13 Myths About GMO Food, Debunked

When you hear the phrase "genetically modified food" (GMO), what picture comes to mind? Are there scientists peering over a petri dish? Or is it the grotesque image of a strawberry photoshopped onto a salmon with the words "Ban GMO" on the bottom? Certainly, genetically modified food has earned its fair share of controversy and misrepresentation over the years, but that doesn't mean that it is something you should be fearful of.

With a background in food systems and food sciences, I've come across GMOs and the subsequent controversy many times over the years. Now, I'm even faced with bigger questions as a consumer, as I'm forced to choose between bioengineered and non-GMO foods at the grocery store. In a effort to better inform you about the realities of GMOs, I've collected a long list of the common queries people have about this technology and its application as well as information that either refutes or supports these common objections. I should note that my effort here is not to sway you to buy or not buy GMO food but rather to dispel some of the many myths about this technology.

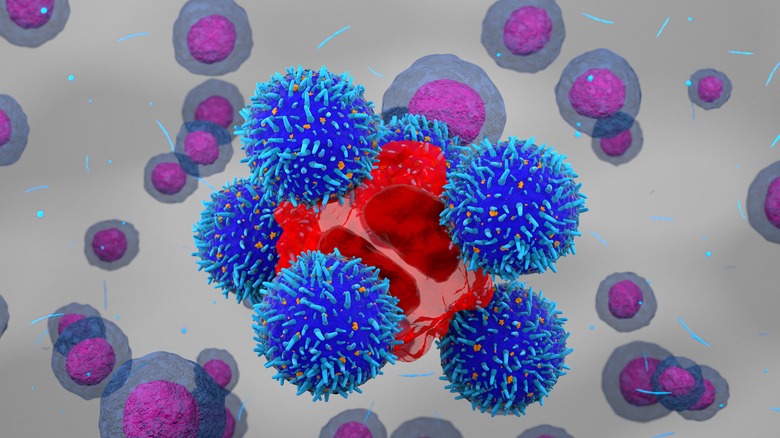

GMOs allow scientists to make 'Franken-food'

The phrase "genetic modification" may make you think of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" and its concurrent imagery of monsters stuck together with tape and a variety of body parts. However, the reality of GMOs is actually far from this.

First, I have to explain what, exactly, a genetically modified organism is. GMOs are living things (including plants, animals, and bacteria) that have purposely had their fundamental genetic code altered. For example, scientists can insert certain genes from living things into other living things where they would not normally appear. One example of this is the rainbow papaya, which was developed during the deadly 1940s ringspot outbreak in Hawaii. A team of scientists inserted a part of the virus' genetic code into the papaya so the plant would be resistant to it. The virus' genetic information wouldn't intermingle with the papaya's unless humans inserted it.

Scientists can also turn certain gene expressions on or off to create a desired effect. For example, Del Monte created the rosé pineapple by altering an enzyme in the pineapple plant to ensure that the fruit stayed pink rather than turning its normal yellow color. This also made the fruit taste sweeter. PinkGlow pineapples, as they're otherwise called, look "normal" from the outside, aside from pattern changes on the exterior, so chances are that you wouldn't know you were eating a GMO pineapple until you sliced into it. The gene alteration often has very minimal visual effects (besides for the obvious change of color for plants like the rosé pineapple). It's far from the Franken-food that some people think it is.

Genetic modification is just an extension of artificial selection

There are several different types of plant and livestock breeding — one of which is the process of artificial selection. Darwin proposed this concept in the 1860s, and it's application has revolutionized how people selectively breed animals and plants. Artificial selection is a process in which humans control which animals or plants breed to express certain desirable traits. For example, if you're looking to produce a chicken with a greater proportion of breast meat, you would breed chickens that share that desirable trait. Eventually, after successive generations, you'll get the desired trait that you're looking for.

But don't you "artificially" select genes when you perform genetic modification? Technically, both have humans as the impetus, and both can create a wanted outcome. However, genetic modification allows scientists to make changes at the molecular level without having to work within the confines of genetic variation. For example, if the chickens you're breeding for a higher quantity of breast meat carry the risk for developing a certain cancer, in an artificial selection scenario, there would be no way to bypass that cancer risk just to breed for a higher quantity of breast meat. Still, if you can just insert or turn on a gene for a higher ratio of breast meat, you can solve all your problems.

The precision of genetic modification also allows scientists to insert DNA into organisms that wouldn't otherwise appear in nature, like when scientists transferred genetic code from the daffodil and a soil bacteria into rice to make golden rice, a type of rice with a higher beta-carotene content than other varieties. You could selectively breed rice for eons, but there's no telling if you could produce a variety that's high enough in beta-carotene to pass that trait down to successive generations via artificial selection.

Genetic modification is a new technology

Genetic engineering might be an older concept than you'd think. In 1973, biochemists Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen were the first to utilize genetic engineering when they inserted one bacterium's DNA into another. However, it took another 10 years before the first Food and Drug Administration-approved GMO product was released to the market: genetically-modified insulin. Once GMOs came to the marketplace, there was a flurry of activity and decision-making to decide how to regulate them.

