Your Ultimate Sherry Wine Cheat Sheet

Sherry wine is one of the most exciting wine categories. It is the same drink consumers have enjoyed for hundreds of years. However, availability, price, and education have made sherry one of today's most versatile libations. It's delicious served solo, pairs well with food, and is a spicy, nutty base for imaginative cocktails.

Sherry is made from Palomino, Pedro Ximénez, and Moscatel, all white grape varieties. However, the colors range from pale golden yellow to amber to deep espresso. The styles vary from bone dry and best-served ice cold to syrupy sweet, perfect at the end of a meal in place of dessert. Sherry is quintessentially Spanish, relatively inexpensive, with quality options for around $20, and ideal for your next Spanish tapas feast.

Still, sherry production can be confusing. So we're here to answer all your sherry questions, including what it is, when to drink it, and how it tastes. Welcome to the delicious world of sherry.

What is sherry?

Historically, sherry is a fortified wine from D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry in Spain's arid Andalucía. It is crafted by fortifying a base wine after fermentation with a high-alcohol neutral spirit, increasing the alcohol percentage from around 12% to 15-22% alcohol by volume (ABV).

Lying within the Cadiz province, D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry spans across Spain's southern coast to the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the River Guadalquivir to the north, and Spain's flat lands to the east. It is the country's first Denominación de Origen (D.O.), established in 1933, noting recognition for quality winemaking. Within D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry, the distinction is for its sherry wines.

However, the region produced quality wines for hundreds of years before becoming a D.O. In 1100 B.C., the Phoenicians brought vines to the area.

The first rules to govern the production of sherry occurred in 1483. Sherry was the first wine to sail around the world when Magellan carried 253 butts (oak barrels) of Jerez wine on his voyage in 1519 to find a western passage to Southeast Asia. The wine's fortification ensured spoilage was curtailed on ships sailing from Andalucía's ports of Sanlúcar and Cadiz to countries like England and new world explorations.

Why is it called Jerez-Xérès-Sherry?

The Denominación de Origen notes the name in three languages on every bottle of sherry wine. Jerez is the shortened name for the town Jerez de la Frontera. Its meaning "of the frontier" refers to Jerez being the border between Christianity and Islam.

The Muslim Moors had ruled the Iberian Peninsula from the eighth to the mid-13th Century, calling the city Sherish. Though the Koran forbids alcohol consumption, the Moors maintained vineyards for wine exportation. During this time, the Moors introduced distillation methods, paving the way for fortified wine production.

In 1264, the Christians conquered the Moors, and the name became Jerez de la Frontera. However, the English used the Moorish name sherry as they had been importing the product for years by that time. Records show that in the 12th Century, the Moors and England began trading wool for sherry.

Sherry can attribute its success to escalating exportation in the mid-14th Century among the English, French, and Flemish, particularly with England. Xérès is French. Using three names symbolizes the importance of trade in the region.

It also ensured the sherry's authenticity. Only wines following the regulations of the region's governing body, the Consejo Regulador, can be called D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry.

The soils define sherry's character

The essence of a wine is a representation of the terroir. Terroir refers to the grapes' growing environment, including sunlight, wind, and rain. In the production of sherry, the soils play an integral part in the palomino fruit's character and survival, particularly the white albariza soils of Jerez.

Oxidative palomino has low acidity and lacks character when made into dry white wine. However, it's perfect for sherry. Palomino's neutral flavor can easily absorb the mineral-rich calcium carbonate character in the chalky-clay limestone soils.

With a chalky white color and composition, the albariza captures and holds water from the rainy season to sustain fruit during the dry growing season. As irrigation is forbidden in sherry production, the soil's ability to retain moisture is crucial. The albariza stores rainwater deep underground as the upper layer forms a sunbaked crust, preventing evaporation. A vine's roots thrive underneath the crust, receiving nutrients until harvest.

In D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry, palomino accounts for 98% of the grape plantings. The vineyard area, or pago, with the best albariza is known as Jerez Superior and is home to 80% of Spain's sherry vineyards.

