11 Little-Known Ways Prohibition Hurt The US

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Prohibition was a fascinating time in American history, and the effects of the 18th Amendment are still being felt today. Before we get into that, though, here's a little background. Prohibition was enacted in 1920 and repealed in 1933. Between those years, the manufacture and sale of alcohol were illegal, and the whole thing was largely the work of groups like the Anti-Saloon League and the Women's Christian Temperance Union, which grew out of the Protestant church.

The theory behind Prohibition was that all (or at least most) of the evils that befell humankind could be traced back to alcohol. Get rid of the alcohol, the thinking went, and people would be happier and healthier, and behaviors of domestic violence and crime would disappear. Did it work? Absolutely not. It turns out that people did not appreciate being told they couldn't have a drink, and the fallout was swift, immediately and permanently changing the country in a surprising number of ways.

There's a lot that's been written about the result of Prohibition, like the rise of organized crime built on the shoulders of bootleggers and rum runners. We've all heard about how Prohibition gave rise to people like Al Capone, but that's just scraping the surface. Some things that came out of the movement are arguably good — finger foods ruled the speakeasy scene, and we can't complain. But, there are plenty of less well-known ways that Prohibition did some serious damage to America's culture, food scene, and people.

Many of the country's wineries were nearly completely destroyed

Wine lovers know that there are a few hot spots when it comes to the best wineries. Napa Valley wineries, in particular, are often at the top of bucket lists, and some might be familiar with the wine that comes from New York's Finger Lakes. But did you know that Illinois was making some of the country's best wines pre-Prohibition?

That was in large part thanks to the state's large population of German immigrants, but their wineries — along with those in other Midwestern states like Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio — were decimated by Prohibition. Missouri, for example, was once home to the second largest winery — Stone Hill — in the country, but Stone Hill was forced to switch to producing mushrooms when Prohibition hit.

That's not the only area hard-hit. Most of New Jersey's wineries went out of business, with one surviving thanks to a license to produce wine for religious and medicinal use. Similar fates struck the wine producers from North Carolina down into Alabama, Arkansas, and even Texas. Decades-old vineyards and wineries needed to find another way to survive or leverage connections with religious organizations to make sacramental wine. If not, they went out of business. Many were forced to do the latter, and wine production in the U.S. shifted drastically.

California vineyards were replanted with new varieties terrible for wine

California has been a center of U.S. wine-making for a long time, going back to the mid-1700s. Fast forward to Prohibition, and things changed in a big way when wineries and vineyards needed to find a new way to make ends meet. In many cases, these places survived by shifting their business model to sell fruit juices and the grapes themselves, which people could then use to make their own wine. That seems straightforward enough, but there was a massive problem.

With this new way of doing things, grapes needed to be able to survive shipping, and it was no short trip. Two of the biggest markets for California-grown grapes were New York and Chicago, and unfortunately, many of the best grapes for wine-making weren't hardy enough for the rigors of transportation.

Countless vineyards — long-perfect for wine-making — were ripped up and replanted with tougher varieties. These newly planted grape varieties included those with higher yields, thicker skins, darker shades, and more tannins, which basically allowed people to make their own barrels of really bad wine. Destroying and planting vineyards isn't a single-season process, either: It takes around three years before a new vineyard is productive, and for really top-end wine, that's about 10 years of growth. Even after the repeal of Prohibition, going back wasn't an overnight process.

Bad homemade wine led to people turning their backs on the industry

Sure, the U.S. is getting some serious recognition in the wine industry, but it's still a young'un as far as the world stage is concerned. The world's oldest operating winery is over 1,000 years old, and France has been making wine for around 2,600 years. For the U.S., early attempts — which ended largely in failure — go back to the 1600s, and even though enterprising wine-makers kept at it, Prohibition was enough to derail the whole thing.

