which is four digits long. This is designated by the CRT to help the regulation group identify where a specific bottle of tequila came from.

Other, more expected, information on your bottle of tequila will be the size, proof, ABV, and its country of origin. (If the spirit wasn't made in Mexico, it is not true tequila.) Some distilleries will include information like the batch number and the person who bottled it if it was done by hand. And, of course, each bottle will have the brand prominently displayed.

How to taste tequila

When trying a tequila for the first time, it's best tasted without ice or any mixers out of a glass that resembles a Champagne flute. David Rodriguez, the head distiller at Patrón, advises you start with the lightest tequila you'll be tasting (often silver/blanco) and work your way toward the darker and more complex varieties. He also suggests you have water and crackers or another bland snack to help clean your palate between each type.

First, hold the glass up to the light to inspect its color and clarity. If you're able, look at it against a white background or piece of paper. Next, tilt the glass slowly back and forth to see the legs of the tequila.

When smelling, put your nose in three places: the bottom, middle, and top of the glass. Each will contain different notes. (If you're in public and not sure you'd like to do all three, stick with the middle.) Keep your mouth open when you inhale, which will allow you to smell more clearly.

To taste, sip the tequila and swirl it around your mouth before swallowing. Then take a breath in through your nose and out of your mouth. This helps you pick up more nuanced flavors and get beyond any spice or burn from the alcohol.

Silver (blanco) tequila tasting notes and food pairings

Referred to as blanco, silver, or plata due to its clear, colorless hue, this tequila is the youngest of all the varieties. It does not have to be aged at all but can be aged for up to 59 days. (60+ makes it a reposado.) The characteristic aromas for this type of tequila are fresh agave, citrus, and herbs, while you can expect to taste a bit of sweetness, that same fresh agave note, and a sharp spice.

Blanco tequila is commonly found in your classic tequila cocktails like margaritas, palomas, and tequila soda. It's also very likely what you'll get if you order a shot of tequila at a bar. Food pairings include seafood dishes like ceviche and fish tacos, as well as fresh snacks such as guacamole or bruschetta.

Reposado tasting notes and food pairings

Aged a minimum of two months, reposado tequila has a light gold or honey hue. The aroma is sweeter than blanco tequila, starting to pick up notes from the barrels it's aged in — like vanilla and honey — but hanging onto those fresh agave scents. Similarly, the taste is starting to take on attributes from the barrel, like wood, bourbon, and spices, but not in an overpowering way. For the tequila-curious who only drank the stuff from a plastic jug in college, picture a mix of silver and gold ... but, you know, good tasting.

Reposado tequila can be used in the same cocktails as blanco for a bolder flavor, or drinks like an old fashioned that generally call for stronger, darker spirits. Reposado is also fantastic in drinks like espresso martinis or spiked coffee. If you'd like to serve food alongside a reposado neat — or a cocktail that features the booze — the best choices would be something with a smoky flavor (think grilled steak or BBQ ribs) or a Mexican classic with a kick like a spicy enchilada.

Añejo tasting notes and food pairings

Moving right down through age and intensity, añejo tequilas must be aged for at least a year. This type of tequila will have a deeper color than reposado and can be described as honey yellow or medium gold. When smelling, you should be able to detect notes of honey, prunes, and raisins. (If you don't, it may have caramel color added to make it appear better aged than it is.) Añejo tequila has many dessert-like flavors: cinnamon, caramel, vanilla, and cooked agave.

If you'd like to try añejo tequila in a cocktail, opt for something like an old fashioned, a Manhattan, a winter punch, or a hot beverage such as a spiked cider or a toddy. (If drinking tequila makes you warm enough already, both of these bevvys can be iced.) Food with booze is always a good call, and if you're sipping añejo tequila, I recommend dessert to match up with those sweet notes, like chocolate cake, flan, or bananas foster.

Extra añejo tasting notes and food pairings

As the name implies, extra añejo is aged longer than añejo tequila, for a minimum of three years. The color is deeper, with an amber-honey hue. The aromas are strong — oak, prune, and brown sugar — and the flavors you will taste are oak and spices.

Cocktails don't often feature extra añejo tequila, but if you'd like to try the variety in a drink vs. sipping it straight, consider dark spirit classics like an old fashioned, a Manhattan, a julep, or a boulevardier. For food pairings, stick to the same desserts you'd serve with añejo tequila, or even just a piece of high-quality dark chocolate.

Cristalino tasting notes and food pairings

Though you may think cristalino is a type of blanco tequila due to its color, this is actually considered an añejo. The drink is made by mixing blanco and añejo together and then filtering it with charcoal to remove impurities and achieve that crystal-clear look. While the color is all blanco, the aroma is more similar to an añejo but softer and lighter. The taste is smooth and bright, with notes of cinnamon and caramel.