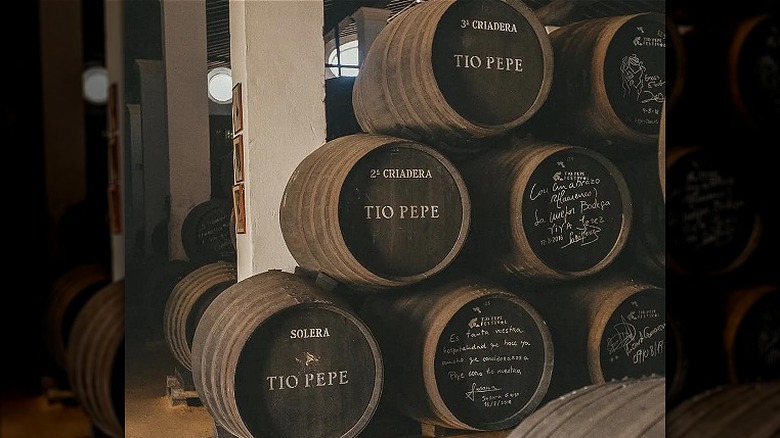

The solera system of aging

All sherry aging occurs using the criadera and solera systems. The criadera is a row of butts aging sherry. A winery can have numerous criaderas, each representing a different harvest. The solera system is the total criadera consisting of several rows of barrels. The method removes the wine from the oldest row of criadera, the solera. Winemakers will sell this wine.

After the extraction, the wine from the second-oldest row will replace the wine removed from the oldest criadera, the third-oldest row will replace that wine, and so on. The procedure creates a house style.

These extractions are called saca, which could be where the old English name sherry sac originated. The saca occurs several times a year. To ensure consistency, winemakers can remove at most one-third of the wine. This fractional blending process creates a constant average age of the wine.

As the solera is never fully emptied, a small portion of wine from the year of the solera's establishment will always remain. Osborne has one of the oldest solera systems in Spain, with the Capuchino solera established in 1790. Capuchino is a V.O.R.S. or very old rare sherry, indicating an average solera age over 30 years. V.O.S., very old sherry, has an average age of over 20 years.

There are instances of a winery producing vintage sherry. However, this is rare.

Sherry ages within the Marco de Jerez

Historically, sherry had to be aged inside the area known as the sherry triangle, made up of three cities, including Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Beginning in October 2022, regulations changed to include the six other cities of the production zone known as the Marco de Jerez. Combing the production and aging areas allows all zone producers to age and label their fortified wine sherry.

The area is ideal for sherry production due to the natural elements of the terroir. The albariza soils are one element. The region also enjoys 300 days of sunshine and 600 liters per square meter of rain annually, and the influence of two winds, the hot Mediterranean-influenced Levante and the cool, humid, Atlantic-influenced Poniente.

The zone's Cathedral-like wineries have thick walls, high ceilings, and clay and gravel floors known as albero. The structures ensure proper aging. Hot air rises to the winery rafters, keeping lower levels cool. The walls keep temperatures consistent throughout the day. Albero floors receive a sprinkling of water, creating humidity that limits the aging wine's evaporation.

Biological sherries have yeasty flor

Sherry is either biological or oxidative. The finest, freshest, driest style ages biologically under a layer of yeast known as flor.

Made from palomino fruit, the two main types are fino and manzanilla, with the latter coming from the coastal town of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. The style uses only the first run and the first pressed juice to ensure a refined, delicate character.

After grapes are crushed and fermented, biological sherries are fortified to 15%-15.5% A.B.V. and placed in 600-liter butts filled almost full. The grand size of the barrel is vital because producers want to limit the oak's influence. As the wine settles, native yeasts in the wine and winery come in contact with oxygen found in the barrel, forming the flor. Flor protects the wine from oxidation. It survives by consuming alcohol, glycerine, and oxygen, constantly changing the fino's aromas and flavors.