Many Americans were reduced to trying to make their own bad wine from less-than-perfect grape varieties, and then turn it into something drinkable with the addition of sugar. In the years around Prohibition, a lot of people were doing it — so many that the amount of wine people were drinking actually skyrocketed. Unfortunately, that meant that many people got used to associating wine with barely drinkable, highly alcoholic products that had no redeeming factors whatsoever.

What followed Prohibition was catastrophic for the wine industry. Simply put, people who now had access to other kinds of professionally produced beer and liquor wanted nothing more to do with the wine that had seen them through the years of Prohibition. The bottom fell out of the wine industry, and wineries had to start from scratch to remind people that what they had been making in their basements wasn't all that wine could be.

Entire apple orchards were destroyed

The old saying goes that there's nothing quite as American as apple pie, but the history of apples in the U.S. isn't quite as straightforward as it might seem. Johnny Appleseed was based on a real person named John Chapman, who really did plant a lot of apple trees. Settlers who were promised land in exchange for turning that land into viable orchards hired him to do a lot of the hard work of planting trees, but the trees he tended to plant yielded apples you wouldn't want to eat.

Instead, they were perfect for making cider. Hard cider was incredibly common for decades, but we're talking about Prohibition. In "Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story," author Howard Means says that many of these orchards were destroyed during Prohibition to stop people from making their own hard cider.

Fast forward to the 2010s, and cider was once again becoming popular in the U.S. There was a massive problem, though. Cider production requires specific varieties of apples that have specific amounts of things like sugars and tannins, and those apples just weren't being grown in the U.S. anymore — and hadn't been since Prohibition. Many varieties disappeared almost completely, and the market shifted toward eating apples instead. Newly planted orchards take years to mature, and as cider-making apples are viewed as not as profitable as eating apples, the cider industry continued to struggle to source ingredients.

One particular concoction is estimated to have paralyzed thousands of people

There's a long history of drinks like the Pimm's Cup being used as a health tonic, and during Prohibition, some wineries and distilleries survived by getting permission to make medical alcohol. It was a huge business, but unfortunately, it had a devastating impact on some of the people who drank it — particularly the so-called medicinal liquor that was made by bootleggers.

Jamaica Ginger — or Ginger Jake — was a popular medicinal tonic at the time, and in 1928, gallons of bootlegger-made Ginger Jake were sold across the country. Unfortunately for those who drank it, it contained a chemical that caused nerve paralysis in the large muscles of the body. It's not clear just how many people were impacted by the tonic, but most estimates suggest somewhere around 50,000 to 100,000 people were permanently paralyzed.

The story doesn't have a happy ending, and in the 1970s, researchers were still studying the long-term paralysis and other problems associated with the poisoning. Effects of the illness were easily identifiable, and after Prohibition, many of those who displayed symptoms found themselves shunned, ridiculed, and blamed for their fate. "Jake walk" and "Jake leg" — because those affected were often seen limping — became topics for protest and blues songs, and it's also with noting that of the two bootleggers who had made the triorthocresyl phosphate-laced tonic, only one was sentenced to jail time amounting to two years.

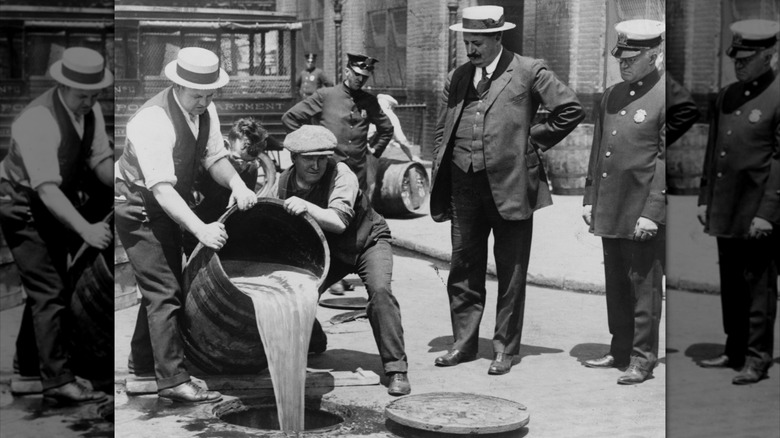

Poisoned alcohol — courtesy of the U.S. government — killed thousands

During Prohibition, people had to get creative to source their alcohol. In addition to liquor made at home, supplied by bootleggers, or created for medicinal usage, people also got their hands on legitimately manufactured industrial alcohol. That's not just used as cleaners, but it's crucial to industries from textiles to cosmetics.

