Ming River Sichuan Baijiu: The Ultimate Bottle Guide

This summer, I spent a month in China, where my instincts as a tequila professional led me in search of the local spirits selection. I expected to find the usual suspects (whisky, vodka, tequila... maybe some rum) but one drink appeared everywhere, poured into tiny clear stemmed glasses at nearly every meal: baijiu (白酒, pronounced "bye-jo"), China's ubiquitous national spirit. I realized, to my horror, that I had never actually tasted baijiu. That changed quickly as I found myself "ganbei-ing" through countless rounds at family dinners. It was an acquired taste but paired with food, it became very enjoyable. Upon returning, I searched for baijiu at my local digs but was met with blank stares. It dawned on me that a spirit so deeply woven into Chinese culture was virtually nonexistent here.

This is a familiar narrative for many who have traveled to China and one the founders of Ming River Baijiu decided to change. What sets Ming River apart isn't just its distinct flavor or production process; it's the unique challenge of selling a spirit most drinkers outside of China have never encountered. Unlike brands like Pendleton Whisky or Benchmark Bourbon, which can rely on consumers' familiarity with it's categories, Ming River must first introduce drinkers to baijiu as a spirit. It's not just selling bottles; it's about educating an entire market on a new beverage altogether. Recently, I reached out to Matthias Heger, cofounder of Ming River, to learn more about the brand.

A History of Baijiu

To truly appreciate what sets Ming River apart, it's essential to first understand the history of baijiu and the intricate craft behind its production. As one of the world's oldest alcoholic beverages, there are records of liquor (in general) being consumed in China since 7000 to 5000 BC. It was originally brewed from rice, honey, grape and hawthorn fruit. People believed that drinking alcohol could transcend reality into a spiritual realm where they could reconnect with their dead ancestors. Because of this property, emperors began maintaining court brewers and liquor was used as a method to connect people not only to spirits but also to each other. It was a tool to build friendships and allies. With influence from chemists in the middle east in the 13th century, fermented liquor started to be distilled through stills which strengthen the alcohol content. During the Ming dynasty, this distilling process was refined even more and different distinct styles of alcohol began to emerge such as shaoxing, baijiu and mijiu (mostly used as a cooking wine). With the creation of the People's Republic of China, government-run distilleries were being set up to produce the spirit we know as baijiu today. The four main baijiu distilleries created were: Kweichow Moutai, Luzhou Laojiao (remember this name!), Wuliangye and Yanghe.

Traditional Baijiu Production

Baijiu is made from a variety of fermented grains such as barley, rice, sorghum and wheat. While whisky is generally cooked, mashed, fermented and then distilled (in that order), baijiu has a different production process which draws out different flavors. First, the grains are steamed to prepare them for fermentation. Qu (pronounced "choo"), a mixture of yeast, mold, grain and other microorganisms developed through open-air fermentation, is then added to the grains in solid form. This converts starches to sugars and sugars to alcohol in one step as opposed to malting grains to make sugars and then fermenting that separately as a liquid. This is commonly done in a stone pit or mud pit.

The process of using qu in alcohol production created more potent drinks as opposed to wine and ales. Fermented grains are then loaded into a still where the alcohol is vaporized and collected. Distillation occurs at least twice: once to remove the tail esters and again to remove the heads. The amount of heads and tails left after distillation contribute to the flavor of the spirit. All bajiu is aged for a minimum of one month in clay pots to oxidize and mellow out the harsh edges. Baijiu distillates are generally blended and diluted after aging to create the desired flavor profile.

What makes Ming River's production process unique?

Ming River is crafted at Luzhou Laojiao, one of China's oldest distilleries. Its primary ingredient is sorghum, a drought-resistant grain that thrives in tough conditions. Unlike other grains, sorghum's deep red kernels are packed with starch and calcium, which when fermented, develop a distinctive fruity sweetness — a hallmark of Ming River's strong-aroma baijiu. This is in contrast to baijiu produced from rice which are more citrusy and delicate.