As the wine moves through the solera system, the thick layer of flor continues to thrive by feeding on new nutrient-packed wine. The flor is healthiest when the wine is young, dissipating over time. By law, fino must have an average age of two years.

Amontillado sherry benefits from biological and oxidative aging. The wine begins with a fermentation of 15%, allowing the growth of flor. It then transitions to oxidative when flor naturally or intentionally dissipates, exposing the fino to oxygen. It's then fortified to 17% A.B.V., aging with direct oxygen contact.

Oloroso ages oxidatively

With a more robust, structured style, oloroso sherries are generally produced from the second pressing of the palomino fruit. After fermentation, the palomino base wine is fortified to 17% ABV. With an alcohol level this high, the flor can not grow as it can not live at this ABV.

Like a fino, winemakers fill the butts four-fifths of the way complete. As the flor is absent, the wine comes in contact with oxygen throughout the aging process as it moves through the solera system.

Over time a percentage of wine evaporates through the barrel's walls, sometimes up to five percent annually. This evaporation concentrates the wine and creates a smooth, rich, viscous palate and deep mahogany color while increasing the alcohol level to a maximum of 22%.

In today's solera system, the biological sherries will age on the bottom row of the criadera, which is cool and humid. Oxidative sherries age on the top tiers, which are warmer, encouraging evaporation.

What does dry sherry taste like?

With a pale golden color, fino and manzanilla have aromas of yeasty baked bread and soft herbs leading to bitter citrus, almond, green apple, and olive flavors. Both have punchy acidity and a salty character. However, manzanilla is much stronger due to the influence of the Guadalquivir River. Both are highly delicate and refined.

As amontillado contains biological and oxidative characteristics, the amber-hued sherry leads with layers of roasted hazelnut, almond, tobacco, and dried herbs. Oloroso sherries are the richest and most complex, with notes of dried fruits, exotic spices, walnuts, and toffee while remaining dry. Both oxidative styles have a wonderful element of umami, making them delicious with food.

Wineries can also bottle sherry "en rama." By using little filtration, the en rama sherry will have a deeper color and a richer, more pronounced flavor.

Palo cortado is an unexpected gift

Palo cortado is a wonderfully rare style of dry sherry with the literal meaning of cut stick based on the winemaker's barrel designation. It is similar to an amontillado, beginning with biological aging and then transitioning to oxidative. However, unlike amontillado, palo cortado has the richness and body of an oloroso while maintaining a fresh, elegant character of wine made from the first pressing of the fruit.

In the past, the creation of this type of sherry was unexplainable, considered a unique gift from the winemaking gods. Today winemakers can regulate their production by fortifying first press juice aged for a short time under flor to 17%.

Palo cortado is often a winery's most prized selection and is usually expensive. The wine's aromas are concentrated and complex, revealing dried orange peel, tobacco, and spice. It has flavors of roasted nuts, balsamic, and dried red fruits, with fresh acidity lingering throughout.

Sherry can be naturally sweet

Two styles of sweet sherry are naturally sweet and blended to become sweet. The former includes wines made with Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel. Their vineyard plantings cover about 5% of the total in the sherry region.

Pedro Ximénez is one of the world's sweetest wines due to the "asoleo" process. The process sun-dries well-ripened grapes on mats concentrating the fruit's flavors, sugars, and complexity. Dried grapes are pressed and fortified to 17% after fermentation and age oxidatively. The resulting wine has flavors of dried figs, raisins, espresso, and dark chocolate, mixing with freshness.

Slightly lighter, with more citrus and floral notes, Moscatel can also raisin in the asoleo process or be fortified after traditional fermentation before aging oxidatively. A highly aromatic variety, Moscatel opens with white flowers and honeysuckle that lead to sweet candied citrus and caramel flavors. Moscatel generally grows in sandy soils known as arenas by the sea, giving the wines a hint of salinity.