It's well-known that the government and law enforcement waged war on those trying to skirt Prohibition, and somewhere along the line, someone came up with a plan that would turn deadly. The idea was to add chemicals to industrial alcohol that would make anyone who drank it incredibly sick, but it did more than that. It's estimated that as many as 10,000 people were killed by alcohol purposely poisoned by the government.

People knew about it at the time, too: Will Rogers was quoted (via CATO) as saying, "Governments used to murder by the bullet only. Now, it's by the quart." The stories are awful and include dozens who fell ill or died celebrating Christmas in New York City in 1926. When the government began adding non-lethal chemicals to industrial alcohol in the mid-1920s, bootleggers got better at removing the chemicals, so the government responded by simply adding deadlier concoctions that included things like kerosene, acetone, and carbolic acid. There's really no way of telling how many were permanently hurt or killed.

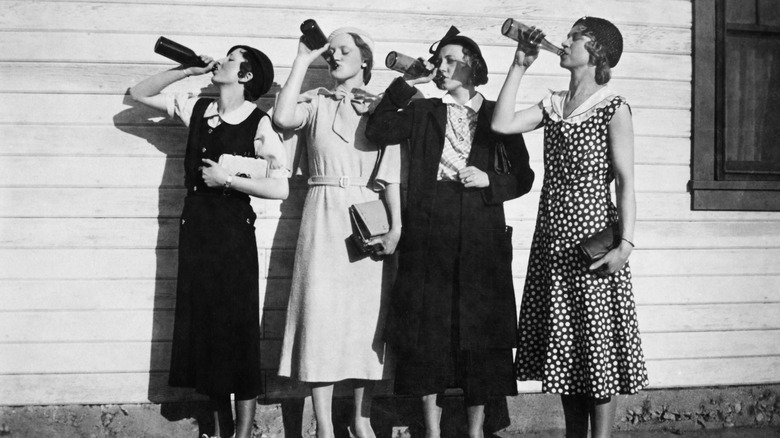

Prohibition made drinking more common and more dangerous

It's kind of Psychology 101: If you tell someone not to do something, what's the first thing they're going to do? That thing. That's what happened with Prohibition, and instead of making alcohol use go away, statistics — including those gathered from insurance companies — suggested cases of alcoholism rose by around 300%.

There were a few things at work here, starting with the idea that suddenly, drinking wasn't just a matter of grabbing a drink after work — it was an act of rebellion. Going to speakeasies was exciting, and being a part of that counterculture that grew up around them was pretty darn cool. And while the kind of saloons and bars that the Temperance Movement had targeted did close, a lot of speakeasies were born. Some of the nation's biggest cities had 10s of thousands of these secretive bars, and it's been argued that it was actually easier to get a drink.

Without government oversight regulating what went into alcohol, it also became much more dangerous. Demand for medicinal alcohol skyrocketed, and so did the use of drugs and tobacco. Not only that but there was a good chance you were getting alcohol that was ridiculously strong. Today, a cask-strength bourbon might be between 60 and 75% ABV, but during Prohibition, alcoholic beverages contained a much higher ABV than pre-and-post-Prohibition.

Businesses other than bars found themselves closing instead of thriving

When we think of bleak periods in U.S. history, it's probably the Great Depression that comes to mind first. But the Prohibition era was pretty bleak, too. One of the things that prohibitionists pushed was the idea that if people weren't buying liquor, they'd spend that money on other, better products, businesses, and long-term investments. Since we're talking about it, you might guess that's absolutely not what happened.