The mashed sorghum begins its transition to baijiu through solid-state fermentation in underground stone pits that have been continuously used over the distillery's 400 year history. "1,000-year pit, 10,000-year mash" technique is a fermentation process bepoke to Ming River's distillery. These ancient pits house a rich microbial ecosystem that plays a crucial role in developing the deep fruit and umami notes that define Ming River's signature flavors. Ming River's fermentation process is driven by Luzhou Laojiao's proprietary qu which contains a mix of yeasts, molds, and bacteria.

After fermenting for two-months, the mash is then transferred onto steamers (which resemble giant dim-sum baskets) and distilled in traditional Chinese pot stills. After distillation, the spirit is aged and meticulously blended, resulting in Ming River's bold, layered profile — a testament to centuries of craftsmanship. It is then bottled at a 45% ABV with water from local wells.

The formation of Ming River Baijiu

In the early 2000s, German exchange student Matthias Heger was studying in China when he noticed something intriguing: baijiu was everywhere, yet there seemed to be many hidden rules around how to consume the beverage that were not universally explained to foreigners. This left him feeling apprehensions about consuming baijiu in a formal setting as the fear of making an etiquette mistake was a real factor, however, he remained curious about this topic. This fascination eventually led him to attending a 2014 lecture in Beijing by Chinese historian and leading authority on baijiu, Derek Sandhaus. When he learned the meaning behind each custom, consuming baijiu became more approachable.

The more Heger learned about baijiu, the more he came to appreciate its complexity and diversity — akin to whisky or mezcal, yet deeply rooted in its own rich history and tradition. Determined to introduce baijiu to a global audience, Heger and his friends cofounded Capital Spirits, a pioneering Beijing baijiu bar that experimented with serving the spirit in flights and cocktails. This hands-on experience gave him unique insight into how international drinkers engaged with baijiu and what flavors resonated with them. In 2018, Sandhaus, Heger and their friend, Bill Isler, took the next step: creating their own brand, Ming River Baijiu. It's mission was to bring China's iconic spirit to the rest of the world.

Where does the Ming River name come from?

Matthias Heger explains that the name "Ming River" comes from a combination of "Ming" from the Ming Dynasty when the distillery, Luzhou Laojiao, was actually founded and "River" which symbolizes the Yangtze River, which runs through Luzhou, where the baijiu is made. "We wanted a name that reflects heritage and movement," Heger recently told Tasting Table. This name also represents the brand mission: bringing baijiu to new markets, just as rivers connect different cultures and places.

Historically, the term "bajiu" was a catchall used to refer to any clear liquor, in modern day, it exclusively refers to Chinese distilled spirits (not to be confused with liquor). As of 2019, baijiu accounted for a staggering 54% of the total brand value of the alcoholic beverage market. At the pinnacle of this category sits Kweichow Maotai, a top-tier baijiu brand renowned for its prestige. A 500ml bottle of this soy-aroma baijiu can easily retail for over $1,000 USD. Yet despite its dominance in the Chinese market, baijiu still remains rare on Western backbars. For brands like Ming River Baijiu, this lack of visibility poses as the greatest hurdle in garnering international attention.

What does Ming River Baijiu taste like?

Baijiu styles vary dramatically from region to region, shaped by local palates and culinary traditions. In the south, where sweet and savory flavors dominate, light aroma and rice aroma baijius are commonly distilled, offering a softer, more delicate profile. In the north, where bold, spicy, and intensely savory dishes take center stage, strong aroma and sauce aroma baijius provide a robust pairing to this cuisine.

There are generally four main types of baijiu, with strong aroma baijiu dominating 70% of bottles sold. Beyond these flavors, lesser-known varieties such as medicinal aroma, sesame aroma, bean aroma, and phoenix aroma add even more nuance to China's vast and intricate baijiu landscape.