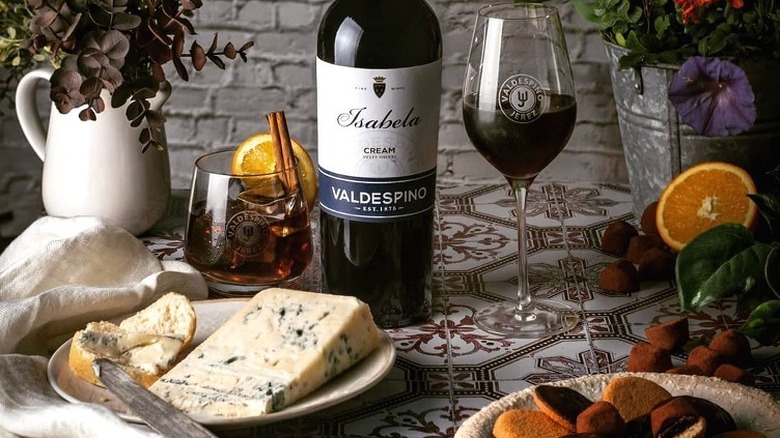

Cream sherry is sweet and savory

Besides naturally sweet sherries, blended sherries use fino, amontillado, and oloroso. There are three styles, pale cream, medium, and cream, which the Spanish call Vinos Generosos de Licor. However, outside Spain, the category is referred to as cream.

When making a cream sherry, dry sherries are mixed with naturally sweet sherries or by using a sweetened rectified grape must. The lightest style is pale cream made from fino sherries; medium is made from amontillado and is half sweet; blending oloroso with Pedro Ximénez creates the heavily sweetened cream sherry with layers of nutty, syrupy flavors.

The blending can occur before bottling or after several years of aging to integrate the flavors. The alcohol levels range from 15.5-22% ABV.

Sherry is perfect before, during, and after dinner

Sherry offers so many styles that it is perfect throughout the evening. With its light body, lower alcohol, and a hint of salinity, fino is ideal as an aperitif awakening the palate while triggering the salivary glands. Fino is an excellent pairing for snacking, enjoyed with potato chips, olives, Marcona almonds, and seafood like frito misto or a tuna poke bowl. The style can also enhance two of the most challenging foods to pair wine with, asparagus and artichokes.

Moving on to main courses, the nutty character of amontillado and dry yet fruit and spice-filled oloroso pair with savory cuisine. Enjoy an amontillado with smoked duck, pate, or rich meats and cheeses on a charcuterie board before moving on to a spicy oloroso paired with low and slow barbecue or any game meat.

Cream sherries pair with fruit-based salads or desserts, foie gras, strong cheese, or spicy Thai red curry. With high sugar content and syrupy texture, Pedro Ximénez is the ultimate dessert wine, whether you drink it or drizzle it over vanilla dulce de leche.

What is the best way to drink sherry?

Sherry is best served chilled. Serve fino around 44-48º Fahrenheit, and the remaining served in the mid-50ºs.

It is often served in a classic short-stemmed sherry glass with a tulip shape. This type of wine glass, known as a sherry schooner, can be used for all sherry. However, a traditional white wine glass is also an option, particularly when sipping a delicate biological sherry.

The shape of the wine glass allows the lower alcohol fino to open in the bowl while concentrating the aromas around the lip. It allows a complete sensory experience, enjoying its color, aromas, viscosity, and flavor. Fill the glasses only partially, giving the wine room to bloom, releasing the aromas.

Most dry and sweet sherries are best served neat. However, cream sherry is best enjoyed over ice, often with a twist of orange to enhance the fruit flavors.

Sherry is a good base for cocktails

From simply pouring a cream sherry over ice with a twist to imaginative combinations, sherry is a lower alcohol base for cocktails. Most spirits deliver a minimum of 30 or 40% ABV; amontillado or oloroso is generally half of that.

There are historical options, like the sherry cobbler, the cocktail made famous by Charles Dickens. The cocktail combines a few ounces of dry sherry, like amontillado, with sugar and fresh citrus slices. Shake and pour over ice with berries and oranges for garnish.

