Red Hot Sorbet Recipe With Bill Smith Of Crook's Corner In Chapel

Crook's Corner chef Bill Smith talks about what's heating up Southern food

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When Bill Smith took up his post as head chef of Chapel Hill, North Carolina's Crook's Corner in 1993, everyone complained that the collard greens were too hot. "Now, nobody ever says that. And they're not any different. It's the same recipe," he laughs.

This might seem like a minor detail, a culinary trend wafting through the foodosphere, but to Smith, it's proof positive of a shift in a culture—and its food—that hasn't always been quick to embrace many flavors of change.

The 66-year-old James Beard-nominated chef and author is prone to warm laughs, deep insights and homespun truths, and he's come to think of the attitudinal evolution in terms of what he calls the "potato salad divide."

Smith believes you can tell a lot about how people lead their life by how willing they are to consider other people's takes on the classic side dish. One group of people thinks there's only one kind of potato salad, and that's the kind Grandmama made. Another thinks that her recipe is good, but they're eager to try other kinds and expand their horizons.

"The people on the grandmother's side are scared of everything," Smith says. "The people on the other side understand the deliciousness of the unknown. Everything they do, you can judge by that."

And it has a profound effect on the way people eat. When Smith was growing up in Eastern North Carolina, his family would gather around his grandmother's table for a big, seasonally driven lunch every day. Though he's eaten all around the world, he cites the women in his family as the best cooks he can name to this day. He credits them with instilling a deep love of dining in him and giving him a foundation for his three-decade career as a chef. But if he dares to mess with their recipes, he knows he'll hear all about it.

Case in point: A couple of years back, Smith made a twist on a classic Atlantic beach pie recipe—a lemon pie that was served at restaurants along the coast while he was growing up—at a Southern Foodways Alliance outing. It was a smash hit, and when he put it on the restaurant menu, it captured a lot of media attention—and some serious critique from longtime lovers of the pie who couldn't get over the fact that he used whipped cream rather than making a meringue using the leftover whites from the yolks used in the filling.

"A) I broke with tradition, and b) I wasted those egg whites," Smith admits. "And if you grew up with people who were raised in the Depression, they never got over it, ever, ever, ever, ever. It's a cuisine that came out of poverty. You had to make do with not very much, so maybe it took extra effort to be good. It is a thoughtful cuisine."

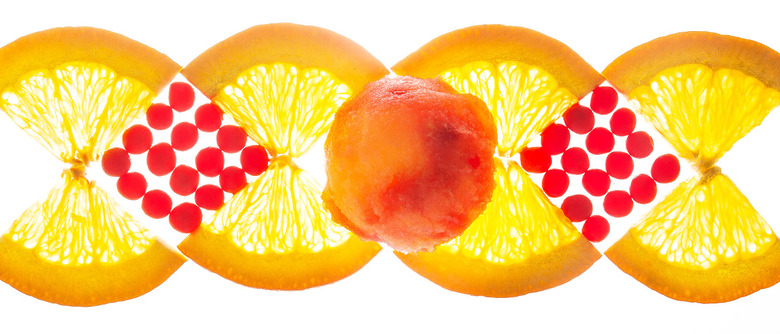

It was with them in mind—and the tight margins of running a restaurant—that Smith devised the Orange Red Hot Sorbet (see the recipe) he serves at Crook's Corner. "I call this 'clown food,'" he jokes, "because it sounds really dumb, but it's really good. It's a sorbet made out of orange juice and Red Hots. We make fresh juice at our bar every night, and it's only good for a day or two. Very often, there's stuff left over. You have to figure out ways in restaurants to use everything."

And also in keeping with Southern traditions, it's oddly seasonal. "You can't just go and get Red Hots anytime," he says. "You think you can, but you try and there just aren't any. You have to buy them up whenever you see them."

Smith finds himself adding a little bit of heat and spice and flair wherever he can, by bolstering the legacy of the restaurant he helms (his predecessor, Bill Neal, opened Crook's in 1982) with influences from his kitchen crew, mostly immigrants from Mexico, whom he is quick to credit. When he accepted an America's Classics James Beard Award on behalf of the restaurant in 2011, Smith drew a good deal of attention for giving half of his acceptance speech in Spanish. It didn't occur to him to do otherwise.

RELATED Chef Vivian Howard Exalts the Cooking of Carolina "

In the 1980s and 90s, economic pattern brought a large immigrant population to the South. "We have half a million Mexicans in North Carolina now, which I think is a good thing, I'd like to state. So my kitchen filled up with Mexican guys. They'd cook for themselves, make lunch, and I thought, 'God, this is great!' And people now crave spicier food."

The embrace of new global and cultural influences is reflected in the Crook's menu, and also, Smith believes, in the South as a whole. As a gay man working in macho restaurant kitchens, it helped that he was raised to be self-confident—and that confidence manifests in his food and the loyalty he inspires in his team, many of whom have been with him for years. "When I would run up against stuff, I just refused to take it. I didn't start fights or anything, but I didn't let it get me down," he says. "Once you let it be known you're not taking any crap, most people let you alone. Now I dare anybody to say anything. I refused to let it be a deal."

It also helps that he's a damn good cook who is excited to have a part in writing the next chapter of Southern cooking, running a restaurant where shrimp 'n' grits and turnip greens soup are served alongside dishes like pozole and jalapeño-cheddar hush puppies. "It's seen as a cultural record now. Food is the best one. People aren't ashamed of it any more. There's a really wide acceptance of almost everything now. Chitlins, things like that. We're proud of it," Smith says.

"Here, try this; it's what my grandma used to do. It's seen as valid. You have to admit, Southern food is always pretty good. We don't make bad food."