In 1994, consumers saw the first GMO produce — the Flavr Savr tomato. This was a revolutionary technology that would allow a particular type of tomato to stay firm even after harvesting. Its release created a cascade of new GMO produce, including sugar beets, cotton, canola, and potatoes, but it wasn't until 2015 that the FDA cleared the first genetically-engineered animal, a salmon. This fish grows twice as fast as non-GMO Atlantic salmon and was in the research, development, and approval process for nearly 20 years.

You can get an allergic reaction from eating GMOs

Anaphylaxis is the a serious health threat for some people, so the question of if eating a genetically modified organism with genes from a trigger species can cause an allergic reaction is valid. However, there have been no reported cases of allergic reactions tied directly to GMO foods. Moreover, there is no evidence that GMO foods cause more allergic reactions than regular food.

There are eight major allergens found in the food system: gluten, soy, dairy, peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish (the most common cause of food allergy), sesame seeds, and eggs. Some of these products, like soy, are genetically modified already. Genetically-modified food does not become less of an allergy trigger after it's genetically modified, so someone who is allergic to soy will still be allergic to GMO-soy — and they will need to read the product's label and check for the addition of the ingredient, whether it's genetically modified or not, to prevent an allergic reaction.

You wouldn't know if the food you eat has GMOs in it

The National Bioengineered Food Standard implemented by the FDA stated that by 2022, all food manufactures, importers, and some retailers must label any food sold in the U.S. that contains a GMO with text that reads "bioengineered food," directions on the label for how to find the bioengineered food disclosure, or the bioengineered food seal. The Standard defines a GMO as having "detectable genetic material that has been modified through certain lab techniques and cannot be created through conventional breeding or found in nature" (via the Food and Drug Administration).

This legislation, which was signed by President Obama in 2016, is a big change from the 1990s when GMO foods were not required to be labeled. Some third-party certifiers have also taken it upon themselves to label non-GMO food — the most prominent of which is the Non-GMO Project. However, Non-GMO Project labeling is voluntary, meaning that companies have to pay to have it on their packaging and adhere to a certain standards and protocols for food processing to ensure that no GMO contaminants enter that food. If anything, it's a marketing gimmick used by producers; The Project even reports that sales increase 20% when companies use "active promotion" of the label (via the Non-GMO Project). Some brands, including Trader Joe's, have also voluntarily chosen to not sell products made with GMO ingredients.

GMOs are bad for the environment

Whether GMOs are bad for the environment or not really depends on who you ask — and there is research that supports both sides of the argument. For example, Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis, a bacterium) corn can produce higher yields than corn that's been decimated by agricultural pests. This demonstrates an increase of efficiency and better use of resources, as farms have to apply fewer pesticides to the GMO corn. According to research from the Entomological Society of America, the use of insecticides on Bt cotton and corn declined by 80% between 1996 and 2017. Another study published in the Journal of GM Crops and Food indicates that the use of Bt and herbicide-resistant genetic engineering (as with Roundup Ready plants) also indirectly decreased the carbon footprint via cuts in fuel use and tillage. This change is the carbon dioxide equivalent of pulling 11.9 million cars from the roads.

However, other research suggests that the use of this technology has actually caused the number of herbicide-resistant crops to increase, causing farmers to purchase more herbicides to tackle the issue. The use of these herbicides has downwind effects that can harm soil and cause water pollution.

Eating GMOs is not good for you

This is one of the most common myths associated with GMO foods, and it is not at all true. GMO crops are just as nutritious and healthy as non-GMO crops. Moreover, there are even some GMOs that may be healthier than their non-GMO counterparts, with weed killer being more of a concern. For one, there are GMO soybeans. While, nutritionally speaking, there may not be a large difference between the two, there is a difference when it comes to insulin resistance. Research shared by the University of California Riverside suggests that GM soybean oil does not cause insulin resistance like non-GM soybean oil can. This is likely because GM soybean oil has a higher LDL cholesterol content, similar to that of olive oil, rather than the higher trans-fat content traditionally found in soybean oil. An animal study also showed that mice given GM soybean oil gained less fatty tissue over time than those that were given regular soybean oil. However, more research will need to be done before this can be applied to humans.

Another pertinent example of improved nutritional outcomes is golden rice. This rice was infused with genetic material from the daffodil plant and a soil bacteria. The result was a beta-carotene-rich (a precursor to vitamin A) rice that can substantially reduce vitamin A deficiencies in populations heavily dependent on the grain as a source of food. Golden rice offers 30 to 50% of the recommended daily intake of vitamin A.