Or, give a rebujito a try to help quench your thirst on a hot day. Inspired by the sherry cobbler, the cocktail combines fino with lemon, sparkling water, and mint, shaken and poured over ice. Or, take a shortcut by combining the fino with citrus soda, like Sprite, for a straightforward Spanish cocktail.

Should you open or store sherry?

When deciding when to open a bottle of sherry, the general rule is when the wine is released. It's gone through the aging process before bottling. This understanding is especially true in biological sherries as their freshness and zesty bite are best appreciated when young, generally within the first year or two. Waiting too long could result in the wine tasting flat, lacking the zip that makes them so delicious.

Aging oxidative sherries in the bottle can help mellow the wine. Still, it is still best to enjoy within five years of release.

Like all wine, the best place for storing sherry is in a cool, dark space free from vibration. However, unlike other wines, sherry bottles should be stored upright, ensuring the higher-alcohol wine will not dry the cork.

How long does an open bottle of sherry last?

Depending on the style of sherry, once you have opened a bottle, you have anywhere from a week to a few months to enjoy it. The key to preservation is proper storage. You will want to ensure the bottle has been properly sealed with a strong wine stopper to ensure air does not permeate the beverage. The wine will then need to be stored upright inside a refrigerator.

For fino and manzanilla sherries, you'll have about a week to finish the bottle before it spoils. Amontillados have slightly longer, remaining flavorful for up to three weeks. Oloroso and cream sherries will last about four to six weeks. Naturally sweet styles of sherry can last up to two months before tasting off.

With any of the wines, the longer they are open, the more at risk of exposure to oxygen and light. Oxidation can damage the flavor, causing the wine to go off. It won't be harmful to drink if you keep a bottle longer than recommended. However, it likely won't taste pleasant.

Sherry continues to evolve

In 2021, the Consejo Regulador passed new regulations that continue to change sherry's landscape, altering traditional concepts while keeping the category relevant. In addition to opening the aging zone to include the Marco de Jerez, fortification, grape varieties, packaging, and labeling processes have changed.

As of October 2022, sherry no longer has to be fortified. As temperatures rise, grapes can naturally ripen to 15% ABV, the minimum the D.O. regulations allow. If the alcohol level reaches 15%, it can become sherry. We'll likely only see non-fortification in biological wines as the oxidative wines must achieve 17% ABV. New grape varieties, including ancient vejeriego and beba, are also permitted. Winemakers can also package sherry bag-in-box (i.e., boxed wine).

Sherry vs. port

Spain's sherry and Portugal's port wines share several similarities. They are fortified wines made in neighboring European countries that invented the solera system. Both can age extensively in a barrel or bottle and have similar alcohol by volume ranging from 15-16% to 21-22%.

And, much of both products' success can be attributed to the English. Still, sherry was in favor for hundreds of years before port.

There are differences between sherry and port. Port is a sweet wine; sherry can be dry or sweet. Most port wines come from a blend of red Portuguese grapes. Sherry uses only white grape varieties.

Port is fortified during fermentation, resulting in a sweet red wine. Dry sherry is fortified after fermentation with a small amount of a high alcohol-neutral wine spirit. The neutrality ensures the liquor will only increase the alcohol percentage, not change the sherry's character or flavor.

Are cooking sherry and drinking sherry the same?

There is a saying regarding cooking with wine, noting that you shouldn't cook with wine you wouldn't drink. Technically speaking, if the cooking sherry is from Jerez, it is the same as drinking sherry. However, we don't recommend drinking cooking sherry.

Cooking sherry begins with fruit fermented into wine and then fortified with brandy to around 16% alcohol, similar to drinking sherry. The wine then receives a hearty dose of salt and other preservatives to guarantee a long shelf life.

Sherry-cooking wine intends to impart flavor for upwards of a year after opening when refrigerated, much longer than a typical opened bottle of sherry. However, you should reconsider buying cooking wine as the sodium is high and lacks authentic flavor. Instead, try an amontillado from Gonzalez Byass or Lustau. It will add nuttiness to dishes like shrimp bisque or osso bucco while providing you with a delicious aperitif.