It makes sense that bars went out of business, but they weren't alone. The restaurant industry was devastated, no longer able to sell alcohol with dinner. Many closed, along with other businesses, like dance halls and nightclubs, that had been profitable due to liquor sales. Theaters had expected throngs of people seeking entertainment, but that didn't happen, either.

And yes, distilleries and wineries closed, but that had a ripple effect that cascaded through the American economy. At the time Prohibition kicked in, alcohol and liquor were the country's fifth largest industry. Not only were around 170,000 liquor stores suddenly out of business, but it went in the other direction, too. Barley farmers needed to find new income, and coopers were no longer needed. An estimated 250,000 people lost their jobs.

Prohibition revitalized the KKK

Prohibition is almost surprisingly complicated, and in one way, it wasn't about alcohol at all. Alcohol and alcohol use was one way that temperance groups could promote racist and anti-immigrant agendas because, in a nutshell, saloons had become gathering places for the working class, and particularly, immigrants searching for a community in their new home. Saloons were also places to discuss politics and votes, and there's some tenuous connections that were made here between alcoholism, the poor, the working class, and America's immigrant influx. When the Anti-Saloon League was formed, they very quickly threw in with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

Listen to the rhetoric of prohibitionists, and you'll find that they very vehemently pointed to Catholic immigrants as being responsible for pretty much all of society's ills. This fell in line with the KKK's mainline beliefs and put the KKK in a position where they could kill, burn, pillage, and raid their way across the country in the name of enforcing the 18th Amendment.

Along with immigrant groups and families, Black business owners were also specifically targeted, even as the KKK touted the belief that these were the group most likely to be breaking Prohibition statutes. In some cases, the government's official Prohibition Bureau agents tapped members of the Klan when they needed backup.

Major and violent crimes skyrocketed

Prohibition was ushered in by a lot of people making a lot of promises, including baseball player-turned-evangelist preacher Billy Sunday. He promised (via CATO), "The reign of tears is over. The slums will soon be a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent."

In the years leading up to Prohibition, crime rates had been dropping. Hindsight is 20/20, the saying goes, and we know today that crime skyrocketed almost immediately — but we're not just talking about organized crime. Yes, Prohibition made it possible for the mob to step up, but they weren't the only problem. Over the course of a decade, the nationwide murder rate increased by 78%, and if you look at just the first year Prohibition was active, crime overall was up 24%. That included drunk driving, burglary, and assault, and as far as the impact on prisons, let's take Sing Sing Prison as an example.

In 1919, there were about 1,100 inmates. That rose to 1,500 with the start of Prohibition, and by 1922, that was up to 1,600. By 1932, the number of people being held in federal prisons had risen 366%, and along with that came all the problems of an overloaded system ill-equipped to deal with severe overcrowding. When Prohibition was repealed, violent crime — almost across the board — dropped.

Making alcohol illegal made getting treatment for addiction impossible

Today, there are all kinds of options for anyone looking to get help with addictions of all kinds, and even bars are becoming more mindful of abstaining from alcohol. Many bars are even embracing Dry January with booze-free offerings, but Prohibition had a devastating impact on those seeking help for addiction.

Some of the driving factors behind Prohibition included claims that alcoholism was a moral failure, and in some cases, it was likened to things like criminal activity and abuse. That's a wildly outdated view of addiction, but throughout the 1920s, those dealing with addiction issues became villainized. For many, access to support and treatment simply wasn't there. Alcoholics Anonymous is still perhaps the most well-known support group, and it was only founded post-Prohibition.

During Prohibition, many support and treatment groups were focused on therapies that involved religion, and one of those groups — the Oxford Group — helped lay the groundwork for Bill Wilson's Alcoholics Anonymous. It's impossible to tell just how far Prohibition set addiction treatments back, but it's worth noting that when Wilson went through what was then standard procedure, it was a doctor-prescribed routine of belladonna (which caused severe hallucinations) and other barbiturates that oftentimes didn't work.