Ming River Baijiu is distilled in Sichuan province which is located in central China. Besides being the home of China's national animal (the panda), Sichuan is known for their bold spicy flavours, especially mala, which is a numbing spice made from blending hot peppers with peppercorns. Alcohol consumed with this type of food is equally as bold.

On the nose, Ming River produces a green apple scent that gives way to a symphony of tropical fruits including papaya, guava, and melon, rounded out by a hint of ripe cheese. It tastes of spicy pink peppercorn with pineapple and anise. The finish is long, mellow, with a slightly earthy umami note. According to cofounder Matthias Heger, it enhances spicy, umami-rich dishes like Sichuan hot pot or roasted duck.

The traditional way to drink Ming River

There are many ways to consume baijiu. When drinking baijiu the traditional way, there are certain unspoken rules rooted in China's ganbei culture that are expected to be followed. Unlike Scotch or cognac that are slowly savored, baijiu is rarely sipped. Instead, it is downed in a communal toast, with a hearty "Ganbei!" (a Chinese toast which literally means "dry cup") When toasting, everyone should finish their glass in one go. Refusing or hesitating can be seen as impolite, as clearing your cup is a gesture of camaraderie and respect.

The order of toasting also matters. The highest-ranking or eldest person at the table typically initiates, and as a sign of deference, it is customary to position your glass slightly lower than theirs when clinking. And perhaps most importantly, baijiu is never meant to be consumed alone – it is a social drink, always accompanied by food and shared in good company. So, for those looking to pregame with baijiu, consider reaching for vodka instead.

In America, Ming River Baijiu is introducing drinkers to baijiu through cocktails, making the traditionally fiery spirit more approachable. Yet, even in cocktail bars, elements of ganbei culture is finding its way into the experience, transforming baijiu from just another ingredient into an experience.

How to use Ming River in cocktails

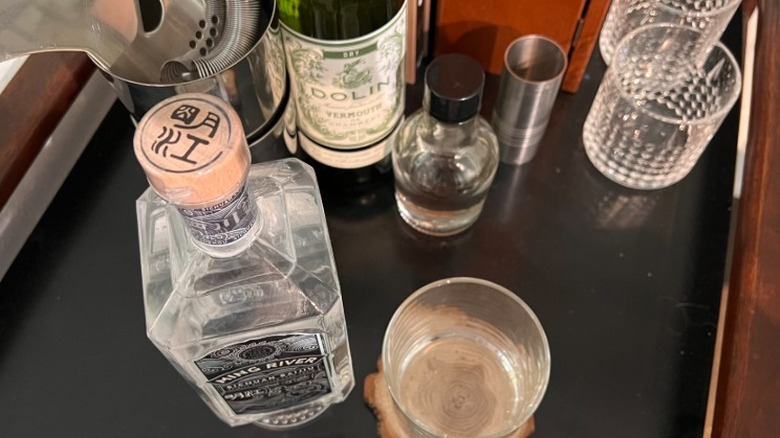

Ming River can be enjoyed in two ways: the traditional method – served neat at room temperature in delicate clear stemmed glasses or as the star ingredient in an innovative baijiu cocktail. The bold, complex profile of strong-aroma baijiu pairs effortlessly with a surprising range of flavors, from Chartreuse and guava to lime juice, passionfruit, and peppercorn-infused syrups. One standout creation for bars is the Dance Monkey Milk Punch, a cocktail that blends Ming River with banana syrup, soy milk, pandan leaves, jasmine tea, and lemon juice for a fragrant, silky-smooth experience.

Matthias Heger recommends the Paper Crane which was originally served at Capital Spirits. It balances baijiu's fruitiness with citrus and amari, making it a great introduction for newcomers. Heger elaborates that baijiu's flavors are so unique that bartenders are constantly experimenting and coming up with new and unique cocktail ideas (which is highly encouraged!)

Other ways people have been enjoying baijiu is in ice cream or in their Luckin' Coffee latte which has become so popular in China they can't make it fast enough!