Genes from GMO plants will spread to other plants

Another frequently highlighted environmental risk associated with genetic modification is the spread of GMO seeds and genetic material to non-GMO plants. This "contamination" can be the result of several different factors. For one, the pollen from a GMO plant can reach a non-GMO field, or the seeds can get mixed together accidentally — like if a farmer used a shared seed spreader. Not all GMOs have this wandering pollen issue (for example, soybeans are self-pollinated). However, farmers have developed some impressive measures to combat the issue, including avoiding planting GMO and non-GMO plants next to one another, creating barriers with "volunteer" crops that they don't intend to sell, or altering their planting schedule to time the pollen drift.

It's important to note that if an animal, like a cow or a chicken, eats genetically modified corn or soy, it will not inherently become a genetically modified organism. And if you eat a genetically modified piece of corn, you will not turn into a GMO either.

Organic food does not contain GMOs

Like genetically modified food, organic food comes with its own set of controversies. Regardless, consumers looking to purchase non-GMO food can opt for organic food. Currently, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the regulatory body associated with defining the organic standard, prohibits the use of GMO ingredients in any USDA organic-labeled product. That also means that livestock cannot consume any food that contains GMO ingredients such as alfalfa, soybeans, or corn.

Farms that produce organic-certified products and GMO foods must show that the two are separate and that cross-contamination does not occur. Moreover, these operations are often subject to testing to ensure that their organic-certified food does not contain any trace of GMOs.

GMOs are released to the market without adequate testing

The idea that the FDA releases GMO products to the market without doing adequate testing on them almost crosses the line of being a conspiracy theory. The fact is that the processes regulating the production and use of genetic engineering is very restrictive. Companies have to consult with the FDA in the development of their genetically modified food product, submit food safety information showing any potential human health risks, then publish their consultation findings on the FDA's website. As a consumer, you can log into the final biotechnology consultation database and see the name, application, and relevant information about a proposed GMO food. The process from development to release can take several years, and for some GMOs, this may be the difference between making it to the market and not getting out of the lab.

It isn't just the FDA that collaborates in some regulatory capacity; The USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) regulates potential risk of diseases, while the Environmental Protection Agency examines the use and risk of pesticides as they pertain to the GMO. This approach ensures that numerous agencies are involved in the risk assessment and approval of bioengineered foods.

Much of the food we eat is genetically modified

Based on the amount of talk around GMOs, you would think that almost everything we eat would fall under this umbrella. However, very few crops in the United States are genetically modified.

Nevertheless, the amount of GMOs consumed is massive because of the concentration of foods such as soy, corn, and meat (animals that feed on GMO corn and soy) in the American diet. As of 2020, 94% of all the soybeans, 92% of all the corn, and 96% of all the cotton planted in the United States is genetically modified. Moreover, 95% of the meat that we eat in the United States is fed with GMO crops. Likewise, products manufactured with these ingredients are considered made with bioengineered ingredients. Think for a second about the number of products that you eat that contain corn-derivatives. Cornstarch? Corn syrup? Corn oil? Dextrose? All of these wouldn't be possible without (genetically modified) corn. Oh, and don't get me started about GMO sugar beets!

Besides these commonly-eaten foods, there are also some fruits and vegetables that are genetically modified, including papayas, potatoes, apples, and summer squash. Still, not every fresh food in the produce section of your local grocery store has been genetically modified.

GMO food may cause cancer

As you can probably assume, if scientific testing is rigorous enough to show any potential human health risks of eating GMO food, it can probably detect a correlation between eating GMOs and cancer. Currently, there is no research to suggest that eating GMOs increases the risk of developing cancers. Moreover, scientists promote the consumption of fruit and vegetables (regardless of if they contain GMOs or not) as a way to potentially reduce the risk of the disease. And if GMO food is more affordable than non-GMO food (thanks to increased yields), it's reasonable to suspect that the cost differential may cause more people to eat fruits and vegetables.

So, where did this GMO-cancer theory originate? There were some reports that the process of mingling genetic sequences (like adding Bt proteins to a plant) resulted in stress-driven changes and abnormal growth. However, this occurred in the confines of a petri dish, which means it can't be generalized to the whole population. And it's a bit of a stretch to postulate that changes in a plant would cause abnormal cell growth (cancer). Also, a study was circulated that theorized glyphosate, the herbicide that some GM crops are resistant to, was tied to breast cancer was completed in a laboratory with samples that already had cancer. Ultimately, there's no way of proving a correlation between glyphosate and an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

GMO plants kills honeybees

"Save the bees!" is seemingly plastered on everyone and everything nowadays, but don't let the GMO noise into the picture. There has been no research to conclusively prove that GM crops affect honeybee or monarch butterfly populations. Research collected, conducted, and presented in Advances in Botanical Research shows that herbicide-tolerant plants (like Roundup Ready soybeans) do not affect the survival of honeybee populations in both laboratory and field trials. And if GM crops use less insecticides, that might actually be doing something to help the pollinator population.

While some folks point to neonics, an class of insecticides that carry risk to honeybees and other pollinators, as being a culprit for declining bee populations over the past few decades, scientists are quick to point out that this class of chemicals is used on both GMO plants and non-GMO plants. The causes of colony collapse disorder are much more complicated than that and cannot be directly correlated to GMOs.