As it's generally more expensive than other tequilas, I wouldn't suggest mixing cristalino. That said, if you want the flavors of añejo tequila but with less bite or color, try cristalino in a simple drink like a tequila soda, margarita, or paloma. If you'd like to enjoy a meal with your glass of cristalino, foods like baked salmon, grilled chicken, and panna cotta all go well with this variety.

Other varieties of tequila

Some tequilas fall into the categories above but are aged in different types of barrels or treated in a unique way that impacts the finished products. In general, these tequilas will be made in smaller amounts and/or command higher prices.

One example of this is Patrón's El Cielo ($129.99 at Total Wine & More), a silver tequila that's been distilled four times. This results in a softer, less intense sip than the brand's standard silver tequila, which costs just $42.09 and includes 50 more milliliters of booze.

Another is its Burdeos, which is made by aging the brand's añejo tequila for an additional year in new French oak barrels, followed by six to nine months in a Bordeaux wine barrel. The ultra-aged tequila takes on the flavors of the wine, like cherry and dried fruits, in addition to developing more of those oaky, spiced notes you expect from an añejo. A 750-milliliter bottle of Patrón's Burdeos costs $419.99; the same-size bottle of Patrón's extra añejo is $79.99.

Created similarly to how Patrón creates its Burdeos is Jose Cuervo's Reserva de la Familia Añejo Cristalino Organico. This tequila is finished in Pedro Ximenez sherry casks, which impart stone fruit notes to the liquor. Retailing for $164.99 at Total Wine & More, this cristalino is nearly five times as expensive as Cuervo's Tradicional cristalino ($34.99).

Identifying additives in tequila

There are four additives that are used in the tequila-making process: glycerin, caramel coloring, oak extract, and jarabe. Each helps the tequila maker achieve a different desired outcome. Tequila cannot be 1% or more additives; if a distiller exceeds that percentage, the product is no longer considered a pure tequila and must list on the label that it includes additives. This is different from a mixto tequila, which is not made entirely from agave; tequila can contain additives and still be 100% agave tequila.

A natural result of the tahona-milling process, glycerin adds viscosity to the spirit. Both natural and added glycerin result in the tequila having legs in the glass and add weight and body. Glycerin added after the distillation process tends to disappear in the middle of your sip, leaving you without the full mouthfeel when compared to similar tequilas that have naturally occurring glycerin.

Tasteless and odorless, caramel coloring helps brands deliver a uniform tequila color from batch to batch. It can also be used to make the alcohol seem like it's been aged for longer or in smaller batches, or to hide that a tequila has been aged in barrels a bit past their prime. (Some companies will sell used barrels to smaller producers or cheaper brands; others like Patrón repurpose them into furniture or arts and crafts or allow workers to take them home.) It's difficult to tell if a brand is using caramel coloring in its tequila, but if you notice the hue is much darker than other tequilas of the same type, it's very possible this has been added.

Oak extract mimics the smell and taste imparted by wood barrels during the aging process. Similar to caramel coloring, this is used to make tequilas seem like they have been aged for longer or to fix tequilas that have been aged in older barrels. This additive can also be difficult to identify, but it often comes with an overly strong oak scent or flavor.

A flavoring agent, jarabe can be made from various ingredients like sugarcane, corn syrup, stevia, and even agave. It imparts agave-like notes and sweetness to tequila, helping to mask harsher flavors. This one is also tricky to pin down, but, again, if the liquor tastes sweeter or more dessert-like than you would expect, it may contain jarabe.

A small number of producers, like Patrón, proudly share they are additive-free. While not advertising additive-free status does not mean additives are used, companies that do include additives generally dance around the subject, refusing to outright state if they use additives. If a brand is being vague, there are probably additives in its tequila.

Go forth and impress with your newfound tequila knowledge

While a trip to Mexico might not be in the cards — or budget — for every tequila or tequila-curious drinker, it's important to know what to ask for, look for, and how to treat the spirit to have the most enjoyable experience. That way, when you're in the store or at the bar perusing your options, you won't end up spending way more than you need to get where you want to go. (Of course, if you want to salt-shoot-lime your way through a $200 bottle of extra añejo or blend up a frozen margarita with a triple-distilled blanco, that's your choice. Who are we to judge?)

And while I probably won't start going to tequila bars and ordering glasses of the stuff straight, I now know what to do with those gorgeous bottles that have been sitting around my kitchen collecting dust. I also have a larger appreciation for the craft after seeing how the spirit is made: from jimadors and farmers dedicating a decade-plus of their lives to the agave, to the distillers fermenting and aging the tequila, always searching for the perfect balance. I even admire the people who bottle the booze after watching the team at Patrón chatting and listening to music while still making sure each tequila looked exactly right. (What, you thought a machine labeled, wrapped in tissue paper, and boxed up each bottle?)

Armed with the knowledge of how to read a tequila bottle label; what to expect from each variety, the foods to serve it with, and cocktails to mix it into; tips to spot an inferior pour masquerading as a higher-end offering; and more, I hope you can now feel confident in any and all tequila drinking situations. Arriba, abajo, al centro, pa' dentro. ¡Salud!