Ming River Baijiu in the wild

Ming River is at the forefront of brands leading the charge to introduce baijiu to western palates. As bartenders are typically the earliest adopters of new trends, you'll most likely find it in America behind a cocktail bar. While the spirit's bold and complex flavors can be an acquired taste, integrating it into cocktails is a great way to highlight it's sweet, umami profile.

Mixologists have been experimenting with baijiu's layered flavors, creating balanced and intriguing drinks that bridge Eastern and Western traditions. At Paper Plane in San Jose, the Khaosan Spritz cocktail brings out the spirit's lush aromatics by pairing it with complementary ingredients like vermouth, chrysanthemum, grapefruit bitters, and cucumber bitters. Meanwhile, at Ye's Apothecary (in New York), the Red Sorghum cocktail blends Ming River with aperol and pineapple, resulting in a bright, bittersweet concoction that tempers baijiu's signature funk with juicy citrus notes.

For those eager to explore Ming River baijiu outside of a bar, specialty liquor stores and online retailers stock bottles for home experimentation. Expect to pay $35 to $45 per 750ml bottle which makes it a mid-range option. Some premium baijius, particularly those from renowned brands like Moutai or even the house brand of Ming River's distillery, Luzhou Laojiao, can fetch hundreds of dollars per bottle. Mass-market varieties (such as Jiangxiaobai) falls in the $20–$30 range. Ming River strikes a balance, offering a quality introduction to Sichuan-style baijiu without the sticker shock of luxury labels.

Ming River Baijiu started with a Beijing baijiu bar called Capital Spirits

The origin of Ming River Baijiu can be traced to an unassuming bar built in a 100-year-old building in a quiet alleyway. In this tiny hutong, Capital Spirits emerged as the world's first bar dedicated entirely to baijiu. From the start, people were skeptical. Cynics told Matthias Heger and Bill Isler that a bar focused entirely on baijiu was doomed to fail. This did not deter him from opening the bar. Matthias and his team saw potential where others saw risk. They approached baijiu not as a formal banquet drink but as a spirit worth savoring, understanding and comparing.

Through curated tasting flights and guided sessions, they introduced guests to the different styles of baijiu, from the floral elegance of light aroma to the bold, fermented complexity of sauce aroma. Many visitors arrived with hesitation but left as converts, proving that with the right introduction, the world was ready for a high-quality, approachable baijiu brand. Within a year, Capital Spirits had built a loyal customer base and garnered international media attention for redefining baijiu's image to foreigners and expats. Though the bar has since closed, its legacy endures. Through Ming River Baijiu, Heger and Isler's passion and enthusiasm have been channeled into bringing baijiu to new audiences around the world.

Education is one of Ming River's brand pillars

When Matthias Heger and Derek Sandhaus first encountered baijiu, they didn't immediately embrace it. Without an understanding of ganbei culture, the spirit's communal drinking traditions felt unfamiliar and confusing. As they each took the time to explore baijiu's production and historical significance, their perspectives shifted. They came to appreciate baijiu not just as a drink, but as a reflection of China's centuries-old drinking culture. This journey is why education remains at the heart of Ming River Baijiu. Sandhaus has authored several books on baijiu including "Baijiu: The Essential Guide to Chinese Spirits" and "Drunk in China: Baijiu and the World's Oldest Drinking Culture."

For those eager to venture deeper, Ming River Baijiu University offers a free educational platform with interactive video, detailed readings and quizzes to reinforce baijiu education. Intrigued by the idea of demystifying baijiu (and being $0 didn't hurt), I enrolled in these myself. The coursework spans an impressive range, covering everything from the origins of liquor in ancient China to the meticulous fermentation and production process that gives each style its signature complexity.

Students also learn about Chinese drinking etiquette which is vital for anyone trying to navigate social events in China. Those who complete a course earn a certificate recognizing their growing expertise in baijiu. Whether you are a spirits professional looking to add to your repertoire or a curious drinker, these courses offers a rare opportunity to engage with one of the world's oldest and most misunderstood spirits.